History, when seen through the lens of discrete ages, evokes the sense that a singular moment or a neat series of them divide the age before from the age after. The modern world as a distinct entity can appear to have different ‘parents’ – from the Age of Reason to the Industrial Age. In the same vein, many around the world today may recognise the two world wars of the past century as defining moments for everything we recognise as modern. From the shifts in political order globally to the impact on societies and cultures the mass movement of peoples – combatant and non-combatant alike – left; to the birth of several modern technologies we take for granted – jet engines and rockets, computers and nuclear power; as historian Kaushik Roy has written, “we are still being influenced by its ramifications.”

But when the story of the two wars is repeated, on our screens and in the pages of popular books, some nations and people seem to get all the limelight. Others, despite the value of their contribution and the extent of their role, remain somehow forgotten.

More than four million men from present-day Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Nepal played a vital role in allied victories in the two wars. Yet their stories and feats, trials and tribulations are rather less well known.

The largest army in history

For much of the 19th century, there was no single British Indian Army in the Subcontinent. Rather there were three, belonging to each of the individual British presidencies – Bengal, Bombay and Madras. These three armies would be unified into one by 1891. By 1914, when the First World War rolled about, the force would be the largest volunteer army in the world at the time.

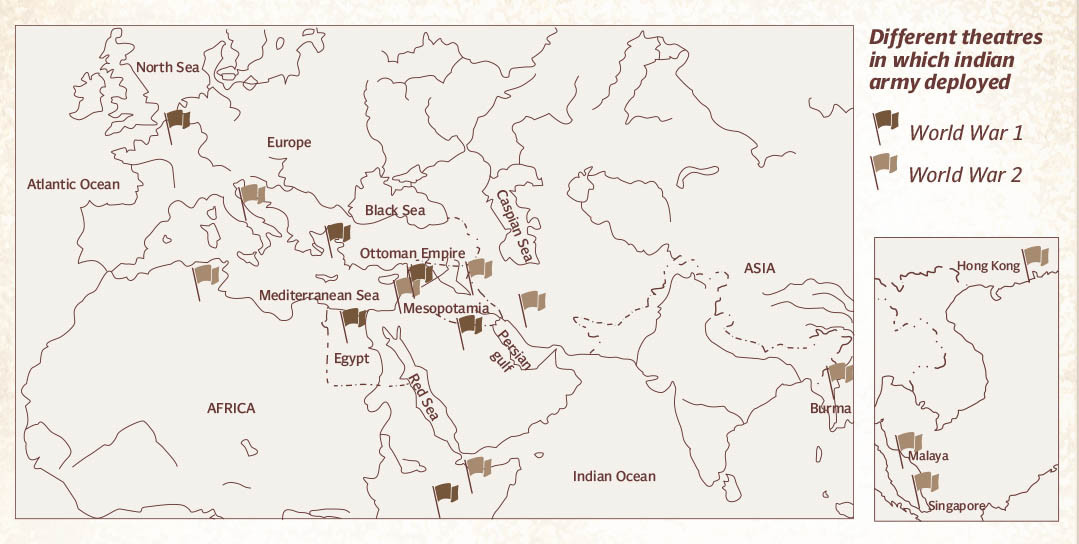

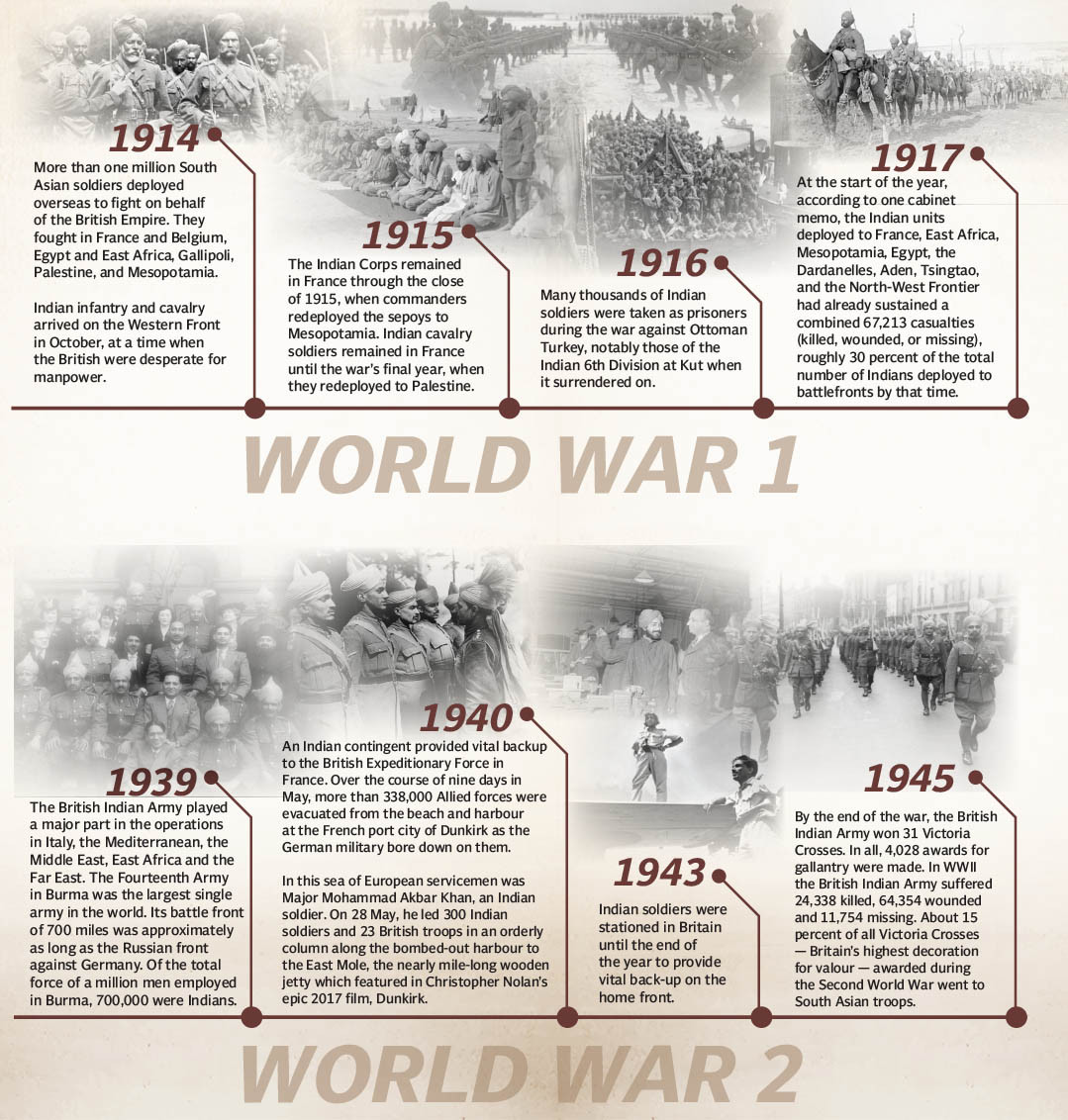

Over 1.5 million troops from the Subcontinent served overseas in various theatres of the Great War – from Europe to the Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa. At least 74, 187 of them died during the war and another roughly 67,000 were recorded to have been injured.

The number of South Asian participants in the next great war was nearly double. Rising to more than 2.5 million men in August 1945, the force would become the largest volunteer army in history by the end of the Second World War. The British Indian Army made several notable contributions to the Mediterranean, Middle East and African theatres in World War II. In North Africa, it participated in the Compass, Battleaxe and Crusader operations as well the first and second battles of El Alamein.

The force also participated in the Italian campaign as well as the campaign in Burma.

Speaking to The Express Tribune about the participation of South Asian troops, military historian Maj Gen (retd) Syed Ali Hamid said there were no Indian officers in the First World War. “The exceptional figures were the soldiers who were awarded the Victoria Cross and their actions are well recorded.”

“In the Second World War, Indian officers were also awarded for gallantry alongside soldiers,” he added. “Some of the Indian battalions and brigades did perform exceptionally well in Eritrea, North Africa, Italy and Burma. There were of course many acts of individual gallantry by the Indians from sepoys upwards including a number of them who were awarded VCs. Some acts of gallantry may not have been recognised but it would be difficult to identify such individuals.”

According to Gen Hamid, while Indian officers were gradually replacing the British throughout the Second World War, British officers by and large provided the leadership. “Additionally except for the final stages of the Burma campaign, when some of the infantry brigades had all three battalions of South Asian soldiers, Indian infantry brigades normally had a mix of one British and two Indian battalions.”

Tales of valour

Sharing some of the tales of notable individual contributions to the First Second World Wars, he spoke about the small village of Panjeri on the southern edges of the Pir Panjal Range between the rivers Jhelum and Chenab. “The village may seem little different to others in the same region, but it is unique in that this one village was the birthplace of four Viceroy Commissioned Officers (VCOs) who were awarded the Military Cross (MC) during the two World Wars,” he shared.

The first of these VCOs was Risaldar Major Farman Ali, who served in the Burma Mounted Rifles (BMR), which operated in southern Persia from 1917 to 1919. During this time, Farman was recommended for an Indian Order of Merit twice but the award was reduced on both occasions to an Indian Distinguished Service Medal (IDSM), Gen Hamid said. “It is therefore befitting that he was ultimately awarded a MC in 1919, for ‘Distinguished services rendered in connection with the military operations in the North West Frontier, India, in Persia and Trans-Caspia’.”

The other three VCOs – Subedar Ghulam Rasul, Subedar Fazal Dad Khan and Jemadar Fazal Dad – received MCs during the Second World War. “Subedar Ghulam Rasul was commanding an infantry company of the 4th Battalion (Bhopal), 16th Punjab Regiment known as the ‘Bopees’ during Operation COMPASS against Italian forces in Libya in 1941,” Gen Hamid shared. “The battalion attacked a strongly entrenched Italian force, on four concurrent nights. In all four, Ghulam Rasul led the company ‘with great dash and gallantry under heavy MG and mortar fire’ and under his leadership, the company also successfully beat back a determined counter attack that posed a serious threat to the battalion’s flank,” he added.

Speaking about Jemadar Fazal Dad, Gen Hamid said he earned the MC in Italy in 1945 while commanding a troop of armoured cars of 6th Lancers, the reconnaissance regiment with the 8 Indian Division. “The division was racing through the valley of the River Po in the last stages of the Italian Campaign and Fazal Dad’s squadron was leading one of the infantry brigades. When his troop approached a large canal it came under heavy fire,” he narrated. “On the Germans’ side, the end span of a wooden bridge was aflame but in spite of the enemy’s fire, under Fazal Dad’s guidance, his troop dampened out the flames and held the bridge for the next eight hours.”

A few kilometres from Panjeri, the village of Chappran is home to another MC recipient, Jemadar Hakim Ali, Gen Hamid said. “He was serving in the 6th (Jacob’s) Battery, 21st Indian Light Mountain Regiment which was supporting 17 Indian Division in Burma in 1944. While marching through the dense jungle the battery lost contact with two platoons that were escorting it and were ambushed close to dawn,” he told The Express Tribune. According to the military historian, the first volley left the battery’s Subedar Major seriously wounded and Hakim Ali in charge of the guns. “Wounded himself, Hakim got the guns into action and his well-sited local protection parties drove off repeated enemy attempts to attack the guns. His citation states the ‘his coolness and fine example to his men undoubtedly saved the Battery from what might have easily led to almost complete annihilation.”

On the Eastern Front, Gen Hamid also shared the story of Lt Syed Ghaffar Mehdi, whose feats during the British Indian Army’s campaign in Burma earned him the nickname ‘Killer’ Mehdi. “On the night of April 2, Lt Mehdi was leading a small recce patrol. Finding strong evidence of Japanese presence, he probed further and clashed with a Japanese patrol,” he said.

According to Gen Hamid, there are two accounts of what ensued: “Lt Mehdi’s citation states that when the scouts gave a warning of the approach of the Japanese, the officer set up an ambush and having allowed two enemy scouts to pass only 12 yards away, opened fire on the main body. It credits Mehdi with personally killing five of the seven Japanese.” The other account, narrated to Gen Hamid by Lt Mehdi’s son based on Lt Mehdi’s own version of events, purports that there was no planned ambush but a clash with a Japanese patrol in which both sides were equally surprised and opened fire as they hit the ground. “When the firing subsided, Mehdi found he was all alone. Ignoring a call to surrender, he surprised the Japanese from an unexpected direction and killed all ten of them,” he added.

Gen Hamid also shared the experience of Lt Col Mohammad Mohyuddin Siddique Raja MC (Bar) who, as a lieutenant posted to the 4/13th Sikh Regiment, fought the Italian Army's specialist mountain infantry of the 1st Alpini Battalion, 10th Savoy Grenadier Regiment, in Eritrea. “The 4/11th Sikh was tasked with capturing the three peaks of Mount Samanna, named left, center and right bumps. Lt Siddique commanded the leading company tasked with capturing the Left Bump,” Gen Hamid said. Lt Siddique led the company into the attack under heavy small arms, machine gun and mortar fire, sustaining comparatively light casualties. Under heavy fire, he also consolidated the defence and provided support to the companies attacking the other two peaks. “Siddique also replaced an injured company commander to lead that company on a night attack on Middle Bump. He was wounded twice in this action,” Gen Hamid added.

The captive experience in Europe

In addition to the 87,000 soldiers, air crew and mariners who either lost their lives or were reported missing in action in World War II, as many 79,489 South Asian personnel were taken as prisoners of war. While most of them – around 60,000 – were taken at the Fall of Singapore by Japanese forces, a significant number – between 15,000 to 17,000 – were taken by either German or Italian forces.

Speaking to The Express Tribune, Professor Ghee Bowman, a historian and author focusing on both World Wars, described the conditions the men who were taken captive faced. According to him, there were at one point as many as 15,000 Indian prisoners of war in Europe.

“Most of them were taken in North Africa by both Germans and Italians and came from a wide spread of backgrounds: Punjabi Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Christians, Ghurkas,” he shared. “There were even some from before that who were taken prisoner in East Africa.”

Prof Bowman said that these men were initially held in what were described as ‘cages’ in North Africa. “Some of these were in extremely bad condition and really quite primitive. And then they were taken by ship to Italy, where they had some famous camps. In fact they had a POW camp that was just for Indians.”

“Additionally, there’s also the smaller story of the 320 men of the 22nd Animal Transport Company of the Royal Indian Army Service Corp who were taken prisoner in France in the summer of 1940 and were the first Indian POWs taken by the Germans,” he said. “They were prisoners of war for nearly five years so that’s a very kind of substantial period of time.”

According to Prof Bowman, when the Italians surrendered and capitulated in September 1943, there was a period of uncertainty about all of the commonwealth prisoners of war in Italy. “In some cases, the POWs ran into the hills. In others, they were told by the British army to stay where they were and in a lot of cases they did,” he said. “A lot of them were taken by train across the Brenner Pass between Austria and Italy and in to Germany. Subsequently, they were spread around Germany, Austria, Poland, France – across the German empire of the time.”

Officers, sepoys and in-between

One of the interesting things about the camps in Europe, he said, was a division between officers and other ranks. This, he highlighted, posed an interesting issue in the case of the British Indian Army. “In the Indian army at the time, you had these VCOs (Viceroy Commissioned Officers). They were in a rather unusual position in that they weren’t seen as being officers like majors and captains, but neither were they non-commissioned officers like sergeants. So they were actually sort of in between,” he pointed out.

According to Prof Bowman, what the British officers did was to say the VCOs are officers and therefore should be in the officers’ camp. “That meant the VCOs had better conditions.”

He mentioned that one of the experiences most South Asian POWs in World War II faced was that they were moved several times between different camps. “This is one of the features … they weren’t in one camp for a lot of years. They were in lots of different camps.”

Prof Bowman also noted that there were a number of Indian commissioned officers in the prison camps in Italy as well, such as Anis Ahmed Khan. “He was the first Indian officer to be captured in the war and spent nearly five years in prisoner of war camps,” he mentioned. “After the war, he had an interesting trajectory in that he was a Muslim but decided to stay in India and went on to become a very senior officer in the Indian army but subsequently, he changed his mind and actually lived the last few years of his life in Pakistan.” According to Prof Bowman, Capt Anis was promoted to major during his time in captivity.

Complicated hierarchies

According to Prof Bowman, South Asian prisoners of war in Europe were kept together in most cases, but he pointed to an interesting facet in terms of hierarchy. In both Britain at the time and the Indian Subcontinent, there existed a class hierarchy that was often linked to education and social classes, he said. “Then you have ranks within the army, and those are very clear, complicated by VCOs, not understood by British or Germans, Italians,” he pointed out. “Then you have this whole Indian idea of caste, and class in how the Indian army was recruited. That kind of comes through.”

“And within that, every Indian POW camp we have looked at records from there is a group of Muslims that is together and there are Sikhs who are together and a group of Gurkhas who are together, etc.,” he added. “They’re cooking for themselves and they’re looking after themselves, praying together. There are photos of Muslim prayer rooms and Sikh gurdwaras in the camps.”

Prof Bowman noted that on top of these various social and religious hierarchies, the POWs had the German and British racial hierarchy. “It’s particularly interesting in the case of Germany because the German Reich is built around racism. It’s built around the idea that some races are better than others. ‘Aryan’ people are at top of that hierarchy and at the bottom of that hierarchy are the Jews and black people.”

According to Prof Bowman, British prisoners of war were treated reasonably well. “And generally speaking, Indians were considered to be part of more or less the same thing as British by the Germans. At least officially speaking they were treated the same way as white British prisoners of war.”

He added that what complicated this further was the whole German idea of the Aryan race which said that there was a strong link between Germans and the people particularly from the north of India. “An entire branch of German pseudoscience sought to prove they were actually the same race,” he said. “So it’s an extraordinarily complex picture of hierarchies among prisoners.”

Maj Gen Syed Ali Hamid, however, disputed the idea that South Asian POWs were treated well, although he did say the conditions in camps in Europe was much better than in those run by the Japanese. “In general, the experience as POWs was very different with the Japanese and the Germans and Italians. The death rate of POWs held in the West was four per cent. For those held in the East, it rose to 25 per cent,” he said. “How many Indians actually died I wouldn’t know … but a couple of Red Cross reports that I have read of camps that had Indian as well as European POWs, there was no mention that the Indians were treated any better than the others,” he said.

A historical challenge

One of the biggest challenges with research around South Asian participants of the first and second world wars is that much of the written evidence is in British archives, Prof Bowman said. “The records are either from British officers or it’s these memoirs from officers in the Indian army who went on to become quite senior officers in the Pakistan or the Indian army,” he pointed out. “There are very few stories from sepoys and other common men on the ground.”

Prof Bowman said he did make a trip to Pakistan in 2018 with the aim of getting into local archives. “I didn’t manage to do that but I went to villages in Punjab and met children and grandchildren of ordinary soldiers.”

“It was remarkable how little they knew and this I think is one of the key points that I’m reminded of,” he noted. “From a British perspective… it is very standard for the families of these ordinary soldiers or sailors to have physical stuff or photos, possibly little memoirs and letters. In my experience in going around villages in Punjab, that’s rarely the case. People will have a tiny fragment of a memory… they would know that my grandfather was in a camp and treated badly but that’s all.”