To the Muslims, the Arabic word, ‘Mohajir’ has a religious reference and value. The word acquires significance, because the Prophet (PBUH) migrated from Makkah to Madinah. The Muslims of Makkah emigrated in large numbers.

Not all those who move from one place to another qualify to be called Mohajirs. Nomads cannot be considered Mohajirs, because they move out of their own volition. Mohajirs are those who because of one reason or the other are persecuted and hence exercise the choice to leave their ancestral lands, in search of safety.

The people of Makkah emigrated because of torture and persecution. Madinah was safe for the people from Makkah as the Ansars welcomed them with grace. Culturally and linguistically, the people of Madinah were not significantly different from the Meccans, so the assimilation between the two was smooth and easy. Hence, with this historical background, a certain nobility is attached to the word Mohajir.

Recently, the Mohajir Culture Day was celebrated in Sindh. First celebrated in December 2020, it was a good move, which was possibly initiated more out of political compulsion than anything else, and may have had very little to do with culture.

In the words of T.S. Elliot, “Culture is the one thing that we cannot deliberately aim at. It is the product of a variety of more or less harmonious activities, each pursued for its own sake.” Man, at worse, has base animalistic tendencies and it is only through culture that he is able to rise over and resist the beast and carnal self in him.

Normally, invaders consider those whom they subjugate and vanquish, as less intelligent and inferior to themselves. It is generally believed and presupposed by them that the standards of civil behaviour and the refinement of their own culture gives them an edge over local practices.

Most Muslims of the South Asian subcontinent are, in more than one way, descendants of the practices of the mighty Mughal Empire that spread over 3.2 million sq-km. The plundered wealth constituted their treasure, while the Mughal opulence and sophistication spread its influence over all the inhabitants from Kashmir to the Deccan plateau. The ceremonies, etiquette, music, poetry and exquisitely executed paintings and objects of the imperial court fused together to create a distinctive aristocratic high culture.

Hermann Hesse, the German-Swiss poet, novelist and painter had remarked the following painful truth: “Human life is reduced to real suffering, to hell, only when two ages, two cultures and religions overlap.” Culture finds manifestation in the manner we live which has usually a connection with the past. The massive influence upon the subcontinent of the culture of Central Asian States, the Arab world and Turkey is evident. The Turkish influence travelled southwards to the extent that even today, many Muslims of Hyderabad Deccan adorn the Rumi Topi (Rumi, the Sufi Saint’s cap) as part of their formal dressing.

“Educated people do indeed speak the same languages; cultivated ones need not speak at all.” (The Cart and The Horse by Louis Kronenberger). Learning, education, and training when conjoined with cultural manners and a general sense of civility contribute to create and produce the most exquisite and remarkable products for a culture to subsist.

The development and sustainability of culture lies in the impact it has upon elements that prompt the emergence of character. But if it fails the test of not ennobling and strengthening behaviour, then it is of no use. Culture must be for goodness and not for display as a thing of beauty.

In a 1964 essay, The Culture Consumer, Alvin Toffler made the following observation on the dissemination of cultural values and standards over the time scale of human history. He called it “The Law of Raspberry Jam ― the wider any culture is spread, the thinner it gets.”

Culture by its nature is both hard and malleable. The universal foundations of truth and human goodness as pillars of culture cannot be allowed to remain in any state of fluidity. There can be no room for either disbanding or refashioning these cornerstones, hence these are entrenched firmly.

Culture has the ability to absorb, the goodness and reconcilable elements of other cultures. Regardless of religious inclinations, it is undeniable that the hugely popular rasm-e-mehndi or henna ceremony in our local wedding functions is a direct incorporation of Hindustani culture, not to be confused with Hindu culture.

Amir Khusro was so deeply influenced and inspired by the cultural practices of local citizenry of Delhi, that over a few centuries it got enshrined as part of Mughal culture. The culture of the rivers Ganga-Jumna is predominant in the daily lives and practices of the Muslims of Uttar Pradesh (UP).

Culture is not law, it is a heritage, and the way we live and conduct our lives is a reflection of culture. It is commonly said that culture is half way to heaven. The crystallisation of cultural practices go towards making a civilisation. It is an excellent fusion of the present with the past. As English literary critic, Cyril Connolly aptly says, “Neither in countries without a present nor those without a past is culture to be discovered.”

The arrival of spring is celebrated by all cultures, but differently. For the Persians it is Nauroze, for the Chinese it is the lunar New Year and for the natives of Telengana, it is Tilsangraat. All the same, the celebration of the arrival of spring depicts the local flavour of its own heritage and culture.

The litmus test of any culture is not in the size and number of its practitioners, nor in the economy that they generate. Instead, it lies solely in what kind of human beings it produces. To be recognised, culture must the ability to create civil people. According to Arnold Toynbee in an October 1958 issue of Readers Digest, “Civilisation is a movement and not a condition, a voyage and not a harbour.” All cultures have geographical links.

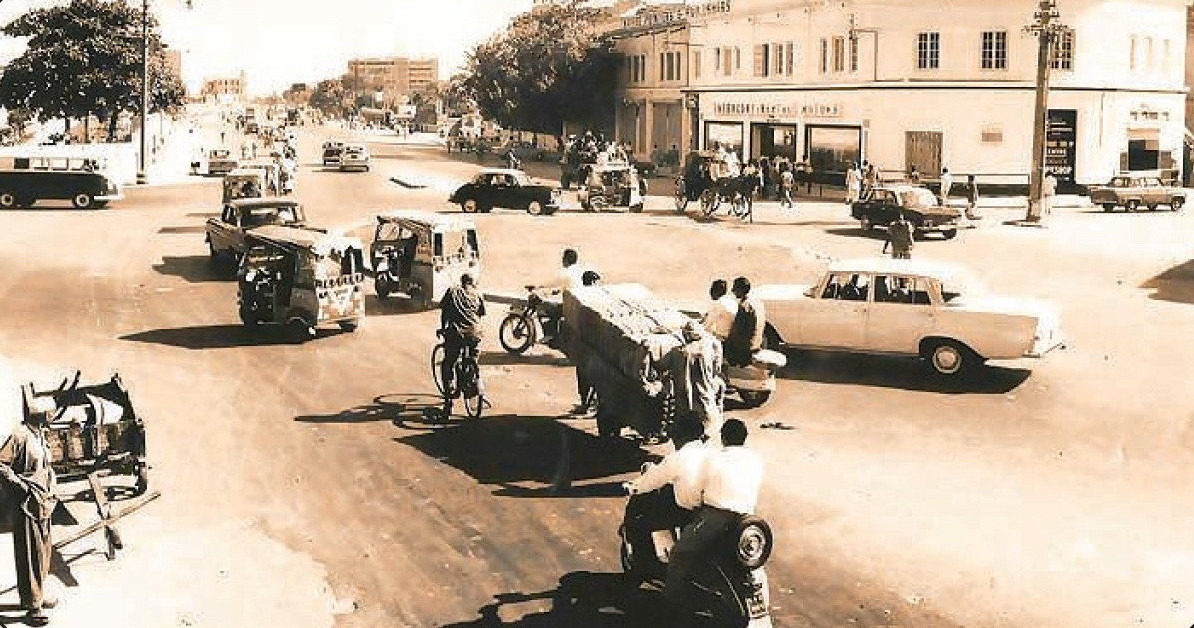

Following partition and independence from the British, human history witnessed a story of great sacrifice when the largest and the bloodiest exodus took place. This was the migration of Indian Muslims to their new homeland that they had fought and struggled for. The enthusiasm and joy of wanting to live in Muslim Pakistan outweighed the considerations of leaving behind ancestral property, relationships of decades and the comforts of what then constituted their previous home. Leaving everything behind, they marched towards the Promised Land, The Land of the Pure, christened as Pakistan.

The cultural mix that existed till the breakup of Pakistan in 1971 was a pot-pourri of people from UP (who considered themselves culturally superior to all others), Rajasthan, Bombay Presidency, East Punjab, the Kokans from south Maharashtra, the Madrasis from Tamil Nadu, the Mysoreans from Karnataka, the Bhopalis of Central Province, and the Gujaratis from Kuchh, Surat and Ahmedabad, etc. The influx into what was then West Pakistan was largely from North and Central India and the provinces of the west, going down South to Hyderabad and Kerala, while the migration to East Pakistan was from West Bengal, Bihar and Orrisa.

The only common denominator between this spaghetti of human kind was their religion of Islam, the only binding factor. Each had their distinct and separate culture, with very few overlaps in practices and manner of living. Even after migration they did not mingle among themselves, let alone with the natives. This attitude is best explained by the existence of Karachi’s Aligarh Society, Hyderabad Colony, Bahadurabad, Dhorajee, Benaras, and Bihar Colony.

The tracing of roots remains a dominant force of humans. Intermarriages between them and local natives was almost a social heresy, so each grew from within with the people from UP marrying others from UP, the Hyderabadis marrying Hyderabadis, the Bangloreans, the Gujratis and the rest also followed the same practice of not mingling.

The migrants from East Punjab settled with ease in West Pakistan’s Punjab province because of linguistic reasons. They mingled with and married into the local population and presently no one can distinguish between them. Similar was the case with people from West Bengal who moved to East Pakistan.

Sadly, the same cannot be said of Mohajirs in Sindh, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. They chose to remain distinct, despite the apparent diversity between themselves. Hence integration did not happen. The only commonality is that they speak Urdu, albeit, with pronounced difference in pronunciation. They are now classified as Urdu-speaking, which is a great negative fallout, since Urdu is their national language.

The sad and traumatic year of 1971 saw the exodus of Biharis from Bangladesh. They arrived and like earlier migrants settled in the urban areas of Sindh. Today, they are part and parcel of the political Mohajir clan, but still quite different. A very dear friend, who sheepishly traces his origins to Patna (Sharif!), gets extremely excited when I exhort his children to marry a foreigner, as in not from Bihar. And that is just one example. The same is true of Hyderabadis, Bhopalis, and the people of UP, etc.

In short, barring the one unique and common feature of Urdu being the language of conversation, culturally there was nothing in common. The Hyderabadis relish their double ka meetha, the Gujratis promote malpoorra, the Biharis flaunt Bihari kababs. So even in the culinary aspect, the differences remain.

Hence, there never was a concept of Mohajir culture, because there isn’t any that existed in the past or even the present. As a political ploy, it is an interestingly entertaining concept.

Amending the words of Thomas Bailey Aldrich, for the purpose of this piece, the culture, if any, of the migrant Karachites and also the original Karachites, for the last seven decades is like the lamb skin in which barbarism masquerades.

“What do you think of modern civilisation?” a journalist asked Gandhi, who replied, “That would be a good idea.” Borrowing his words, if someone asked me about Mohajir culture, I would repeat Gandhi’s reply.

The writer is a senior banker, an author, and contributes regularly to newspapers. He can be reached at azizsirajddin@gmail.com. All information and facts are the sole responsibility of the writer