When I heard the story of two brothers from Karachi who, from the age of one to seven, saw all their fingers shedding off, I knew I had to find out what had afflicted them. It was not because of anything the children had done. According to a medical diagnosis years later, it happened because of their parents’ consanguineous marriage.

Grabbing something hot and not feeling the heat will burn your hand; you develop blisters, and blisters can turn into a wound. If you are a normal person, you apply some ointment and/or keep it bandaged for a few days until it is healed. But that is not the case with Zaman brothers Muneer and Mohsin.

Muneer, the oldest of the three sons of Zaman, couldn't feel heat on his hands and feet from an early age. Being a child, he used to grab hot things but felt nothing and ended up burning his hand, but he never cried. He used to develop blisters and wounds on his fingers. His parents tried everything to heal their child's fingers, but nothing worked. Instead of being cured, the damage became so severe that the distal phalanx (top part of the finger) fell off.

24 years to find a disease

That was not just a one-time occurrence. By the time he was seven, the distal phalanx of all his fingers fell off the same way, and that terribly worried his parents. All those years, they could not understand Muneer’s illness. Muneer’s parents and doctors failed to understand the cause of what was happening to Muneer. All his test reports were clear. He had nothing that could be stated as the reason for what was happening to his fingers. At that time, it was not limited to his fingers but also spread to his feet.

The younger brother of Muneer was fully healthy and had no disease or disability, but the third sibling had the same disease. Their parents went to many doctors and hospitals, but no one had a diagnosis. Seeing their second child healthy assured them that what their two other sons had was not contagious.

It took them 24 years to diagnose the name of the disease—hereditary motor sensory neuropathy (HMSN), also known as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. For years, doctors could only assess that it was due to the consanguineous marriage of Muneer's parents. The disease is an inherited, progressive disease of the nerves with weakness and numbness, more pronounced in legs than arms. Parts of the nerve cells deteriorate.

Muneer's parents were first cousins. His mother lost her life while battling Hepatitis C. Muneer was nine years old, and his youngest brother was one. Muneer had lost all his fingers and had little confidence to face the world. Not long after he lost his fingers, he got a bruise on the ankle of his right leg. As soon as that happened, he was sure he would lose his foot too. “I have seen my fingers falling, shedding off. I know the pain, and I know how it happens. When I was hit on the ankle, I thought it would not stop there and end as my fingers did. My grandparents took me to every hospital and did every test, but nothing cured me. They didn't know what was causing it, so they didn't know how to cure it. What I learned all those years was that there was no cure. You just have to be careful with yourself," Zaman tells The Express Tribune.

After years of allopathic and homoeopathic treatments, the disease was not cured. A homoeopathic doctor gave Muneer an ointment to put on the wound. Munir says, “The doctor didn't see the wound but prescribed the medicine. In three days, the wound worsened to the extent that a scissor had to be inserted all the way to clean the wound. The only option left was to cut off my leg to stop the infection from spreading. I had done nothing, but I suffered the loss of my fingers and leg. I was so demotivated with my life. I was deeply scared. I didn't meet anyone as everyone asked me about my hands and leg, and I didn't have the courage to tell them or talk to them. I stayed in my room for years.”

After Muneer's mother's death, Zaman remarried. His second wife was not supportive of his children, and he soon disowned Muneer and his youngest son Mohsin who had the same disease. After that, it was Muneer’s responsibility to take care of his brother as well as his own issues. Muneer's maternal uncle, a Careem driver, found out about the Disabled Welfare Association (DWA), an organization that works to empower differently abled people.

Coming to terms

At DWA, Muneer and Mohsin have started a new life and are now getting an education, doing things, and participating in extracurricular activities. "We live here now and visit our father once a week. I lost hope of living a normal life before coming here. When my uncle talked to me and brought me here, DWA did my counselling. They showed me how other differently abled people are living their life happily. I saw them working daily routines, playing cricket, and getting an education. That motivated me, and I decided to change my life," he says.

DWA is a Sindh-based organisation for people with disabilities (OPD) and is serving humanity for the last two decades. It has adopted a diversified approach to bring comfort to lives of people with disabilities. It addresses every disability relevant issue, including advocacy and disability awareness, mobilization of home-confined PWDs, youth motivation for their capacity building, career-oriented training, provision of assistive devices, and seeking outreach and recreational activities.

The 24-year-old Muneer has been here for the past three years. Muneer received education from DWA, and was then offered a job as supervisor, handling logistics and routine work of the organization. He is also doing a computer course to make a better living. He has been provided with an electric wheelchair, which has made his life a lot easier. "I do everything on this wheelchair. I get to places, my home and markets; it has given me legs and empowered me to do everything on my own," says Muneer, who cannot walk because after losing his right leg, he started to rely on his left leg to walk, which caused an ankle injury. Nw he can’t put any weight on his left leg.

For Muneer, wheelchair has prevented him from getting further injuries and losing more body parts. "If I was at home, we weren't aware of not crawling, which could create a wound and damage the leg. Coming here helped in getting my previous wounds healed and prevent a further injury," he says. After watching the environment and the care at DWA, he decided to bring his younger brother Mohsin with him. Now Muneer and Mohsin live at DWA and visit their father every weekend. "I had decided that whatever happened to me, I won't let it happen to Mohsin, and that is why I brought him here. Right now, he has some wounds on his fingers, but they will be healed soon, and then he can take care of not getting any injury on his hands and feet," he says.

After consulting almost every doctor in Karachi, a Canadian-based doctor, Iftikhar Ahmed, was contacted. He diagnosed the disease as a rare one in Pakistan. “As it is not much diagnosed, there is no permanent cure or treatment for this disease in Pakistan. We will have to go abroad if we want some good treatment," says Muneer.

A high degree of kinship

Scientists say inbreeding has caused an unusually high number of genetic mutations to spread across Pakistan, creating disabilities for children of inbreeding. Nevertheless, this social convention persists. Chromosomal, genetic, and congenital abnormalities can affect any family regardless of background or ethnicity. Most babies born to consanguineous couples are healthy. Marriage between first cousins increases the risk of birth defects from three percent to six percent, but the absolute risk is still small. Cousins' marriages are the cause of only one-third of birth defects.

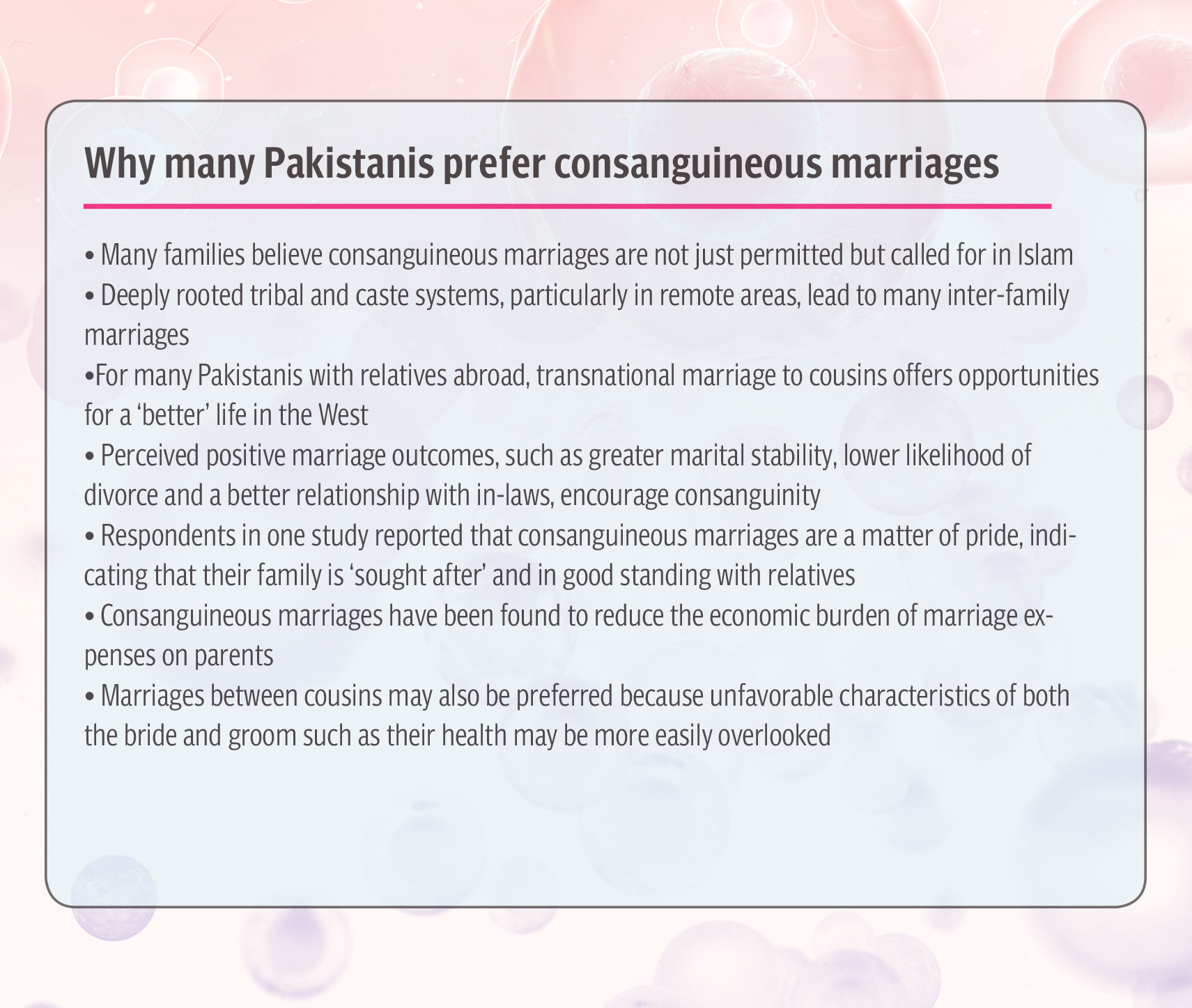

Despite knowing the consequences of consanguineous marriages, people are still pressured to marry first cousins due to the enormous familial and social pressure. Many people who refuse to consider the option of inter-familial marriage for their children risk being ostracized.

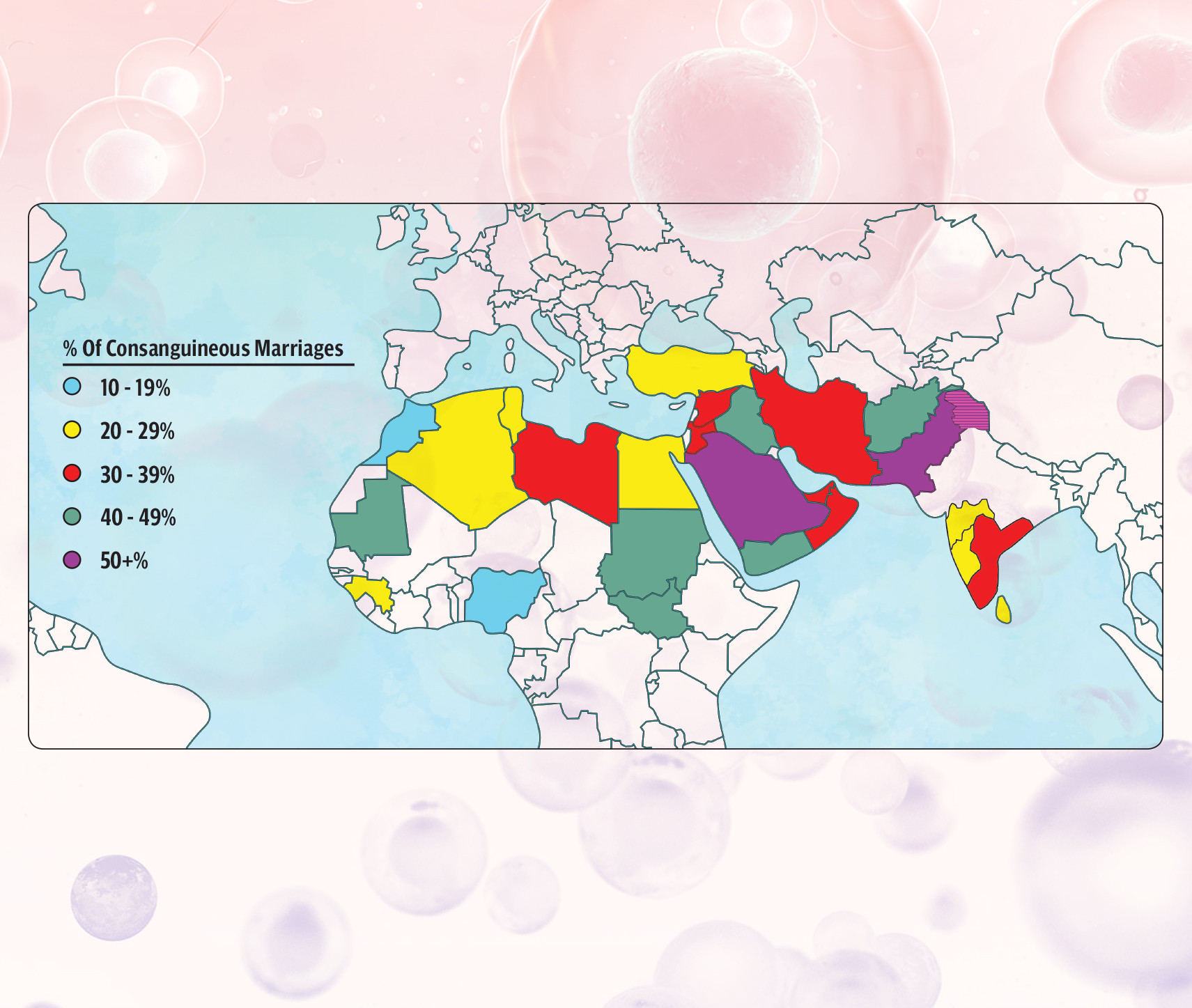

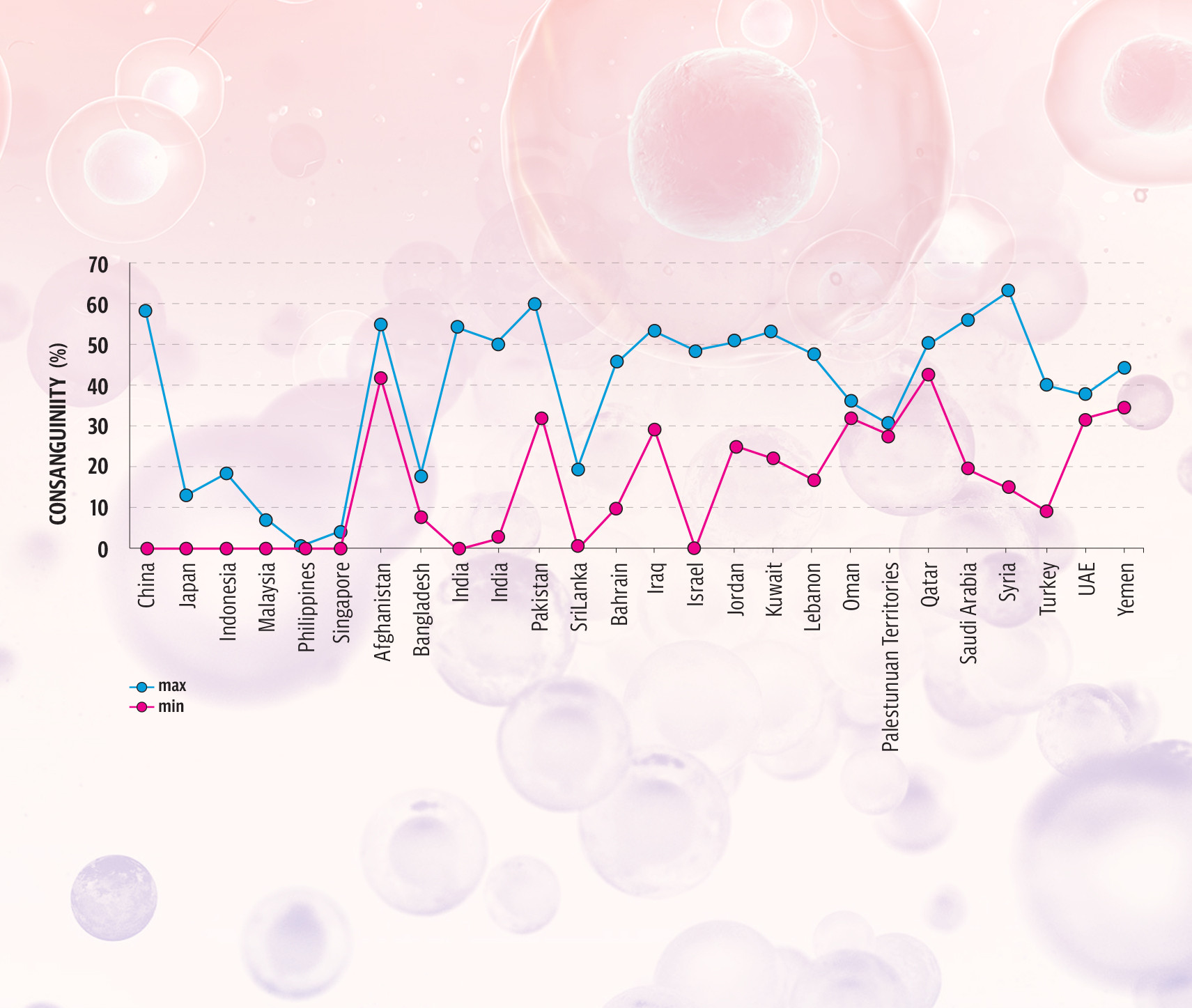

According to the 2012-2013 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, Pakistan has a high rate of marriages between cousins. Half of all marriages occur between first cousins. First cousin marriages are lower in urban areas (38 percent) compared to rural areas (54 percent). First cousin marriages range from 53 percent in Sindh to 40 percent in ICT Islamabad and Gilgit Baltistan.

The 2017 report on genetic mutations in Pakistan states that the “heterogeneous composition" of the Pakistani population, including a high degree of "kinship", has led to the prevalence of genetic diseases. The report presents Pakistan's “genetic mutation” database that identifies and tracks different types of mutations and disorders. According to the database, Pakistan has over 1,000 reported mutations in 130 different types of genetic disorders.

Globally, one billion people live in countries where interracial marriage is common. Of this billion, one in three people is married to a second cousin or a close relative. Frequency of inherited diseases in such children is about twice that of children of unrelated parents.

In Pakistan, half the population is married to a cousin; the number is higher than in any other country. In rural areas, this could be 80 percent, says Hafeez-ur-Rehman, an anthropologist at the Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad.

Dr Zaib Taj, a medical officer at DWA, faced an injury after being shot from a police van that left her disabled, with a spinal cord injury and paralysis. As her disability was permanent, her husband soon divorced her, and she was left all alone for seven years, during which she faced prolonged depression, low self-esteem, and isolation at home.

Despite her low morale, Dr Taj managed to bounce back and become a role model for other women with disabilities. "Whether it's public transport or road infrastructure, people with disabilities face new challenges everywhere. In addition to the integrated healthcare system, there is a general need to update the entire infrastructure at every level," she says.

Dr Taj gives counselling to differently abled people at DWA. She says that many parents are unaware of diseases that may occur because of a marriage between cousins. "There are many types of disabilities caused by consanguineous marriages. Muneer and Mohsin are prime examples; they got their disease from their parents. So many cases of people with diseases that developed due to cousin marriages," she says.

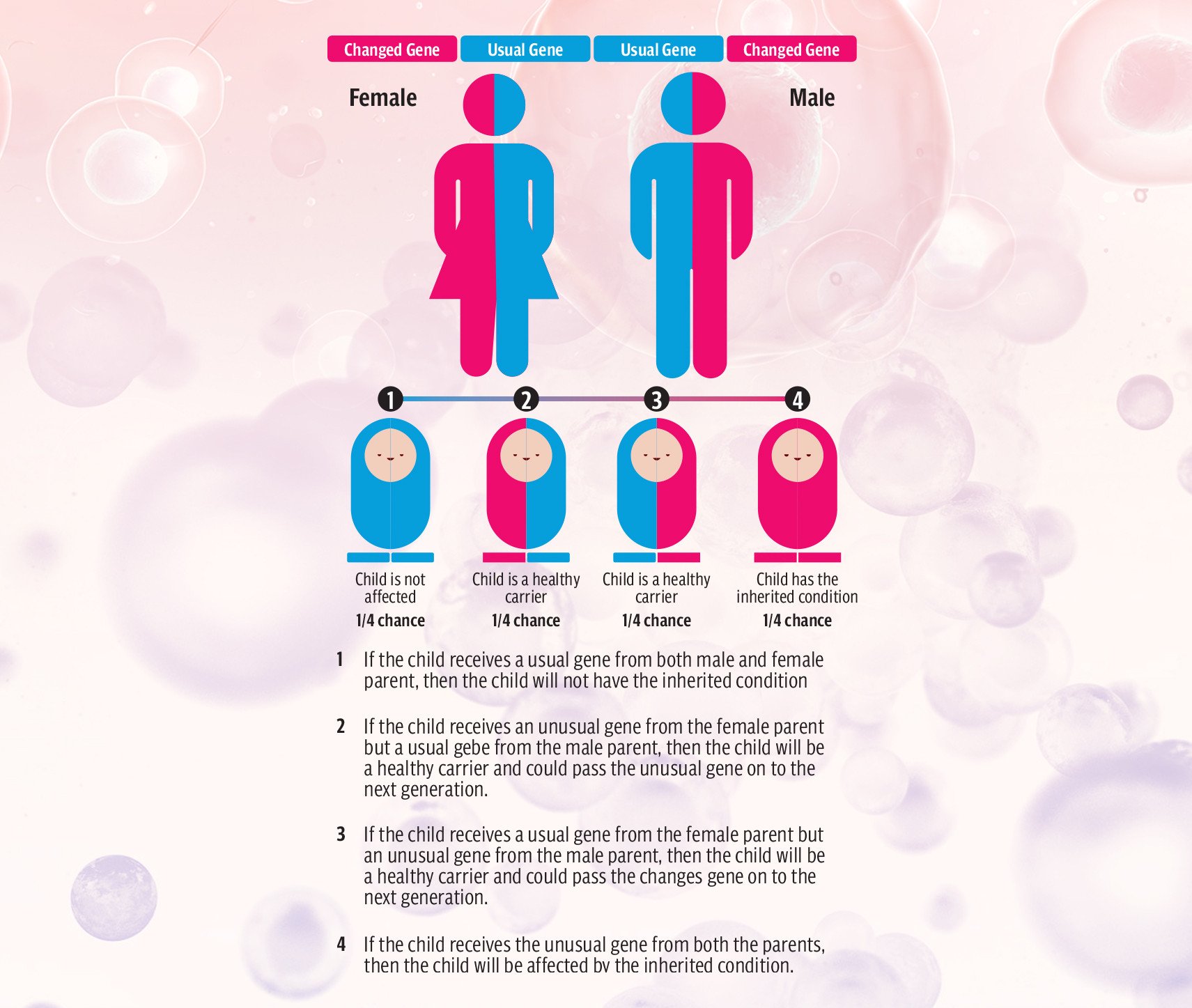

In the context of Muneer and Mohsin having disabilities and the third brother being perfectly healthy, Dr Ramzan, who studies genetic disorders, explains that marrying a cousin is not the reason for a child to be born with a disability. Most babies born to cousin couples are healthy. "The problem arises when there is an abnormal gene in the family, and both parents carry the abnormal gene. In such couples, with each pregnancy a child may inherit the condition. This occurs when a child inherits an abnormal gene from both the father and mother. If a cousin pair has a healthy child, it may be because they do not have the abnormal gene or because the child did not inherit the abnormal gene from both parents. A young person may be a carrier of the condition because they inherited one common gene and one abnormal gene. Alternatively, they may have inherited two common genes, one from each parent.

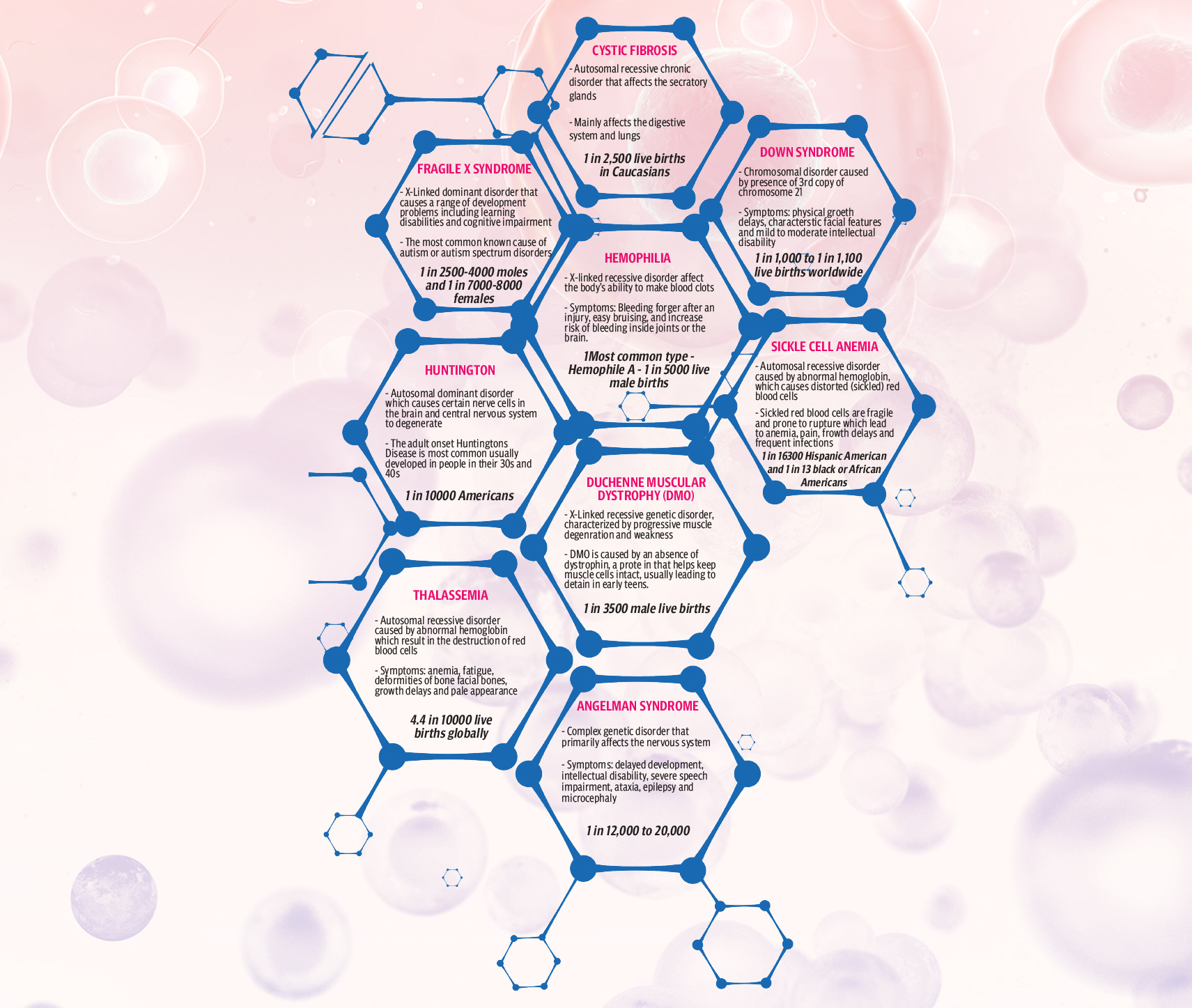

Besides the Muneer and Mohsin case, a rare one in Pakistan with only a 10 percent rate, there is another common disease that originates due to consanguineous marriages: muscular dystrophy. It is a group of conditions that causes progressive weakness and loss of muscle mass. In muscular dystrophy, abnormal genes (mutations) interfere with the production of proteins needed to form healthy muscle. There is no cure for muscular dystrophy, but medications and therapy can help manage symptoms and slow the course of the disease.

Religion and marriage

Pakistan being an Islamic country, people here firmly believe that marriages in family are by Islamic sharia law and the traditions of Prophet Mohammad (pbuh). A health expert, working at a government-initiated project for raising awareness for consanguineous marriages, spoke on condition of anonymity. The person says that many families in Pakistan practise consanguinity because they believe it is mandated by the religion. "Even if government tried to make such marriages illegal, there would be strong opposition. Tribal and caste systems are deeply rooted in remote areas of Pakistan. The caste system, especially among people living in Punjab, is rigid, leading to many marriages between families. Several genetic disorders are common in this community. In Pakistan's western Balochistan, southern Sindh, and north-western provinces, tribal systems dominate family life.”

Some highly populated areas, with families living in the same location for a long time, face these issues. Manghopir, for instance, the rural area of Karachi, is full of consanguineous marriages, and many children have disabilities, mostly caused by inter-family marriages.

In March 2020, the then Government of Punjab formed the Genetic Diseases Prevention Task Force. Lahore Children's Hospital is now collaborating with the German diagnostic company CENTOGENE and other international organizations to provide free genetic screening services. Prenatal screening helps parents decide whether to terminate a pregnancy if a fatal disease is found. Early detection also helps treat children born with genetic disorders. "We have tested more than 40,000 families in Pakistan with suspected genetic diseases," says a government official.

One other reason why PWDs in Pakistan have fewer facilities is because there is no registration mechanism. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics estimates that 31 million people suffer from one disability or the other. However, NADRA records show only 371,000 people with disabilities in Pakistan. This may be due to the strong stigma attached to persons with disabilities in the country, making them hesitant to declare their disability.

Encouraging disability registration, government subsidies, free testing, finanicial and other support, and improved social protection plans are some of the much-needed steps. By registering PWDs, institutions will be encouraged to make special arrangements, such as accommodating accessibility issues and exceptional medical facilities. This registration, therefore, serves as an essential step in recognizing, addressing, and mitigating inequalities of persons with disabilities in Pakistan.

Much more must be done to change people's attitudes towards the dangers of having children with blood relatives. In matters given a religious colour, people have a blind faith, and they do not listen to logic. If government urges clerics to raise awareness of the rise in genetic diseases and their links to consanguineous marriages, perhaps more Pakistanis would take note.

Cousin couples, at any stage, can use genetic information, which is valuable for them and their family. A person with enough knowledge can make the right decisions. Genetic services can help people with a family history of genetic disorders or who have concerns about such conditions.