There is a mystery about buried relics that excites the imagination and conjures up images of lost treasure hordes. Treasure hunters have made discoveries of great value, particularly from the seafloor, and salvaged fascinating artifacts from the wrecks of the Spanish treasure fleets, Chinese junk, and ships of the East India Company returning home with loot from the Indian subcontinent. My quest is for an object that lies buried in the River Chenab for the past 260 years. In monetary terms, its value may only be the price of the copper and bronze of which it was made, but it has significant historical value.

The library of the Joint Staff Headquarters, where I served in 1999, housed a large book collection that previously belonged to the late Syed Akhtar Ahsan, a writer, voracious reader and Syed Babar Ali’s brother-in-law. The collection, which includes books on history and military campaigns, was presented to the library by Ahsan’s family. One of these, authored by Ganda Singh in 1959, was on Ahmad Shah Durrani or Ahmad Shah Abdali, the Afghan Sadozai king who in the 18th century conquered the lands of the River Indus and its tributaries. Abdali is also known as the king who cast a gun called Zamzama.

According to Singh, not one but two guns were cast. A year later, I bought Peter Hopkirk’s Quest for Kim: In Search of Kipling's Great Game. Hopkirk too mentions that the Zamzama ‘… once had a twin. However, this was lost during a river crossing while being dragged back to Kabul by Abdali’s victorious artillery men and today it lies, somewhere at the bottom of the Chenab river, forty miles west of Lahore.’

The mightiest of its time

Weighing 4.5 tons, Zamzama is one of the most magnificent cannons of its time. With a barrel over 14ft long and a bore at its aperture of nine and a half inches, it was forged using copper and bronze utensils collected from the residents of Lahore as jizya, a tax levied on non-Muslim subjects by Muslim rulers. The Zamzama is far superior to the Bhurtpore Cannon cast in 1780, some 25 years after the Zamzama. The latter was captured by the British during the Siege of Bhurtpore [Bharatpur] in 1826, and displayed outside the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, in England. Though the barrel has the same length, it is two tons heavier with only half the caliber of the Zamzama.

The muzzle end of the Zamzama bears Persian inscriptions and a chronogram: “By the order of the Emperor, DuriDurran, Shah Wali Khan Wazir made the gun named Zamzama or the Taker of Strongholds.” The longer inscription eulogises its bulk and invincibility: “From reason I enquire of the year of its manufacture; Struck with terror it replied, ‘Wert thou willing to surrender thine life, I would unfold unto thee the secret.’ I agreed, and it said, laden with innuendo: – ‘What a cannon! ‘Tis a mighty fire dispensing dragon!’. The last line of the longer inscription adds up to 1169 Hijri (1755-56 AD). Four years after being manufactured, the cannons helped Abdali defeat the Marathas in the Third Battle of Panipat, in 1761.

Further research brought to light some conflicting historical accounts. Majid Sheikh in his article “Why Abdali got such a huge Zamzama made” writes that both guns were manufactured by Shah Nazir, a metal smith who worked for the Mughal emperors. Within three months, Nazir completed two massive cannons at a special furnace in Mughalpura, where presently stands the Mughalpura Railway Workshop. After the battle, both guns were taken to Lahore to be fitted into stronger undercarriages for the journey to Kabul. One carriage was ready on time, while the one for the Zamzama was delayed and it was left in Lahore in the care of Khwaja Obaid, the new ‘subedar’ of Lahore.

Since the undercarriage was constructed in a hurry, while being ferried across the Chenab near Wazirabad, it collapsed and fell into the river. Meanwhile, the ordnance depot of Obaid located in the outskirts of Lahore was attacked by the armies of Hari Singh Bhangi and the Zamzama fell into their hands. The new Sikh owners of the cannon renamed it Bhangianwalli Toap or ‘Cannon of the Bhangis’.

But travel writer, Salman Rashid does not mention a second cannon in his article Rites of Passage, posted on his blog site on August 29, 2013. He writes “It was on this ford of Rasulnagar that Abdali, who had murdered and replaced the mad despot Nadir Shah in 1747, was discomfited in the winter of 1752. Encumbered by the mammoth cannon Zamzama, Abdali’s horde desperately tried to effect a crossing of the river and fight the Bhangi Sikhs at the same time but in vain. Paying a heavy toll in life and plunder Abdali’s forces barely made it across the river, leaving the cannon stuck in the sand. The jubilant Bhangis retrieved the gun to place it outside Rasulnagar’s western gate as a trophy of a battle well fought.” Rashid also mentions a gate called Darwaza Tope Wala or ‘Gate of the Cannon’ in Rasulnagar. It is highly unlikely that the cannon could have been retrieved. The barrel alone weighed 4.5 tons and the carriage must have weighed about as much.

A third account by Syed Muhammad Latif in his book Lahore, Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities, published in 1956 reiterates the existence of two cannons, and one being lost in passage over the River Chenab. The Bhangi Sikhs passed the Zamzama on to the Sukerchakia Sardar when he demanded his share of the spoils. It kept changing hands between the Sukerchakias, the Chathas and the Bhangis during tribal feuds. During this period, it was placed at Gujranwala, Gujrat and Rasulnagar. Finally, the recaptured it and took it to Amritsar where it landed in the hands of Maharaja Ranjit Singh when he conquered the city in 1802.

The maharaja used it in five battles but after it failed to fire during the siege of Multan, the cannon was decommissioned and placed in front of the Delhi Gate in Lahore to commemorate the Sikh victory against the Afghans. For HRH, the Duke of Edinburgh’s visit in 1870, the British relocated the cannon to the Mall opposite the new Lahore Museum.

Rudyard Kipling’s novel about the Great Game opens with the scene in which Kim in defiance of municipal orders during the British Raj, sits atop the gun which bore his name ― Kim’s Gun. After Independence, the cannon was beautifully restored and its name reverted to the original.

Contemplating the hunt

These accounts lead to a hypothesis that both the cannons arrived on the banks of the River Chenab. As the Afghans were transporting it to Kabul, the first one either sank into the river or got stuck becoming unrecoverable, and ultimately vanished when the river flooded during the monsoons. There it lies forgotten like the grave of an unknown soldier. The second as recorded by Latif arrived later and landed in Lahore via Amritsar. Can we find it after two and half centuries?

The first step in search of the cannon is to establish where exactly did the Afghans attempt to cross the Chenab. There were two crossing sites on the Chenab: Rasulnagar (previously known as Ramnagar) and Wazirabad. Singh points at Wazirabad, explaining that in the first three invasions between 1748 and 1751, Abdali crossed the river at Sohdra, 6km to the northeast of Wazirabad. On his fifth invasion (1759-61), at the end of which he attempted to take the cannon back, he entered through the Bolan Pass and crossed the Indus from Bannu District but returned to Kabul via Wazirabad in 1761.

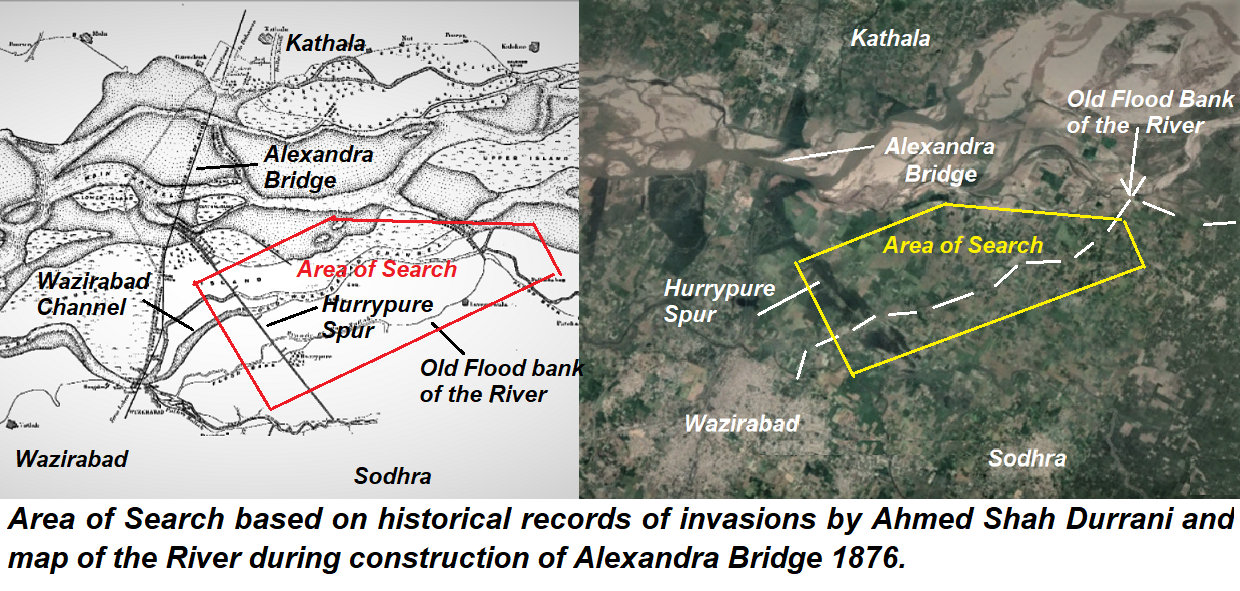

In ‘The Alexandra Bridge, Punjab Northern State Railway,’ a paper written by Henry Lambert around 1880, he states that ‘During the winter the river was contained in a 500yard-wide and 10 to15ft-deep channel.’ By the middle of April, floods from the melting snow on the Himalayas increases the volume up to the middle of June, when the monsoon commences’. During the monsoons, the Chenab would spread up to 5.6 km westward from Wazirabad. The earliest sketch of this area made after the battle of Gujrat in 1849 shows the Chenab flowing past Sodhra and Wazirabad. When the British decided to bridge the Chenab, they constructed a Bell’s bund or guide bank to deflect the river channels away from the eastern bank.

The 1920 Gazetteer of Sialkot district states that during the previous century when the River Chenab debouched from the hills near Akhnoor, it split into two channels with the eastern carrying most of the water. After the 1885 floods that accelerated the westward shift, a barrage of stones formed across the river mouth opposite Akhnoor reduced the eastern branch to a trickle. A further shift westward was induced with the construction of the Alexandra Bridge and the training of the river.

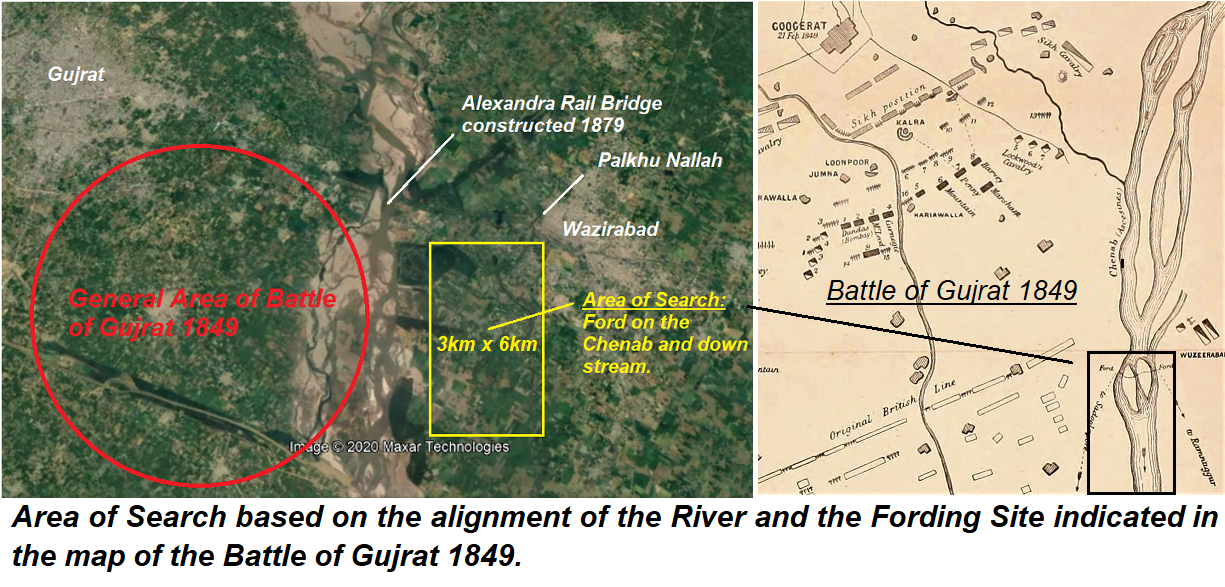

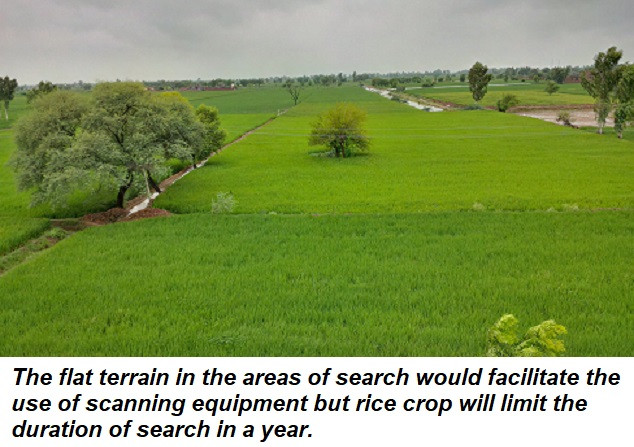

More relevant was the construction of a second bund called the Hurrypure Spur from Sodhra towards the southwest to protect the road and rail lines running up to the bridges. From our perspective, the shifting of the river channels westward is fortunate as it has exposed what were some of the main beds of the river channels. Consequently, there is now a 6km-wide agricultural belt between Sodhra and the river beneath which the cannon may be resting. While our primary focus is on the north of Wazirabad opposite Sodhra, another crossing site southward was used by General Gough’s army prior to the decisive 1849 battle of Gujrat. The fording site appears on a sketch of the battle and is worth exploring if Sodhra does not bear results.

The third site to study is the Rasulnagar crossing. It was an important ford across the Chenab as it lay on the route linking Lahore to Bhera, on the River Jhelum from where routes led across to the Indus and beyond into Afghanistan. Lahore was a wholesale market for rock salt and caravans from the Khewra mines used this crossing. Unlike upstream, there has been little westward shift of the river channels and the current alignment is nearly the same as a sketch made after the Battle of Ramnagar in 1848. Hence, only a 1½ km belt between the town and the riverbank can be searched.

A paleo-hydrological survey of River Chenab to reveal the remnants of its eastern streams subsequently buried by younger sediment would substantiate the above analysis. If the Soil Survey of Punjab does not possess the necessary information, soil samples at varying depth along the flood plain of the river must be collected. The results could then be validated against the 1849 and 1876 maps and information provided by locals.

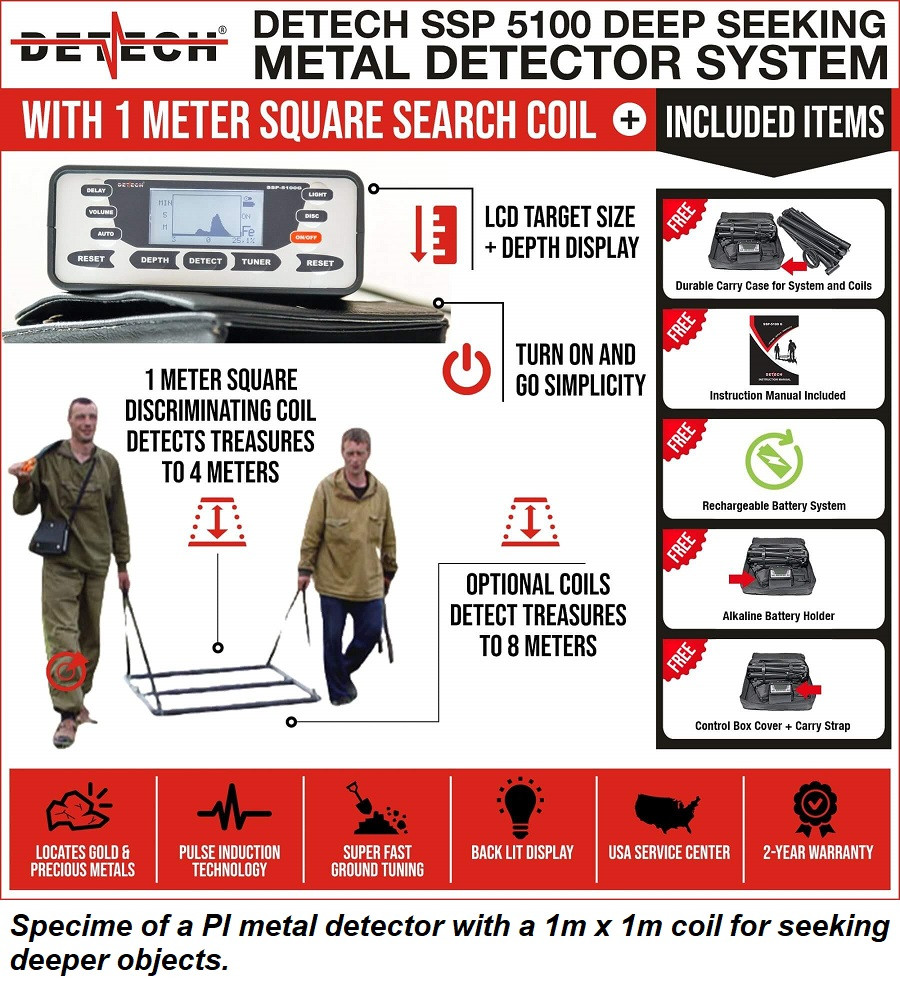

The next stage is to decide the equipment required for the sub-surface survey. It is a highly developed science with a wide range of products that cater to amateurs as well as professionals in the civil and military sectors. Hand-held metal detectors are commonly used by treasure hunters and a more sophisticated version by the military for detecting land mines. A more sophisticated version using the same technology as most hand held detectors is the Large-loop Detection System (LLDS), which enables a relatively fast search of 3-4 acres per day.

Another device that can detect subsurface objects up to 15 metres in depth is the ground penetrating radar (GPR). However, the nature of soil affects the depth to which the GPR can penetrate and loam (a mixture of clay, silt and sand with high humus content) poses a problem for GPR because its high electrical conductivity causes signal strength to be rapidly attenuated. The paper ‘The Alexandra Bridge, Punjab Northern State Railway,’ states that in the “…Wazirabad Reach, the Chenab had become wide to an abnormal extent. The fine sand of the bed was ascertained to be about 65 feet in depth, overlying clay of moderate consistency.” The department of soil survey of Punjab may have specific information on the nature of the soil present here.

Hunting for buried objects is neither cheap nor easy and there are chances that the cannon may be just out of the range for even the best metal detectors. The equipment for reaching greater depth and covering larger areas is Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT), which basically is the reading of changes in an electrical current as it passes through different materials. The barrel of the cannon will ‘resist’ the current much less than the surrounding soil. Professional resistivity metres can be expensive and difficult to use but there are cheaper options used by treasure hunters that can produce acceptable results but data logging and mapping capabilities are a must. In addition, there are a few companies in Pakistan that have the expertise and equipment, primarily used to study the soil for multistory structures with deep basements.

Having selected the detector and narrowed the area of search to manageable limits the next step is to survey the area and plot a grid. This is the time-tested method adopted by archeologists for digs and professional advice would be obtained from the department of archeology. A single primary square could be searched in 3-4 days and the entire area of the Sodhra crossing in a year considering unforeseen weather, etc. The crossing site at Rasulnagar would take less time since the area is smaller in depth. Since these crossing sites were used for at least two millenniums, the search teams may register a number of subsurface contacts. All contacts would be mapped and the ones with greater possibility would be resurveyed. Ultimately 3-4 sites would be shortlisted to dig. In addition to field and management expenses, the cost of detectors would be a major portion of initial investment in such an endeavor. Also add to that expenses for hiring excavators for the digs and compensation to the farmers for damage to their crops/fields. Finally, if the barrel is located, expenses of hiring of a crane and transport to a facility where it would be cleaned and restored.

Since the cannon was originally cast at Mughalpura, the restoration could be carried out by the Railway Workshop at Mughalpura. They would restore the barrel and mount it on a gun carriage similar to the Zamzama with the frame of north Indian rosewood or shisham and wheels made of gum Arabic tree or keekar because of its toughness. Someday, with input by professionals, someone with financial resources and the vision may materialise the quest to find the lost cannon.

The author is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com. All information and facts provided are the sole responsibility of the writer.