Identification is the most important part of anyone’s personality. One’s name helps them stand out from others and get recognized by states and other institutions. But what happens if someone can’t get their identity registered or is denied a national identity card?

This is a question faced by millions in Pakistan, including Afghan refugees, undocumented immigrants, and countless others who struggle to produce the paperwork needed to satisfy the requirements of the bureaucracy. Without a computerized national identity card (CNIC) managing one’s life isn’t easy; this little card is necessary for everything from getting a job to an education, healthcare, and welfare.

The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) was created to help keep track of people’s identities, providing them with a unique CNIC number so they can avail the services they are afforded as citizens of Pakistan. But many people in the country can’t get a CNIC made. Their stories speak to a system burdened by inefficiencies and corruption, in which people spend years trying to get simple documents.

Alone in the world

When Sheeba was a child, she remembers roaming the streets by herself to look for food, one day ending up at the gate of a house where the family took her in, providing her food and shelter. Sheeba, now 45, used to help the mother of the house, who she calls Ammi with daily chores. Without any other family in the world, this woman showed Sheeba what it meant to be taken care of and provided shelter, food, and clothes.

Sheeba’s Ammi arranged for her marriage with someone from a similar situation, but he died of tuberculosis soon after, leaving behind Sheeba and her three sons. Although Sheeba’s caretaker provided her with the material things she needed, she never realized the importance of documentation, so she didn’t get Sheeba’s paperwork done.

Her caretaker died soon after Sheeba’s husband did, leaving her along with no proof of existence. Without a CNIC or any proof of identity, Sheeba said her sons, ages 10 and 11, are suffering. They can’t appear for matric exams since they don’t have a B-form, for which CNIC is required. Without a CNIC, Sheeba doesn’t know what will become of her children. “I fear they will face the same fate as mine,” she said.

Sheeba said she tried many times to get a CNIC made but is continually told by NADRA officers that she needs certain documents for proof – documents she doesn’t have. Although Sheeba’s situation being without any family members is rare, her struggles are not unique, as many others have had to go through NADRA hurdles – from visiting centers multiple times to being asked for bribes -- to get a CNIC made.

Differently abled

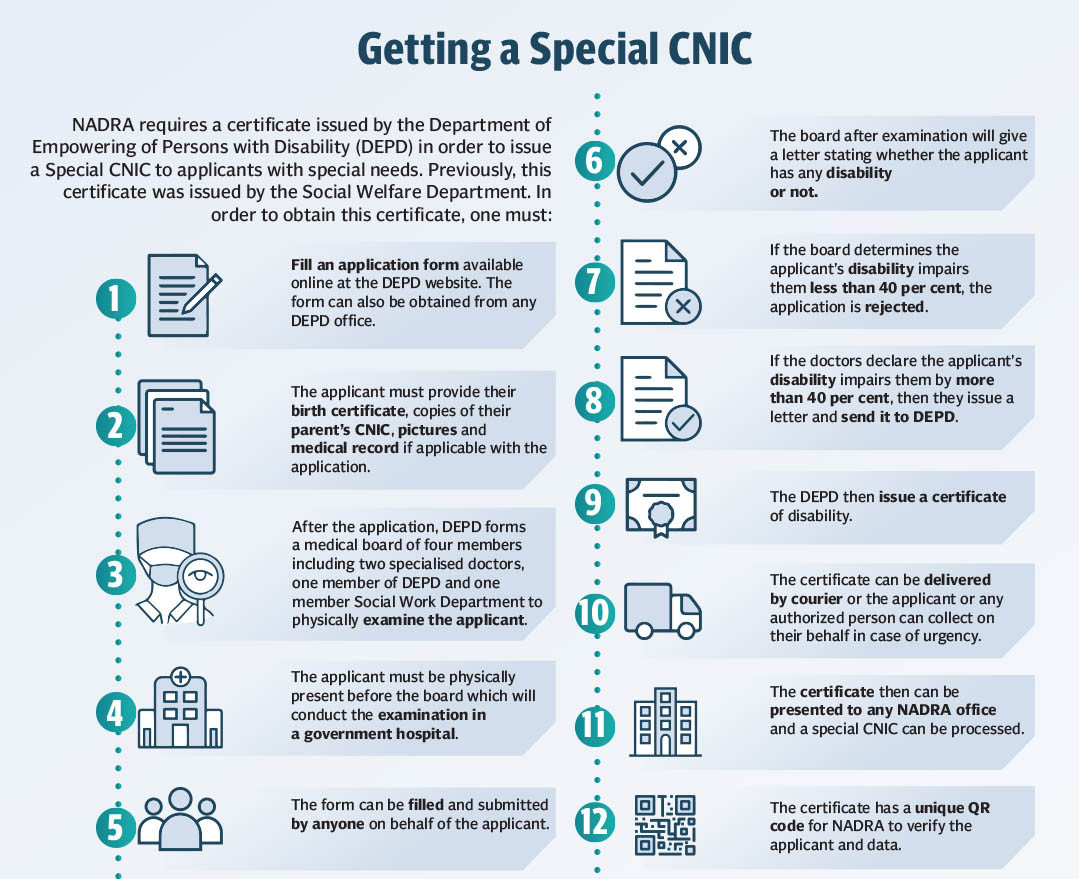

The process of getting an identification card is easier for differently abled citizens than it was for Sheeba, but it can still be a lengthy process. Amna Raheel, who is wheelchair bound, said her family didn’t try to get a special CNIC made to acknowledge her muscular dystrophy because they knew it would take several visits, and maybe bribes to get it done. Instead, her father, who had a connection in NADRA, was able to get her a normal CNIC. But there are also differently-abled people who want to get special CNICs made because they give governmental benefits but they have to jump through hoops to get them.

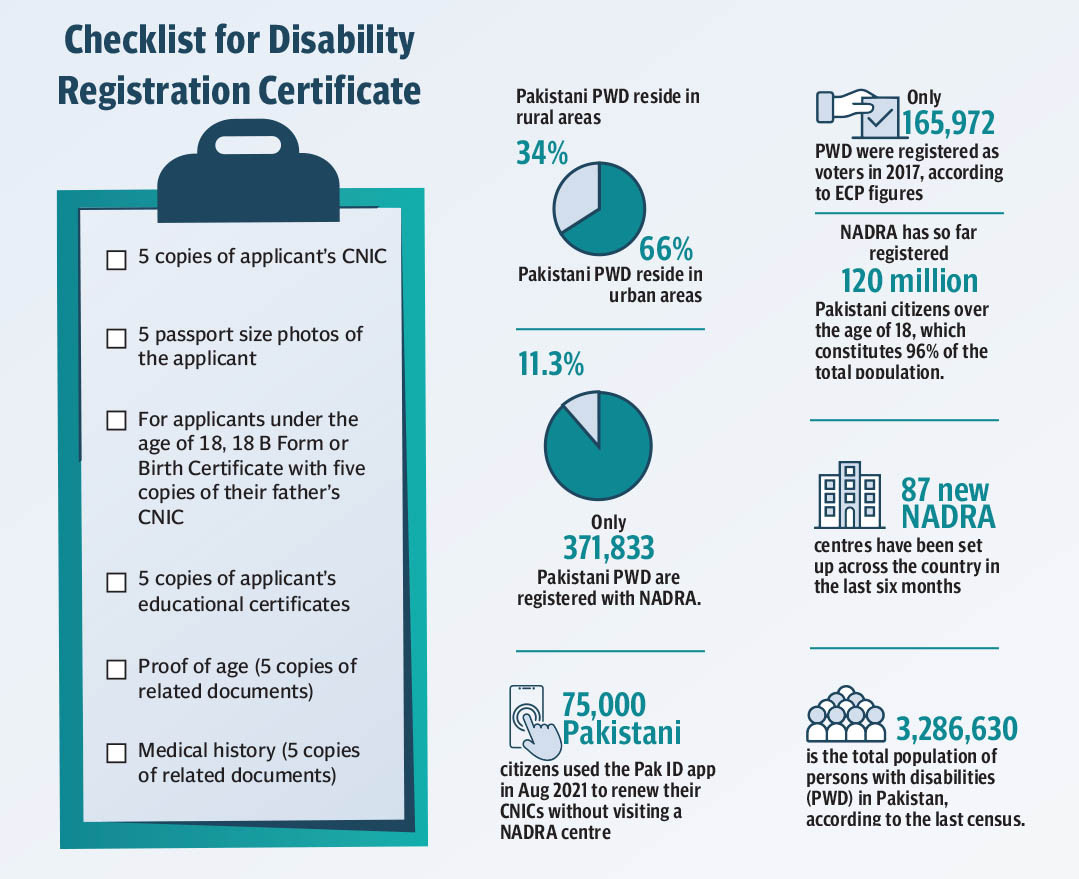

NADRA has been very clear guidelines for its procedures but the process in person is not so simple. To get a certificate from the Social Welfare Department, differently abled people also need to get a letter from a government hospital declaring them differently-abled.

Hospitals have teams of doctors to physically examine applicants and verify their condition, before issuing a letter from which they can get another letter from the social welfare department. The team at the hospital consists of two doctors, a member of the Department for Empowering of People with Disability (DEPD), and a member of the Social Welfare Department. The certificate, which NADRA officials said was issued by the social welfare department, is now issued by a new department DEPD, which was formed in 2018.

The process of issuing a certificate from DEPD starts with an application which is also available online or from the DEPD’s office. The form can be filled out and submitted at any center in Sindh, regardless of the district where the applicant is living, Ghulam Nabi Nizami, the director of DEPD Sindh told The Express Tribune. Along with the form, applicants are also required to provide their birth certificate, CNIC copies of their parents, pictures, and a medical record if there is one.

After finishing the form, the departments form a medical board of three members including a specialized government doctor. “If the doctor declares the disability less than 40 percent then the applicant does not qualify for the certificate,” Nizami said. He also explained that the reason for asking for the parents' CNIC is to verify their address to make sure they are from Sindh.

As soon as the doctor declares the applicant disabled, he or she signs the letter and sends it to DEPD, where the concerned officer hands it over or sends it by courier. The whole process takes 2-3 working days and makes it easier to verify certificates, Nizami said. “Sindh has started issuing QR code certificates which can be scanned by NADRA and don’t need to be sent back to DEPD,” he added. NADRA teams have also started accompanying doctors to one window camps in Sindh where they can have check-ups and issue certificates for disabled people on the spot.

Systematic struggles

Stories of NADRA officials making it difficult for people to obtain documentation are nothing new. Almost everyone has faced such obstacles and have had to continue returning to NADRA offices to request help. In many cases, the applicant either brings up or bribes the officer to get the documentation they need. Otherwise, they find a connection in NADRA who can get the document processed without extra fees.

Corruption is a common occurrence in Pakistan, and its prevalence in NADRA is no exception. “Every institution and sector in the country does have some bad fishes which keep the tanks dirty,” a NADRA official said. “But that doesn’t mean the whole system is flawed.” He said officers accused of corruption are often fired immediately because NADRA is very strict about this topic.

He said officers are often overwhelmed during rush hour, which is why they tell people to come back later. He also said some officers are not well-versed in the rules, which he considers unacceptable. To address these problems, NADRA hired 250 employees to work in their Mega centers, where employees have been trained for the past few months. After Eid they will begin their work on the ground.

NADRA also has a centralized complaint management system to help address issues with officers not responding or processing applications. They also cater to the complaints lodged through Prime Minister Performance Delivery Unit (PMDU). In this department, someone is required to respond within 48 hours and if they don’t the case escalates to the director, DG and chairmen, the NADRA official said.

In 2015, Amber Saba, a mother of three, used to visit NADRA centers every week to get her eldest son’s B-form made, which he needed to appear for the ninth board exams. After dozens of visits, she received the document two years later, in 2017. Saba said she had her CNIC as well as her husband’s and her mother in law’s. But officers continued to demand proof of property from before 1971, which she didn’t have. She said her father-in-law bought property in the early 80s and isn’t alive to help them with their application.

Even after a year of visiting different centers, she said officials still refused to tell her what the main issue was. Saba’s son didn’t appear in her papers for that year, and he had to repeat that year of schooling due to the holdup at NADRA. “The officer asked us to pay 25,000 rupees and we can get the B-form in two days, or else I will keep doing the struggle like I was doing since a year,” Saba said.

Since her younger son also needed to appear for the exam, she thought she would have to arrange the bribe so her children could continue their education. She had to take a loan from three relatives to pay the bribe, which was steep for someone who earns 20,000 PKR per month. “I cannot jeopardize the future of my children for that, so I arranged that,” she said.

One can find people like Saba in every corner of this country where just because they don’t know someone in an authoritative position can be misguided very easily and can also be talked into bribing the officials. “Back in 2016, it was difficult for me but today I am happy because both of my sons are going to universities and they are educated enough to understand the complexities which I and my husband were unable to understand, my sons are also earning by giving tuitions now so that sacrifice was worth for me but yes people like us who are uninformed about the rules or don’t know how to use the internet where the information is available are misguided very easily,” she added.

Saba said one of her cousin’s sisters was facing a similar issue with her B-form, which didn’t have one of her children’s details mentioned. To get it corrected, they had to go back and forth between offices. All that work was in vain until her brother-in-law’s boss, a retired colonel, made a call, which expedited the process immediately. “The document was made in no time,” Saba said, adding that everything in Pakistan is done easily for people have connections or money.

Noman Irshad, 31, who is still struggling to get his CNIC because he is a suspected Bengali national. He applied for a CNIC a few months after turning 18, bringing with him his parents’ CNICs. The request was processed but I never received a message to collect my card,” Irshad said.

After a few months, he went to inquire about his ID and was told there is an objection on his identity card, and the procedure to get it checked and corrected would be long and costly.

He became busy with school and work and put the issue to the side until two years later when his younger siblings went to get their CNICs made. Both of his brothers got their cards made without hurdles. He was shocked that everyone in his house could get an identity card except him. When he inquired why, he was told that his CNIC is flagged as a suspected Bengali and he needed documentation to get it released.

After getting a letter signed by the witness, he was told that the letter should only be signed by a BPS-20 or higher officer and after that, his CNIC could be canceled so that he could apply for a new one. He said after completing the requirements, he went to apply for a new CNIC but was told by the official there were additional requirements, which would mean he needed to go to another center. “The trail of going from this center to that center started, he said. “This continued for few years again.”

What are the rules of NADRA?

NADRA has specific rules when it comes to documentation, which they make very clear on their website in both English and Urdu. They also mention the documents needed to get a CNIC, including B-form. But when people have special circumstances, the guidelines are not always so clear.

“People don’t read the rules,” NADRA Public Information Officer Faik Ali Chachar told The Express Tribune. He said without the required documents, NADRA officers can’t process their request. Differently-abled people also need a certificate to be issued to them by the Social Welfare Department, which helps NADRA recognize and verify their case, he said. “People don’t bother to read rules at all and then complain that they are finding it difficult to get documents made,” Chachar said.

Rules are clearly stated on the NADRA website and the department has help desks where the applicant can information. Still, some people who’ve tried to go to NADRA to get CNICs made say officers do not convey details clearly, ask for bribes or hurry them away during rush hour. A senior official at NADRA, who spoke on the basis of anonymity, said out of 100 applicants, one 20 percent are first-time visitors, while most others are renewal or amendment cases. He said NADRA workers are obliged to help every visitor. “Any officer or representative at any NADRA office cannot and does not deny any service to any applicant.”

NADRA has step by step rules for each category of application. For example, for first time applicants who have just turned 18 and have their B-form ready, the process is easy because they already have a CNIC number allotted to them and can get their card made without hassle. People who don’t have B-form have to bring a parent to confirm that the applicant is their child. If parents are deceased, grandparents or other blood relatives are considered an acceptable alternative.

After relatives are received as witnesses by a grade-19 BPS officer, NADRA cross verifies the applicant. The applicant is also verified by a verification board along with his or her relatives, senior officials said. If someone is an independent case, like Sheeba, with no relatives to act as witness, NADRA requires witnesses from the locality where the applicant lives, or someone who has known the applicant for a long time. Even then, the zonal verification board must interview them and if they are not satisfied with the interview, the case may be given to the Intelligence Bureau (IB), which works to verify whether the applicant is from the area they are living or working in.

In such cases, witnesses have to give written consent that they take full responsibility for the applicant, after which the case will be processed. For a lost or stolen CNIC, no FIR is required, and the applicant only has to provide their CNIC number to get a new card issued, the official said.