In a country that has its healthcare, in many ways, in shambles, and its citizens do not rely on public health care due to inadequate attention from health care providers, what is the motivational aspect that is bringing back people who live abroad to come to Pakistan and get their treatments and surgeries done in Pakistan? In recent times, a surge has been seen in people’s visits to Pakistan for medical tourism.

Pakistan is ranked 122nd out of 190 countries in the World Health Organisation performance report. Pakistan ranks 154th among 195 countries in terms of quality and accessibility of healthcare. And even then, if we see people believing in our doctors for a quality treatment, it is nothing less than a miracle.

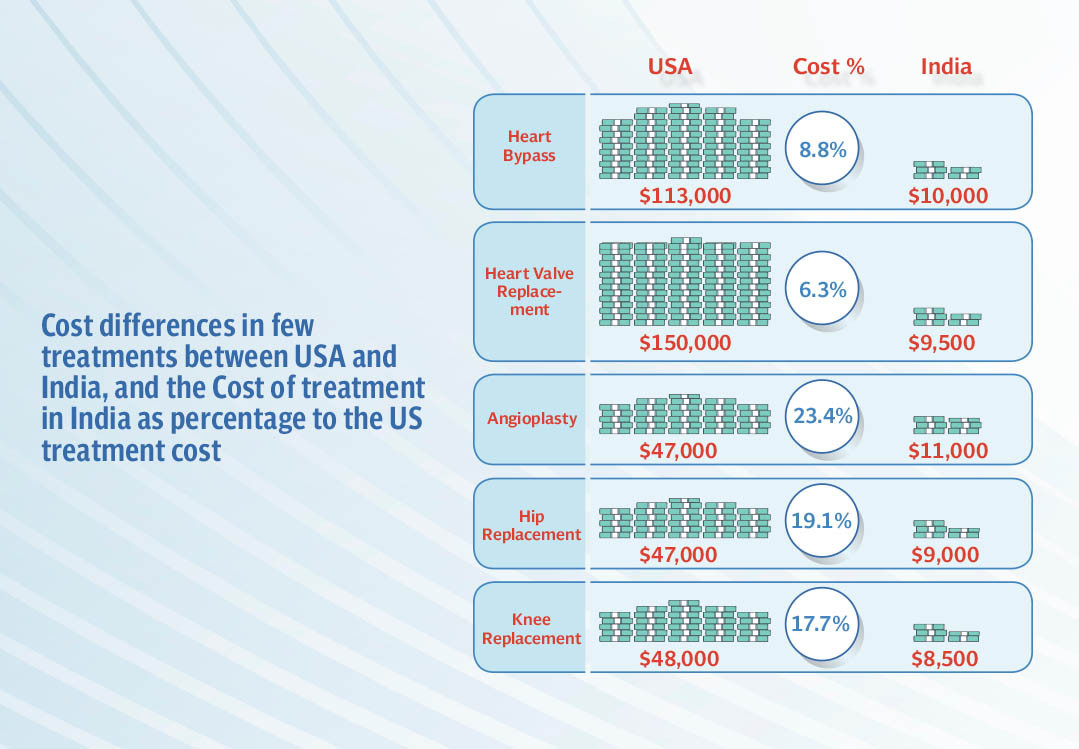

Pakistanis living in the Gulf region or other developed countries, such as the USA and the UK, sometimes travel back to their home country to get medical treatments. Various reasons are factored in. One reason is that the waiting list in their second country is very long, and sometimes they have to wait for months, or even years, to have their surgeries done. Secondly, in most of the countries, health care is extremely expensive. Another reason why many people come to have their medical treatments done in Pakistan is because they have their families here and can get moral support from their parents, siblings, or relatives. Most of these people only opt for the private health care system, but in recent times, we have also seen some surgeries performed in public facilities. Such cases are not very common but not very rare either.

Bone marrow transplant

In 2019, when Rabia* got married to her first cousin, she never thought that just after a year she would be celebrating her anniversary in a hospital isolation ward. “It’s been almost two and a half years that we have been married but we have not celebrated anything all this time, not the birth of our son or our anniversaries.” Rabia shared that their son, Syed Muhammad Qasim, was diagnosed with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) at the time of his birth. SCID belongs to a group of rare disorders caused by mutations in different genes involved in the development and function of infection-fighting immune cells. Infants with this disease appear healthy at birth but are highly susceptible to severe infections. Qasim was diagnosed with the most severe and rare form of SCID—reticular dysgenesis.

The couple live in Abu Dhabi due to Rabia’s husband’s job requirements. Her pregnancy went very smoothly, and she didn’t face any complications. But in her thirty-seventh week, her doctor suggested doing a caesarean operation because the baby was underweight; her placenta was not providing proper food. “Just because my son was underweight, he was put in NICU and they ran some tests, which indicated a lower number of white blood cells. As we were alarmed, the doctors ran more tests, or we would have never known that he had SCID,” she shared how running some minor tests can help save a life.

Despite being a mother for weeks, Rabia couldn’t touch or even hold her baby Qasim because his white blood cells (WBC) were 0.06 percent, very low for his age. “We kept shifting him from one hospital to another for better facilities for his case; many doctors suggested boosters of WBC to help sustain him, but the biopsy report after forty days of his birth made my son’s condition quite clear. We wanted a permanent solution, and after several opinions from different doctors and through research, we found out that only a bone marrow transplant was the solution to Qasim’s problem,” Rabia explained.

The whole of Abu Dhabi didn’t have any bone marrow transplant facility available at that time. Now there is a centre, but it will still take a few more years to have facilities for the transplant that was needed for Qasim. Rabia and her husband remember how they could only see their firstborn wearing masks, gloves, and PPE, as it was 2020 and the peak of COVID-19 restrictions. “After realising the severity of our child’s condition, we instantly decided that we will get the transplant done, and as both my family and in-laws were in Pakistan, it was the best and the safest option for us,” Rabia said. They had two options—the Combined Military Hospital, Rawalpindi, and the National Institute of Blood Diseases, Karachi. “We sent all the reports to Pakistan, my father consulted Dr Tahir Shamsi, and we were told that as soon as we landed in Pakistan, he would start the procedure of Qasim’s treatment,” Rabia added.

Being a mother with a three-month-old child it was difficult for Rabia to gather herself and decide so many things, fully aware how in Pakistan everyone tries to intervene. “From the airport, we took Qasim straight to the hospital, and within three-four hours, all his pre-surgery blood tests were done. His father’s HLA typing matched—he was his donor. NIBD handled everything very well,” she said with a satisfied smile on her face.

Two of the main reasons why people come to Pakistan for treatment is post-care and moral support from family, and that was also the case with Rabia. After the transplant, Rabia and Qasim had to isolate for fifty days without any contact with germs and life outside a room, extreme precautionary measures. Rabia says, “It was a very difficult time as my husband had to fly back to Abu Dhabi; but my family and in-laws stood by me like a rock during that time. That was something I would not have had if I had not been in Pakistan.”

Facilities that Pakistan offers in terms of health care are phenomenal when it comes to private hospitals, but the same cannot be said for government-run hospitals. The trust people have is for private facilities. “We were very sceptical about doctors in Pakistan, and personally, we would have not come here if Abu Dhabi had a transplant facility available. But as the best option was Pakistan, and doctors here proved me wrong, I am happy that we took that decision.” Rabia’s son is healthy now, and his regular check-ups are showing improvement in his condition.

The entire transplant was estimated at PKR 4.5 million but was done in 3.5 million. “We had to submit the full amount before the procedure started, but after the treatment, the remaining amount, around PKR 800,000, was returned to us,” Rabia shared, adding that the CMH gave an estimate of around PKR 5.4 million. It may seem like a huge amount, but the treatment in Abu Dhabi is even more expensive; a single injection that is administered to Qasim every month costs around AED 800, approximately PKR 45,000, which her husband’s office covers in his family medical insurance. Qasim’s monthly medicines cost around AED 2,500. “Getting him treated in Pakistan had its pros and cons, but yes, the doctors were thorough professionals, and I had my family by my side, which helped me so much in my difficult time,” Rabia added.

Post care and waiting

Belief and fear attached to health care plays a vital role when it comes to treatments. People mostly travel to get surgeries done because they think waiting might prove fatal. Fabiha Zeeshan is the mother of an eight-year-old and travelled to Pakistan from the UK for fifteen days just to get her surgery done. “In the UK, I was consulting my general physician, but he was unable to diagnose what exactly the problem was. He kept giving me medicines, and I kept going back to him with the same complaint. It went on for almost two years when I was diagnosed with a fibroids issue,” Fabiha says. Fibroids were causing several problems in her daily life, but the doctor in the UK didn’t seem very serious about performing a surgery.

For most people, getting second opinions and asking family for help are the initial responses during an illness, and Fabiha did the same thing. “I was discussing the issue and my frustration with my mother when she suggested to me to consider having my surgery done in Pakistan. The idea was vague at first, but when I started online consultation, I didn’t take long to decide.” Rabia added that on the fifth day after her flight, her surgery was conducted in Saifee Hospital, Karachi, and after ten days, she flew back to the UK. “The cost for a private facility in the UK would have cost me much more than what it cost me to come to Pakistan, get treated, and even see my family.”

Ayesha*, another expatriate diagnosed with fibroids, knew exactly what she had to do. “I knew I would get my surgery done from Pakistan as I need my mother by my side no matter what. The waiting list was a factor, but more than that, post-care and family is what mattered to me,” she told me.

Ayesha, despite having a history of endometriosis and other related diseases, was sure about the treatment she wanted and from where she would get it. The only fearful thing was that she didn’t want to wait long, as fibroids affect other organs, and in many cases, intestines, and in some cases, kidneys. Ayesha was clear in her mind about coming to Pakistan and get her surgery done at the earliest. She shared with me how Dr Rubina Hussain operated on her within a week, and as she had her mother and siblings by her side, it was easier for her to recover soon.

Government’s role

Expatriates or dual nationality holders coming to Pakistan to get their treatments done is a positive image of the country but spending taxpayers’ money and use of facilities for any patient who is treated in a public hospital cannot be sustained on a long-term basis. “We are in talks with government; we plan to regulate the system and set a minimal amount for the treatment of patients visiting from other countries. No one will be treated free of cost,” Parliamentary Health Secretary Qasim Soomro said. He was talking about a woman who recently arrived from the USA to have her transplant from the Gambat Institute of Medical Sciences. After that case, many questions were raised as to why and how a US national was provided free treatment while many Pakistani nationals are on a waiting list. The reason cited was her condition and promotion of medical tourism in the country.

Soomro said, “We can’t spend taxpayers’ money like that; it is a high-end facility, and we have to regulate it so that it can be more effective for our people.” He added that if numbers are taken into consideration, government facilities do not have a definite number for medical tourism. Keeping a track becomes a problem as it is hard to prove whether the patient is a local or a Pakistani residing in any other country.

Many instances have been reported where people visiting from Europe, USA, or the UK, for winter holidays or to see their families in the interior parts of Sindh, get their various medical procedures done from the Gambat institute. After the belated realisation of the importance of the institute’s high-end facilities, Sindh’s chief minister has decided to declare it a medical city. “The plan is to extend the link to Mohenjo Daro and Sukkur; if medical tourism increases, government must increase facilities of travel and accommodation for patients,” Soomro said. He added that a detailed plan is expected to be out by August, and initial work has already been started.

The reality is perplexing. People are visiting Pakistan for treatment in private facilities, but government is unable to maintain a record as it is difficult to differentiate between a mere visitor or a patient arriving for a surgery.