The show titled ‘Fixed Price’ explored the nexus of aesthetics and the market forces. Art is a nebulous area, an area where logos drops and imagery takes over. What can be vague or sensed ideas, feelings hard to describe and put into words, are taken by the artist and visual imagery created. Disturbance and discontent brewing under the social fabric is picked up and conveyed visually in a form hard miss or ignore.

‘Fixed Price’ the first exhibition curated by the Abid Aziz Merchant the co-founder of Sanat Initiative featured the work of Adeeluz Zafar, Meher Afroze, Muhammad Zeeshan, R M Naeem and Scherezade Junejo, and reflected on the last eight years operating a commercial gallery in Pakistan, with all the variable and uncertain market forces, while building a diverse and vast network of relationships with artists and collectors. The show investigates the impact and implications on what it may mean to hold this important node as a constant and important infrastructure of support in the art world.

Adeeluz Zafar’s work on display featured his soft toys in bandages. Intricately crafted black and white, etching on photographic paper. This is a motif he has been exploring for some time. Two pieces were prints, one unmistakably Mickey Mouse and the other Bugs Bunny, both animated by humour, although wrapped up in bandages one could not miss the provocative stance of Bugs B and the head tilt and hand gestures of the affable Mouse. It is fascinating that these characters seem to be ageless and what one saw in childhood is so deeply engraved that one can recognize it even when the entire form is covered up. A form or character/s that are eternally upbeat, even in the face of defeat they recover, indefatigable and on the quest. At 93 years of age, Mickey Mouse is a character spanning multi generations and is a global icon. Rendered in Adeel’s dark monochrome with gapping areas of darkness where the bandaging sags, the image invites rather evokes a deeper response. Behind Mickey’s smile and Bugs’ cockiness seems to lie the Capitalist narrative, the promise of hard work and reward, yet a deeply hierarchical system characterized by intense competition, a narrative introduced to pre verbal stage children who learn the inherent violence of divisiveness instead of the nurturing and nourishing bonds of inclusivity and unity. And there in the soft warmth of children’s soft toys lies another narrative, one not so soft or nurturing.

Mehr Afroze’s work is informed by her cultural past rooted in Lucknow, although Karachi has been her home. In this divide of roots lying in a different cultural context and a home that is in a commercial hub of the country lies her exploration and work. An extensive exploration into the reclamation of a lost past aptly titled ‘Azmaaish’. Sensitive, delicate and rhythmic, her imagery conveyed nuanced harmony that pulled the viewer into the work, landscapes of earth tones and blues, a repeat pattern the eye grazed over and there imbedded in a tiny square in each work was a word. ‘Ehed’ in one and ‘eeman’ in the other. The meaning of ‘ehed’ is a promise, an allegiance and its flip side is accountability. Whether a promise is kept or not, it is embodied within accountability. The act of a promise, is an act of accountability yet the urdu word ‘ehed’ embodies both words of promise and accountability, the connotative conveyance of accountability bolder than the promise as the ‘ehed’ is given in a culture which held self-respect synonymous with fulfilling an ‘ehed’. And the inability to fulfill an ‘ehed’ meant the loss of self-respect, a reference to a lost past where one’s honour was one’s word. A past where such values were upheld. In that one word is what the values that were part of an East where Mehr Afroze comes from, were embodied. She references a lost past, a heritage that a fledgling country, a break away piece from the whole could not and has not been able to maintain. Struggling with economic and political instability, it has not been able to hold soft power, the ability to hold its heritage. Yet it’s not a country that holds an ‘ehed’, it is each individual. In her landscape of blues, embedded within a small square is the word ‘eman’. In a landscape of indigo blues devoid of any other visual reference, held in place by fine rhythmic geometric patterns, the word ‘eman’ – faith – seems to be self -referenced, rather than a faith referenced by any religious format or creed. Implying a faith one has within oneself, a faith in a higher power of creation, that enables courage and the ability to create and to deliver of oneself, of ones’ promise. And perhaps in a struggling fledgling country, the stability will come from this ‘eman’ and each individual’s ‘ehed’. It may be an ‘Azmaaish’ but perhaps with a deliverance.

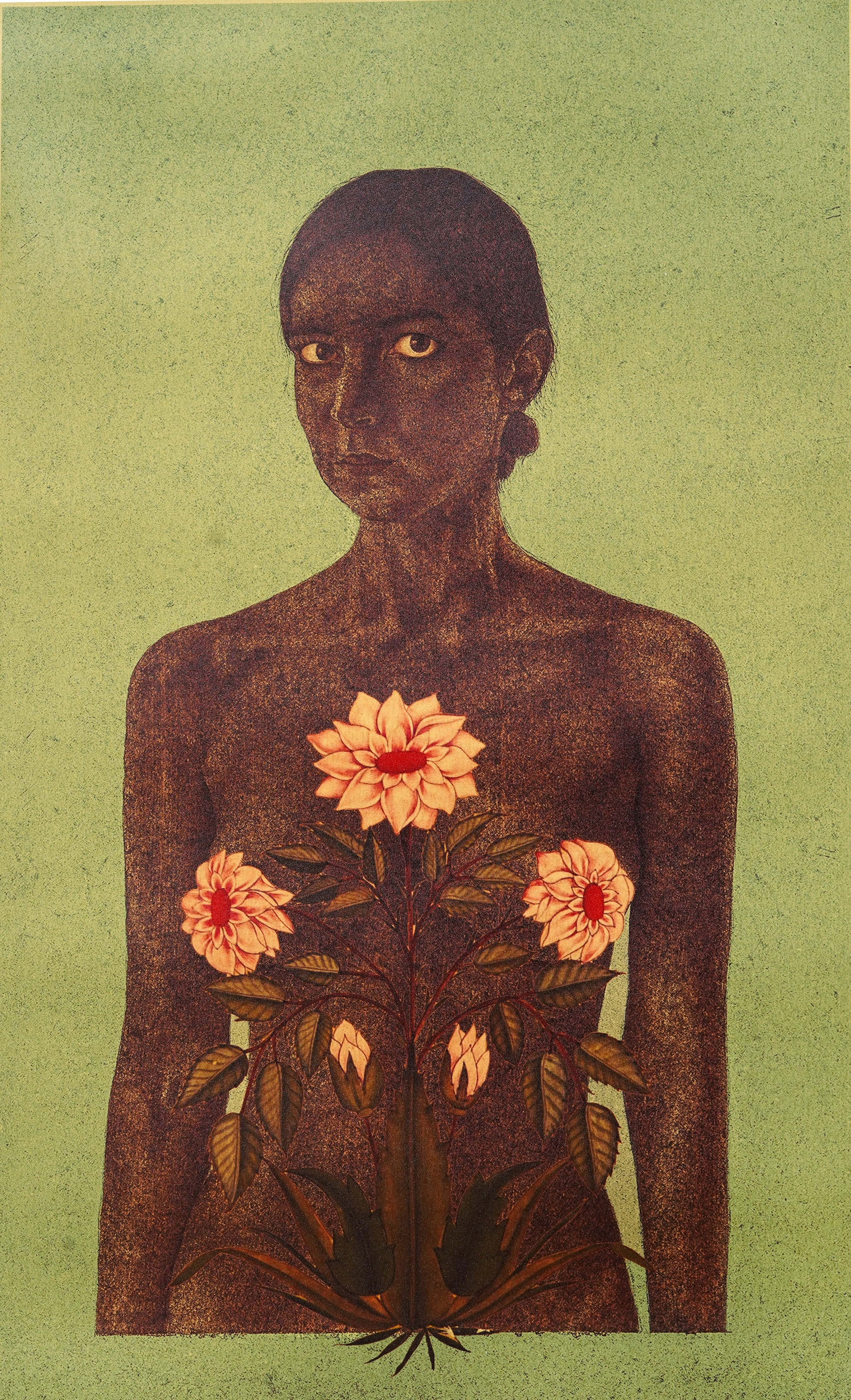

Muhammad Zeeshan’s work is informed by his early training as a commercial painter at the age of fourteen for cinema hoardings. A graduate of the prestigious National College of Arts, his imagery has evolved and on display were dark, beautiful women, self-reflecting. The women spanned a century from the early 1900’s to mid-century to the current point. Done on sandpaper with a flat backdrop of colour, providing a prominence to the quiet of the women as they gazed into mid distance. Nangeli with her arm raised, chest uncovered and partially covered with a sari referenced the tax women of a certain caste in Kerala had to pay over three hundred years ago if they wanted to cover their chest. It has it said that Nangeli, a young Ezhava woman from Cherthala, frustrated by this indignity, cut off both her breasts instead of handing the tax to the tax collector. She did not survive, but her act of defiance has now come to be a symbol of resistance to this practice.

Muhammad Zeeshan recalls his young days when he was required to paint black cross hashes over exposed flesh or cleavage of a woman on the hoardings as part of the compliance to State censorship. His quiet, sensitive series of nudes spanning more than a century had one thing in common: the lack of body autonomy, from the crude brute force meted out to Nangeli and her caste women, to State censorship to social norms. The disquiet of the women in his work seemed to summate the experience of autonomy or the lack thereof women have faced.

R M Naeem’s sensitive figurative works seem to have honed one thing – feelings of interiority within a fully embodied human form. His large landscapes in black and white were explorations. Against a layered backdrop of porous rectangle-scapes was a constant atmospheric quality of rain, of a cloudburst connecting the sky to the earth. In the foreground, a woman, solid yet soft, in her reality, as a slightly plump woman seeming to hang laundry with a child, or a child like doll replete with baby folds. In another a younger woman, in tights and a cami and a hasty topknot kneeling in what seemed to be in prayer over a spot lit area of organic growth, dispersed and suggestive. She held an offering of a few stems, head down bent. In another a young woman, with more gumption seemed to stand in a room in profile, arm upheld, the hand in finger gun mode and floating on top, almost in flight the cherubic baby doll. These diverse women of differing socioeconomic status displayed the same sense of interiority, the same space of self -reflection, the same quality when faced with an obstacle. These women in R.M Naeem’s almost surreal backdrops seemed to be ruminating a future, or present or lack thereof. With society rigged by it’s social, cultural and religious norms what are the choices women face, or is ‘choice ‘ too generous a word to use for women in this social set-up.

Polished and visceral, Scherezade Junejo explored a repeat theme, Woman. Beautifully crafted, the imagery meant to provoke. Red, deeply creased sheets torn mid canvas as though paper and in between the two a peeping organic form, peaking limbs, just the tip of toes softly curling into the sole of the foot, as though in relaxation and abandonment of sleep or pleasure. Although the form used by her is a woman, it’s in the form of statues of classic antiquity, missing head, arms and legs, and seemingly only the torso is visible. Of course it’s hard to miss a frontal nude form but even when it’s the back, it’s unmistakably a woman. Pink with grey shiny heart shaped balloons, with a perky graphic illustrative quality, the painful arch of the shoulders, in withdrawal, in confusion, in shame and the emaciated rib cage. The objectification sold to us and the embodied pain of the women used for marketing the Capitalist goods of the West, for consumerism, at the expense of humanity. Perhaps the most violent illustration of this objectification was in Scherezade’s last canvas, a bold layout of three nudes, shoulders thrown back, tilted hips, arched back, legs in defiant akimbo. Perhaps only a woman can paint something so inherently violent, women defined by the male gaze, objectified with commodities, glamourized on run ways, by fashion houses, by the glossies, their humanity lost, a mere sham of flesh for products, to maintain an artificial demand, to maintain the hierarchy. The slick, polished style of these nudes, beautified in every way was too close to home, an image and aesthetic pervasive on every social media platform, every mothers exoneration ‘smile’, The misogyny sold commercially and culturally, the violence that women are supposedly meant to internalize. The plastic culture that commodifies a woman’s humanity, for purposes other than serve her, is unforgivably explored and portrayed by Scherezade.

The exhibition was sensitive and bold and nuanced. The market can lay a price, but the valuation of art that holds up a mirror to society, how do you value that.

Asma Ahmad is a freelance writer. All information and facts provided are the sole responsibility of the writer. The exhibition ‘Fixed Price’ curated by Sanat Initiative was held from August 2 to 11, 2022