November is approaching. Noise over the next army chief has started to rise to a crescendo, and so has a media guessing game over who will pick up the baton. But why our political elite and media are fixated on one appointment, especially at a time when the country is reeling from the devastating aftermath of a deluge of biblical proportions? The unprecedented human suffering in the flood-hit regions has shocked the world, triggering an outpouring of empathy. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said that he has “never seen climate carnage” on such a scale. UNHCR special envoy Angelina Jolie was also “overwhelmed” because she has “never seen anything like this”.

The floods have accentuated fears of an economic default in the country, which was already facing a debilitating liquidity crunch. Revival of the IMF bailout programme, which was expected to dispel fears of default, has failed to restore confidence in the country’s financial system. High energy costs and runaway inflation, which clocked in at a record 27% in Aug 2022, have strangulated the middle and lower income strata. Preliminary estimates have put financial losses caused by the floods at a whopping $30 billion, further dimming the already faint hope of economic viability. Add to this mix bitter political polarisation and we have a recipe for disaster.

Ironically, the apocalypse couldn’t awaken our politicians to the plight of millions of people displaced by the floods. Personal agendas and petty politics have taken precedence over the human tragedy. Acrimonious exchanges have grabbed the spotlight as our content-starved 24/7 news channels need high-pitched verbal duelling to spice up their transmissions. This political circus has rendered the parliament redundant and democracy meaningless, leaving the young generation disillusioned as they see no hope in the country. This may sound like doomsaying, but we have been through this nightmarish déjà vu multiple times in the past. But this resilient nation has weathered every storm, beat all the odds, and steered out of every crisis, though battered and bruised at times.

1665294390-6/WhatsApp-Image-2022-10-09-at-10-33-12-(1)1665294390-6.jpeg)

During its short and turbulent history, Pakistan has oscillated between military rule, democratically elected governments, and hybrid regimes. A decade and a half of democratic rule has made one thing abundantly clear: the state’s service delivery arm, or the executive arm, cannot function properly or fulfil its purpose on its own. It simply does not have the capacity to manage colossal challenges, and natural disasters Pakistan has faced. Perhaps our political elites know this. Perhaps they have an unspoken understanding that we will have a “controlled democracy”, aided and guided by the security establishment. But ironically, our politicians have used the establishment as a whipping boy, or a scapegoat, or a bogeyman for their political agendas. They are fine as long as they enjoy the blessing of the security establishment, but the moment they fall from grace they turn their guns against the establishment. This underpins the real dilemma of Pakistani politics.

Despite this bitter-sour relationship, we have seen Pakistan tackling massive challenges with a relative ease when the civil and military cogs of the governance machine function in harmony. Without a symbiotic civil-military relation, it wouldn’t have been possible to successfully tackle the natural calamities like the 2005 earthquakes and the 2010 and 2022 floods, manage the Covid pandemic, fight locust attack, eradicate terrorism, implement CPEC, and surmount international challenges posed by FATF grey-listing, and avoid multibillion-dollar Reko Diq and Karkey penalties.

Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa, the incumbent army chief, will be doffing his uniform after the completion of his extended tenure later this year. Throughout these years, the military lent unflinching support to the previous PTI government, helping it steer out of multiple political, economic, security, and diplomatic challenges. But ironically the moment Imran Khan buckled under pressure from a bitterly antagonised opposition alliance, his supporters unleashed a sinister campaign against the national security institutions on social media.

A symbiotic relationship

Moeed Yusuf, who served as national security adviser in Khan’s government, attests to the fact that the military was in-synch with whatever the civilian government did. “In my two and a half years in office, I saw seamless and proactive coordination and cooperation between the civilian and the military leadership,” he told The Express Tribune in an exclusive chat. “From my vantage point, there were no policy issues where I had a problem. It was a mutually supportive space that we operated in. And I walked away with the firm belief that in Pakistan’s context, civil-military collaboration is actually a huge positive,” he added.

Lawyer and political analyst Saad Rasool agrees that a symbiotic civil-military relationship is what Pakistan needs. “Without the support of the military in the face of such challenges – without synergy between the civilian and military arms of the state – our institutions would have been overwhelmed,” said Rasool. “Our nation has prospered and functioned better when civil-military cohesion has existed. It is one reason why periods where Pakistan was under martial law saw better performance from the executive.”

But Rasool said Pakistan is not alone in this aspect. There are many such examples in other countries where tackling major challenges require synergy and cooperation between civil and military institutions. In the US, the civil bureaucracy has a lot of resources and experience at its disposal, yet in times of serious emergency like hurricanes, American civil authorities need support from their military counterparts like the National Guard. Similarly, in India the military is called in to assist the civilian authorities on certain challenges and initiatives.

Rasool said that Pakistan’s civil-military conundrum could be solved by introducing laws and creating a system where both arms have a symbiotic relationship. “The prescriptions for such functions should be stated in our Constitution in a way that factors this reality. It should have legal provisions that allow military assistance where needed with appropriate oversight mechanisms,” he suggested

“We are not at the point where we could have a classic sort of division of labour and within the bounds of law and the Constitution, I think, whatever support they can provide each other is good for Pakistan,” added Yusuf.

Overcoming two decades of terror

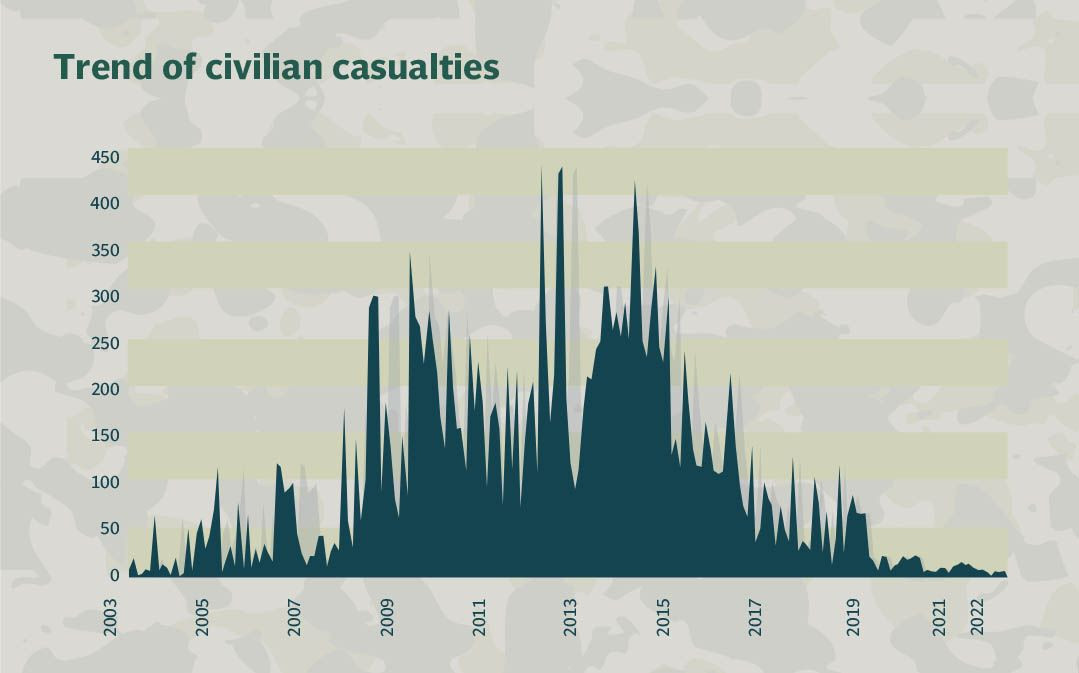

If there is one strand that dominates Pakistan’s experience over the past two decades, it is the country’s long and bloody struggle with terrorism emanating from the regional ramifications of the United States’ so called ‘War on Terror’. Between 2002 and 2022, the country suffered over 28,000 civilian and security forces casualties in more than 15,000 incidents of violence.

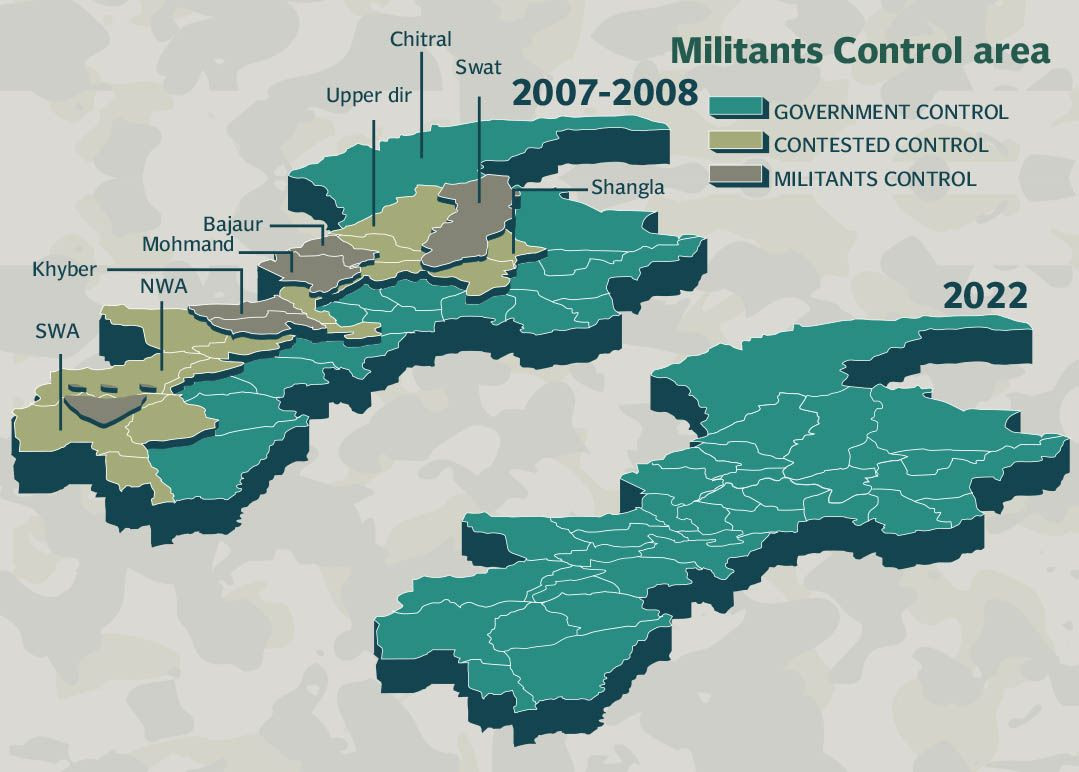

Following on to the gains made during 2014’s Operation Zarb-e-Azb, Pakistan’s security forces commenced Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad in 2017 and carried out more than 300,000 intelligence-based operations (IBOs) across the length and breadth of the country. In contrast to previous counter-terror offensives, which targeted a rather visible enemy in particular geographic locations for a stipulated timeframe, Radd-ul-Fasaad aimed to eliminate militant sleeper cells and facilitators wherever they were found.

The kinetic and non-kinetic operations were conducted even as security on Pakistan’s western frontier remained fraught and by the end, around 48,000 sq km of the country’s territory was freed of terrorist presence. The operation culminated with a range of welfare initiatives in terror-hit areas, many of which were once notorious for being ‘no-go’ locations. To prevent cross-border movement of terrorists, the Pakistani military also initiated the construction of a 2,611km fence along the Afghan border and a 909km fence along the Iran border.

Speaking about progress on the internal security front, former NSA Moeed Yusuf termed it one of Pakistan’s major success stories. “In terms of moving from a situation when terrorism was seen as an existential threat to Pakistan to a point where the threat remains but has been tamed to sort of local and contained kind of violence by either the Baloch militant groups or the TTP or some others… I think it is definitely one of the big success stories,” he said. “And most of them (remaining threats) if not all, are residing outside Pakistan, and are being supported externally in that sense.”

Social policy analyst Abid Qaiyum Suleri linked Pakistan’s success on the internal security front to the country’s larger economic viability. “Without the eradication of terrorism in the country, Pakistan would never be on the progressive economic trajectory,” he stressed. “People in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad used for fear going outside their homes fearing they may face blasts. Peace has provided us with a conducive environment for economy and the investors are coming in seeing this stability,” he pointed out, adding that this peace would not have been possible without civil military synchronisation.

Yusuf cautioned, however, that there is no room to be complacent. “We still have to work on the deeper issues that were envisioned in the National Action Plan, in terms of changing mindsets, in terms of ensuring that there are no factories where radical mindsets can be radicalised, access to weapons, terror financing, we've done very well, courtesy FATF. But in that whole multifaceted and holistic approach, we can't take our eye off the ball because the threat is not completely eliminated.”

Touching on peace talks with the TTP, Yusuf said these conversations took place because of a perceived window of opportunity. He added, however, that the state has to draw its red lines very clearly when the constitution of Pakistan is upheld. “There will be no state within a state. We cannot allow a group to find itself emboldened against the state again, so these challenges will continue.”

National security policy

To build on the gains in terms of internal security and to outline a vision that consolidates Pakistan’s economic future, connectivity, internal and external security in a wider regional and international context, the country’s first ever national security policy was unveiled at the start of this year.

Former NSA Yusuf, who was one of the key figures behind the policy’s formulation, stressed while speaking to The Express Tribune that such a document is “useless without a civil-military consensus in the Pakistani context.”

“Without civil-military consensus, there is no possibility that this document could have been finalised, produced, approved and formalised. And I’m on record saying this that there was 100% support from the civilian side and 100% support from the military side.”

According to Yusuf, the way this policy has been framed, no government or leadership will be able to shy away from it. “I think this is reflective of national consensus, even if there is sort of political wrangling and conversations that may not be all positive.” That said he identified the deeper issue as a lack of maturity in Pakistan’s present system. “The lack of evolution in our system holds back good developments. We have not matured to be able to determine and continue on what everybody agrees are positive steps,” he said, adding that as a system, we are still hung up on anxiety over someone else getting the credit.

Yusuf stressed that overarching decisions, documents and policies like the NSP need to be owned by the entire state. “And they need to be continuous because NSP results are not going to be visible in a year, two years, three years, five years. This is a 15-20 year process.”

He urged the country’s various policymaking stakeholders to ensure that we find a way where certain things remain above politics and will continue to be pursued if they're considered to be positive, regardless of who's in office.

Pivoting to geoeconomics

Last year, senior Pakistani officials, the army chief included, outlined a vision for Pakistan’s foreign policy that emphasised geoeconomics and regional integration rather than the country’s geostrategic importance. The idea was even incorporated into the NSP and the country’s wider security conversations.

Speaking about the topic, Moeed Yusuf said that the military leadership respond positively to this reorientation. He noted, however, that there is a general lack of nuanced understanding regarding the term. “It is a contested term. It's a term that came out at the end of the Cold War that had different connotations.”

“Very simply, geoeconomics and geostrategy are the same thing, the two sides of the same coin,” Yusuf clarified. “We are not shifting or ousting one and shifting to the other. It is just a matter of putting more emphasis. It is the approach which is going to be economy centric, rather than traditional security centric,” he explained.

According to the former NSA, this doesn’t mean you undermine traditional security or are oblivious to your neighborhood challenges. “You are not prepared for adversaries to do bad things to you — that's not the point at all. The point is that you focus on building your economic security while catering to all the traditional security aspects rather than catering for most traditional security aspects and then thinking of the economic security aspects as an afterthought,” he said. “An example I give is if there is a security incident on the Pakistan Afghanistan international border, do you as a knee jerk shut down the border? Or do you first cater to ensuring that the trade, facilitation of the commerce engagement will continue or will not be harmed while you also take care of the security problem?”

In conversation with The Express Tribune, Yusuf further illustrated the country’s geoeconomic reorientation in action with respect to developments in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of US forces. “We talk about connectivity in our national security policy and we talk about geoeconomics, but look at our neighborhood. I don't know of any other country in the world that has two Western peoples that are isolated globally and sanctioned, and an Eastern neighbor that we don't have a conversation with. It's only with China that we have connectivity,” he said.

“So when you talk about Afghanistan, we don't want a country next door that's isolated and/or sanctioned. It's in our national interest to have a stable neighbour because one of our key nodes of connectivity is to Central Asia and onto Eurasia,” Yusuf added. “If Afghanistan is not economically stable, it's always threatening another mass migration. If it is threatening terrorism from its soil, it obviously is a big challenge for Pakistan.”

On the topic of US withdrawal, the former NSA said Pakistan managed it fairly well. “The timing was never predicted; nobody thought that Kabul would fall as quickly as it did. There have been minor incidents on the border. There are new equilibria to be arrived at. But overall it hasn't caused a direct major fallout in terms of a mass refugee problem again,” Yusuf noted.

Ensuring economic viability

Speaking on the importance civil-military cohesion for Pakistan’s economy, Suleri pointed to the aforementioned NSP. “If you see the National Security Policy, which was launched by the previous government, economy is the central pillar of it. It is one of the most crucial non-traditional security threats,” the social policy analyst noted in an exclusive chat, pointing to the examples of Russia and Ukraine, and Iran and North Korea. “If we see the case of Russia, it is mostly denting Ukraine with economic blows while Pakistan is helping the latter. The economic sanctions case can also be seen in the case of Iran and North Korea,” he said. “So, it is very important for a country to have a viable economy and ensure its economic prosperity, and economic growth and stability is as important for a civilian leadership as it is for the military.”

1665294390-3/WhatsApp-Image-2022-10-09-at-10-33-11-(1)1665294390-3.jpeg)

On a possible way forward, Suleri suggested walking in the pattern of the national security council, in which the central and provincial governments as well as military leadership is on board. “A national economic security council may be formed as a similar constitutional body in which chief ministers of all four provinces will be a part, while it would also have the prime minister. Similarly leaders of opposition in the parliament and senate should also be part of it and it should also have military leadership,” he said, adding that “If we want to implement the national security policy in letter and spirit, then such a constitutional body must be formed so that there may be a political consensus and no plan is politicised.”

According to Suleri, clarity and consensus are vital with regards to Pakistan’s most pressing economic challenges, such as debt management. “We must develop consensus over how to proceed with the IMF program. We must agree on how to carry our public sector enterprises, including how to revamp them or revive them or privatise them.” Highlighting the challenges for a civil government trying to tackle this on its own, the analyst told The Express Tribune any political party once elected must contend with the opposition. When it fails and the opposition party now finds itself elected to power, the cycle repeats. “This policy should end and consensus should be evolved on core issues such as privatisation, public sector enterprise, debt, IMF programme etc. They can engage in politics on all other issues.”

Suleri added that while the military should not be directly involved or lead the process, it should be ready to be part of it — “perhaps in a mediator’s role.”

Military diplomacy

Diplomacy has transformed overtime and has been changing shapes that necessitated roles of multiple stakeholders, said diplomat Nafees Zakaria. “Economic diplomacy, military diplomacy, backchannel diplomacy, track-I and track-II diplomacy, cricket diplomacy, and Ping-Pong diplomacy have been invoked from time to time,” he added.

There no denying that the security establishment has bailed out Pakistan through vigorous in-sync diplomatic efforts with the civilian arm of the state every time the country faced a liquidity crunch or threat of international isolation. Be it socioeconomic and military relation with Saudi Arabia, the UAE and China, or revival of a shaky IMF deal, or CPEC, or FATF, military diplomacy has been of immense help.

“In the context of Pakistan, our peculiar geographical location, our neighbours, and historical background have a profound bearing on Pakistan’s relations with other states. Security to a great extent has been a prominent element in the conduct of Pakistan relations, especially with its neighbours,” said Zakariya, who has served as Pakistan’s ambassador to the United Kingdom.

“It is in this context that, the military is a prominent player. It has significantly contributed in the diplomatic efforts by the Foreign Office. When it came to threats to our security, sovereignty and territorial integrity under various manifestations and not to conventional war, the armed forces of Pakistan have played a sterling role in pacifying the matters through deterrence, interventions and negotiations,” added Zakaria, who has also served as spokesperson of the Foreign Office.

Pulwama incident is one of many examples where our armed forces defeated the Indian designs to malign Pakistan, according to Zakaria. Dialogue over water issues, border-related issues, etc, have significant contributions from Pakistan’s armed forces.

“In the context of international peace and UN peacekeeping efforts, armed forces have earned respect and prominence at the international arenas. The military attaché offices, security institutions officials posted in Pakistan’s missions abroad contribute towards attaining goals and consolidation of foreign relations in a variety of ways.”

‘Game changer’ corridor

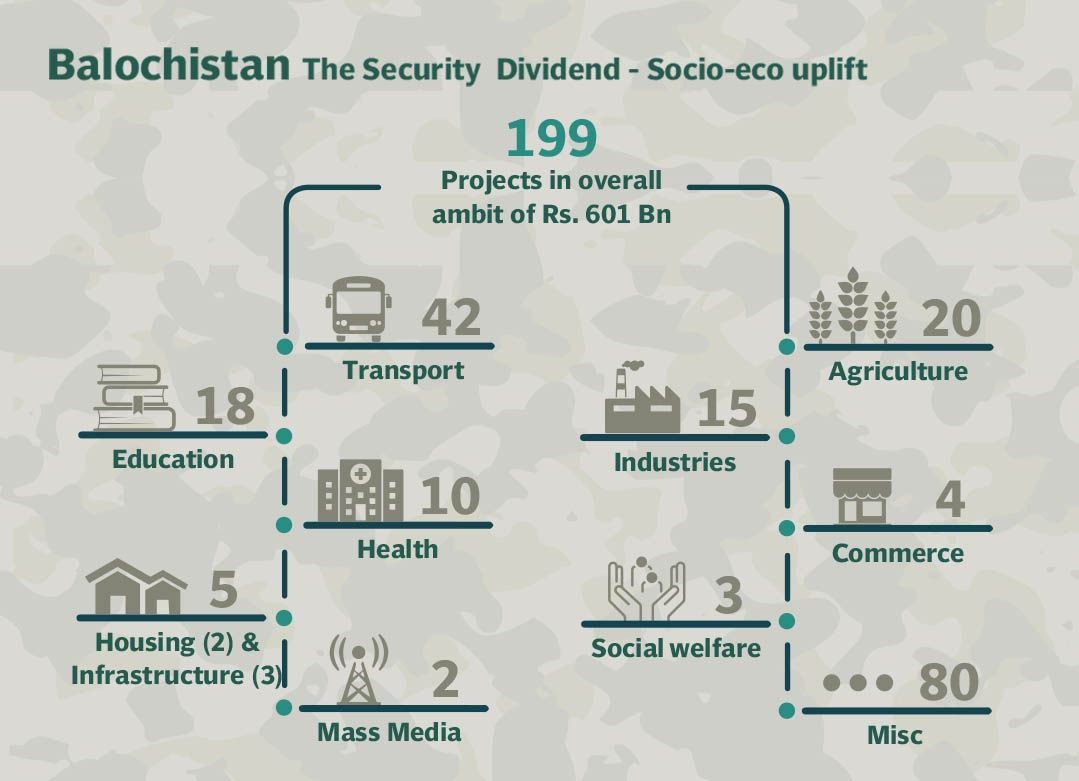

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which has been described as ‘game changer’ for Pakistan, is to propel the country into an unprecedented era of growth and development by modernising industries, infrastructure, transportation systems and energy generation sectors. However, India has publicly opposed the multibillion-dollar project and, according to Pakistani intelligence agencies, is plotting to sabotage it by fomenting unrest in Balochistan. The military raised a special division for CPEC security, which implemented multiple plans in accordance with the threat levels and perception and rendered countless sacrifices in the process.

“Developing CPEC would have been difficult given the law and order situation in Balochistan. The first component in CPEC is of a road network. The second component is of the [Gwadar] port, so given the situation in Balochistan that could never have happened without the military’s intervention or military’s role i.e. maintaining law and order in the volatile province,” says social policy analyst Abid Qaiyum Suleri.

1665294391-4/WhatsApp-Image-2022-10-09-at-10-33-11-(2)1665294391-4.jpeg)

Apart from security, political consistency is also important for the implementation of CPEC. However, the bitter political polarization in Pakistan, the stakeholders need some sort of assurance from the strong power centers.

“In Pakistan, we have more than one power center - the parliament, the media, and the army - which all had their role to play to reduce polarization,” he says. “I would say that the assurance we gave had an important role of the army chief. The army also supported the previous government. It also helped the current government. A strong assurance was given on the government's behalf,” he says.

International litigations

The mishandling of Karkey and Reko Diq cases had resulted in a financial nightmare after Pakistan lost its cases in the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes which slapped a massive fine of $1.6 billion and $11 billion, respectively for reneging on contracts with a Turkish and a Canadian firm. It would have been extremely difficult, if not impossible, to pay the colossal penalty. Who is to blame for the catastrophe and who helped avert the resulting financial doom?

“It must be said that the blame does fall on the civil side – the judiciary of the time, then chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry and the civil administration. Under the fear of the then judiciary, really poor legal advice was provided to the state with the main aim of avoiding Iftikhar Chaudhry’s wrath,” recalls Rasool.

He adds that when Pakistan faced the exorbitant penalty, those who looked after Pakistan’s strategic interests – and it is established that Pakistan’s economy is a strategic interest – were co-opted into tackling this issue. “Without Pakistan’s military exercising its leverage, some of this fine would have had to be paid and we simply did not have the ability to do that,” he adds. “It was the only way to get Pakistan out with its dignity intact and for that, the people of Pakistan owe a debt of gratitude to their armed forces.”

He adds that when Pakistan faced the exorbitant penalty, those who looked after Pakistan’s strategic interests – and it is established that Pakistan’s economy is a strategic interest – were co-opted into tackling this issue. “Without Pakistan’s military exercising its leverage, some of this fine would have had to be paid and we simply did not have the ability to do that,” he adds. “It was the only way to get Pakistan out with its dignity intact and for that, the people of Pakistan owe a debt of gratitude to their armed forces.”

Pandemic mitigation

As the Covid-19 pandemic engulfed country after country in 2020, Pakistan was at one point looked like it was heading straight for a health disaster. Its medical infrastructure at the outset appeared woefully inadequate. Some initial missteps led to an early surge in cases leaving the country to choose between bad or worse: close down the economy or let the virus play havoc.

Two years on, however, Pakistan’s handling of the pandemic has emerged as a regional and international success story. While neighbours India and Iran struggled with a deluge of cases and fatalities, Pakistan was able keep numbers manageable. The National Command and Operation Centre (NCOC), established and enabled with support from both civil and military authorities chalked out an effective strategy of testing, tracing and targeted rather than blanket lockdowns. It also managed a successful vaccine rollout that succeeded in inoculating as many as 100 million Pakistanis to date.

Speaking to The Express Tribune, Dr Faisal Sultan, who oversaw Pakistan’s Covid-19 response under previous prime minister Imran Khan, said a number of factors played a role in keeping Pakistan’s case count manageable. “These included a coherent, credible and data-drive scientific response. Our strategy to balance disease control and public welfare and economic well-being was constantly fine tuned and adjusted to match the epidemic numbers. Preparedness of the health system (testing, beds, oxygen supply, PPEs, training, vaccine supply and vaccine deployment) was also important. The NDMA played a crucial role all through the pandemic,” he said. He noted that the NCOC was pivotal in ensuring that the pandemic response was not haphazard and that not only were decisions science based and epidemiologically driven but that implementation and follow through was solid.

Speaking about the setting up of the NCOC, Dr Sultan said the idea came in mid to late March when it became clear that without national coherence, there will be great difficulties in a devolved, federal-structure country. “The National Security Council identified the risk and suggested to the PM to create the NCC, whose operational entity was the NCOC,” the former SAPM said. “It would have been a struggle to manage the pandemic effectively without a central entity such as the NCOC (or the newly created CDC in the NIH),” he stressed.

1665294390-1/WhatsApp-Image-2022-10-09-at-10-33-10-(1)1665294390-1.jpeg)

Dr Sultan added that the NCOC was “an effective forum where the federal government with its various arms (planning, NDMA, health, interior, aviation, religious affairs, information – in fact almost every single ministry) and the provincial ministries and government were able to sit in one room (often virtually and very often in person) with colleagues from the military who ensured seamless coordination, follow up and work. I think it was a great success.”

Lauding Pakistan’s Covid-19 response, social policy analyst Abid Qaiyum Suleri said there was a strong partnership of the civilian and military sides during efforts to tackle the pandemic. “Had there not been such partnership, we would have seen much more serious repercussions. India and Pakistan have a similar sociopolitical climate, but in India the Delta variant went out of control and took precious lives. In Pakistan, the Delta variant did not do much damage due to coordination between the government and the military.”

During Dr Sultan’s tenure as SAPM, Pakistan was also praised for its efforts to eradicate Polio. Speaking about how the country overcame logistical challenges, he said what helped us was great cooperation between the federal and provincial governments and health departments and polio and EPI programs. “The main challenges were (and are) the difficulty of having uniformly high quality campaigns in some hard to reach populations.”

He added that reduced mobility during the Covid era also probably helped and surveillance data from patients and the environment has helped in mapping the trouble spots to enable targeted response. “All these were and will be crucial to eradicate polio. We should not be demoralised by some recent detections, but should be energised to enable high quality campaigns in some key areas such as Southern KP and some parts of large cities like Karachi with mobile populations.”

International cricket’s revival

More than a decade of deadly war against terrorists cost Pakistan immensely in men and treasure. In the process, Pakistan became a big no-go area for foreigners while the perception was further accentuated by the negative press it received in the West. A 2009 gun attack on the Sri Lankan national team virtually ended international cricket in Pakistan. However, the military stamped out terrorism following a series of operations and paved way for return of normalcy in the country.

Ihsan Mani, a former chairman of Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB), is credited for the revival of international cricket in Pakistan at a time when the country was struggling to shake off the negative media portrayal due to a deadly war on terrorism. However, Mani says it wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the security agencies.

“The biggest challenge was to get the first country to tour Pakistan. I decided we should have Sri Lanka first. It was the Sri Lanka team that had been attacked in Lahore in 2009. If they came, then no other country could refuse,” he recalls. “We also involved the Military Attache at the Sri Lanka Embassy and encouraged him to speak to our military security agencies directly, which he did and was able to assure the Sri Lank Cricket Board that the security arrangements in Pakistan would be second to none.”

1665294390-8/WhatsApp-Image-2022-10-09-at-10-33-13-(1)1665294390-8.jpeg)

“Our military security agencies contacted their counterparts in Sri Lanka and were able to provide them with convincing assurance that their team would be safe in Pakistan. Without this support the tour would have been jeopardized,” he added.

Sri Lanka’s tour was followed by tours by Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, MCC and South Africa. More recently Australia and England have also toured Pakistan. The chairmen and /or chief executives, board members and their respective security consultants all made pre-tour visits to Pakistan and received comprehensive briefing from our security agencies.

The return of international cricket to Pakistan has had a very positive impact in parts of the country which were perceived as dangerous or not as secure as other parts of Pakistan. Cricket has played a major role in this. Since introducing the new structure of domestic cricket in 2019, teams from K-P have been dominant in the Quaid-e-Azam Trophy as well as in the 50- and 20-over tournaments. “I strongly believe that cricket in particular and sport in general gives a very powerful message to the world that Pakistan is open and safe for business,” he adds.