There is not much wisdom in doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. Yet that is how successive governments in Pakistan have managed the economy. When faced by an economic crisis, our first reaction is to seek external loans under an IMF programme. This course of action also has a parallel requirement of economic reforms to avoid the crisis from happening again. Pakistan has never cared to do that.

Decision makers celebrate each agreement with youthful optimism, as if it is a win. Citizens, on the other hand watch with trepidation. They see the loan meter tick higher like a helpless passenger in the back seat of a lost taxi, knowing that in the end they must pick the tab. No decision maker is ever held to account.

So, we borrow with no plan about how to return the money. And the economy has sleep walked from one crisis to the next, hand-held by one IFI or another. We may now have come to a point from which there is no easy exit. There are also not too many countries and organizations willing to help. They know that this is a child that refuses to grow.

Today, external debt and the current account deficit are not just the country’s biggest economic issues, they are a national emergency. To learn how badly we have floundered, read this newspaper’s ‘Pakistan’s debt mounts to Rs53.5tr’ of 21 May 2022.

Solving the debt problem is critical for economic revival and security. If not done, there is every chance that the economy may default or face a Sri Lanka type situation. And a metaphorical Sri Lanka type collapse is not an abstract idea. It will be felt in every household and by every business. Some aspects of it may also flow up to the rarefied reserve of the over provided, whose privileges and surplus rent are paid for by everyone else. It is time to wake up. If the economic breakdown leads to social instability, it would hurt everyone.

Meanwhile, discussions with IMF have floundered. It has forced GoP to take the step it had said it would not take, which is to partly cut fuel subsidy. Yet, removal of fuel subsidy is not the only hurdle in reviving the IMF arrangement. GoP and IMF disagree also on several revenue and expenditure targets for the coming budget, as well as on the primary balance. IMF expects GoP to do away with power tariff subsidy, i.e., increase electricity tariff or cut DISCO revenue leakage. No government is willing to do the latter. IMF also wants a realistic estimate of provincial surpluses, a useful tool employed for years by governments to show lower than expected budget deficit.

Yet, the government has taken the hesitant first step to revive the arrangement with IMF. Macro stability is key to economic survival. The consequences of default are too grim to even imagine. We expect more such action in the coming days and the next budget, a taste of which was also felt yesterday in the steep cut in HEC’s budget. It is a delicate tightrope that GoP must walk as it weighs the political cost to it vis a vis the risks to the economy. No one wants a default on their watch. The markets have responded as the Rupee and the KSE index gained value.

The economy favours special interests. Such privileges hurt, but they are not the only reason for the economy’s distress. Flawed policies and lack of strategic thinking is to be the greater issue.

Contrary to how decision makers sound in news headlines, it is clear that the economic crisis does not arise merely from a lack of access to foreign assistance. While IMF is needed, it is an insufficient response and one that ensures that before long we will have the same problem again. Even a casual analysis convinces us that government must revisit its entire economic policy agenda. A plan to avoid future current account crises should lie at the centre of any substantial engagement with the IFIs and other bilateral partners. Before we do so, we must also begin to set our own house in order and make some difficult and delicate political choices.

Why is an IMF agreement insufficient response? IMF’s mission is not growth and development. It helps with temporary balance of payment emergency. IMF looks at debt sustainability from a cash flow point of view. So, if Pakistan will receive enough loans to enable it to meet this and coming years’ external payment obligations, including interest and amortization, IMF considers the situation sustainable. This is a short-term perspective emanating from the IMF’s mission to help member countries meet emergency BoP challenges. But piling debt on debt worsens the malady. As our over 20 visits to IMF testifies, Pakistan’s case is more enduring in nature and entirely of its own making. It stabilizes the economy while under the programme but goes back to old ways very soon. At each visit, Pakistan is in worse shape than it was the last time.

The depth of reforms that our economy needs can only be set right by strong and committed political leadership engaged with the people of Pakistan and working for growth and development. We have not made the necessary reforms and thus the economy has not stabilised.

Underinvested economy

So, let us look a bit deeper into what has caused the economy to stay in this precarious state with frequent crises and repeated IMF visits. Governments have not shared much official analysis or strategic plans to inform about what ails the economy. Also, there is a lack of policy action. For over two decades, share in GDP of the productive sector, agriculture and manufactured goods, has fallen steadily. Yet there is no discussion about it or any plan to correct it.

In the last 30 years, both public and private investment has declined in Pakistan. But nothing has been done to correct it. Investment in manufacturing is shockingly low at 1.5 per cent of GDP. As a result, export as a percent of GDP has declined. That figure stood at 19 per cent of GDP in 1990. It is now 8.5 per cent. In some respects, the current account crisis is the other side of the coin of underinvestment.

All business activity, especially manufacturing, need infrastructure, quality people and solid legal and governance support. Governments must supply power and other utilities as well as predictable and stress-free enforcement of laws. Most rapidly growing economies set aside considerable sums of public money to this end. This doesn’t happen in Pakistan.

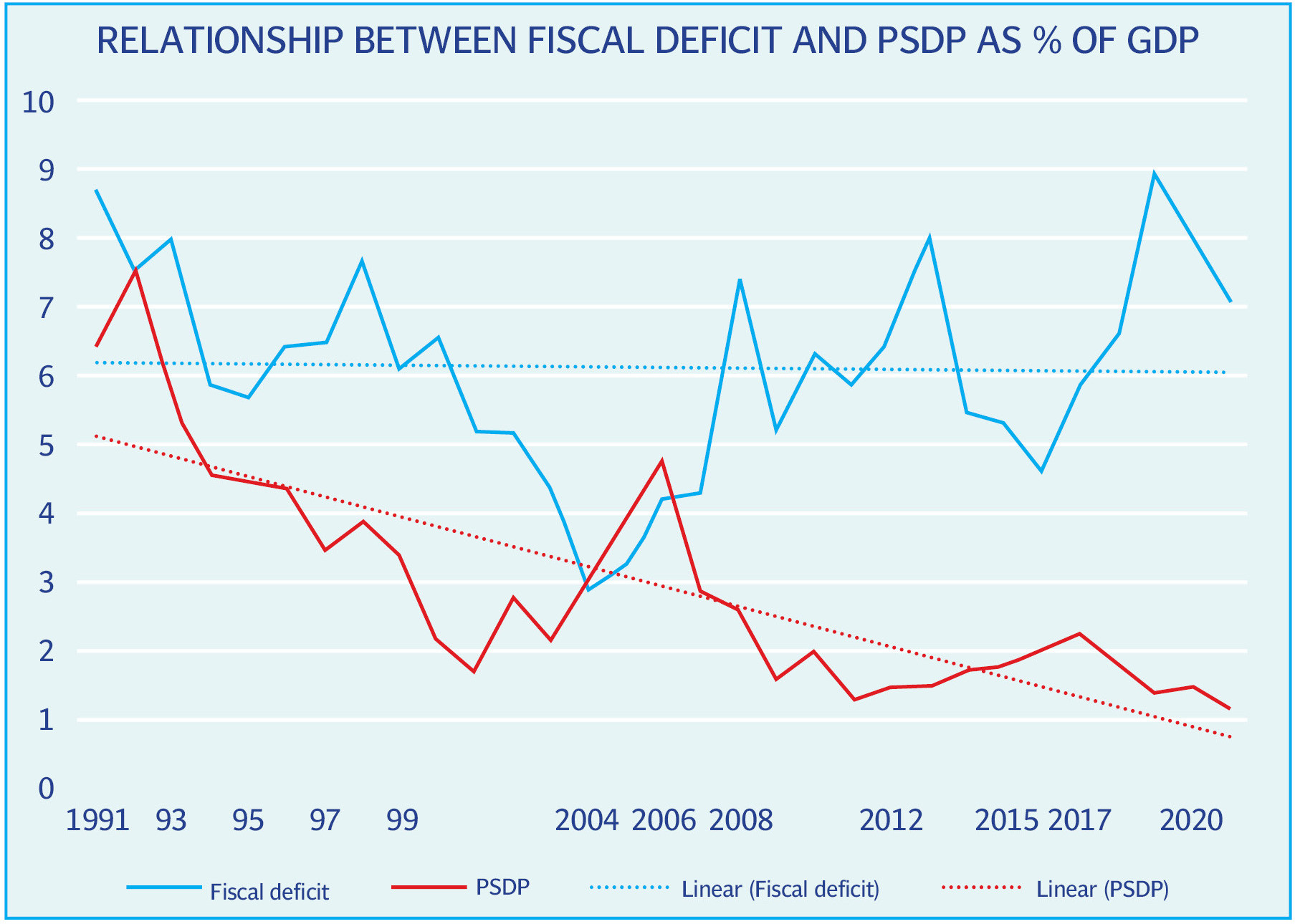

Government builds infrastructure and human resource through allocations in the PSDP. But PSDP has been in terminal decline. It was never enough to meet our needs. Today it exists in name only.

The economy is under investing in key growth inducing infrastructure support. Expenditure as per cent of GDP on health and education has been flat despite alarmingly low indicators in both. While public investment declined, fiscal deficit has stayed at high levels throughout the 30 years. Our flawed political choice is evident from the trendlines added to the chart below. Budget deficit has stayed at about 6 per cent of GDP, while PSDP has fallen rapidly.

The economy is under investing in key growth inducing infrastructure support. Expenditure as per cent of GDP on health and education has been flat despite alarmingly low indicators in both. While public investment declined, fiscal deficit has stayed at high levels throughout the 30 years. Our flawed political choice is evident from the trendlines added to the chart below. Budget deficit has stayed at about 6 per cent of GDP, while PSDP has fallen rapidly.

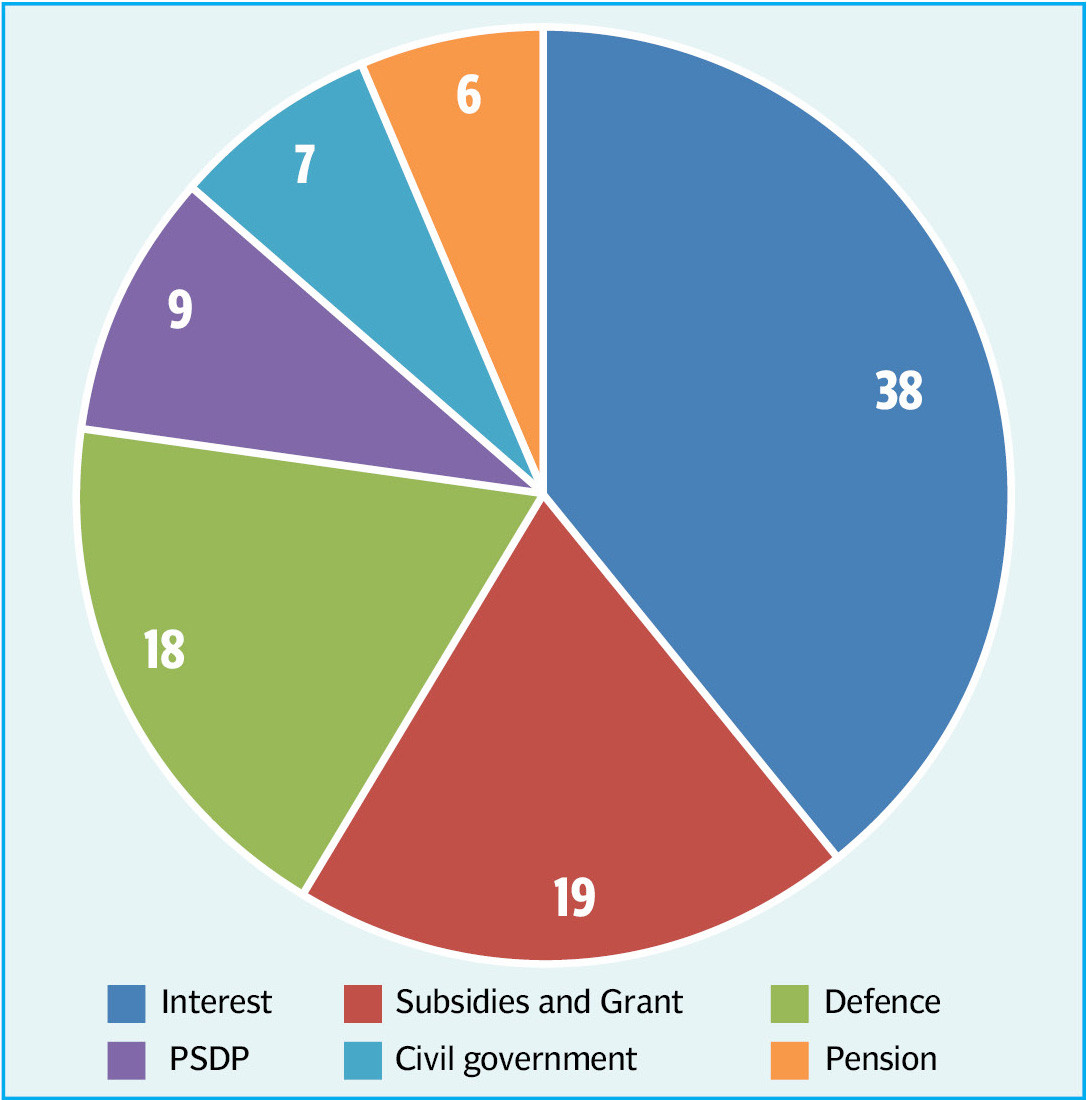

If public investment is down and budget deficit is high, where is government money going? To subsidies led by IPPs and inefficient PSEs. But mostly to paying of interest to domestic and foreign creditors. When the government says that it will increase tax to GDP ratio, 78 per cent of that increase will pay interest and a fair part will pay for subsidies and grants. Just these two items are more than 100 per cent. So, after paying the creditors, government borrows to meet all other expenditures. (Not all subsidy and grants are inefficient spending. Some grants help the vulnerable population. Others help in supporting economic activity. BISP is not included here).

Largely, government does not spend the money judiciously and nowhere enough that would help build a solid manufacturing base in the country to boost exports.

Let’s take a minute to dwell on the logic of public finance in Pakistan. We use 78 per cent of net federal revenue (equal to 38 per cent of total federal expenditure) for interest payment, and then government borrows more money to pay for its other expenditure, which further adds to subsequent interest payments. And as IMF now stipulates that the primary deficit must stay positive, so each year, government spends more and more funds to meet interest expenditure, while restricting most other expenses. Citizens and businesses suffer for want of public goods and from the ever-increasing demand for levies and taxes.

As government borrows more to pay back interest and for its other needs, it deprives the private sector from much needed finance. That partly explains the falling investment. So, there is a connection between the four indicators of falling PSDP, reduced private credit, fall in investment to GDP which together lead to fall in exports. But government hasn’t accepted this link. Their main focus is more loans.

Let’s take a minute to dwell on the logic of public finance in Pakistan. We use 78 per cent of net federal revenue (equal to 38 per cent of total federal expenditure) for interest payment, and then government borrows more money to pay for its other expenditure, which further adds to subsequent interest payments. And as IMF now stipulates that the primary deficit must stay positive, so each year, government spends more and more funds to meet interest expenditure, while restricting most other expenses. Citizens and businesses suffer for want of public goods and from the ever-increasing demand for levies and taxes.

As government borrows more to pay back interest and for its other needs, it deprives the private sector from much needed finance. That partly explains the falling investment. So, there is a connection between the four indicators of falling PSDP, reduced private credit, fall in investment to GDP which together lead to fall in exports. But government hasn’t accepted this link. Their main focus is more loans.

Consequently, debt and debt servicing are now out of hand. Let’s briefly look at the numbers. Total foreign debt was less than $ 60 billion in 2015. In six years, it has more than doubled to over $ 130 B in December 2021, and the borrowing continues. Returns on the labour of Pakistanis is being handed over to outsiders.

On the other hand, in FY 2015, exports of goods and services was $ 30.4 billion. It barely increased to $ 31.5 billion in FY 21. So, while foreign debt grew by over 200 per cent in six years, exports grew by a small 3 per cent. During the same period, debt servicing grew by about 250 per cent. So, how would more loans help? They only worsen the situation.

Continuous dependence on debt has forced us to borrow from expensive sources as concessional sources dry up. Thus, we see that between 2010 and 2021 share of low cost mostly long-term Paris Club debt have gone down from 25 per cent to 8.8 per cent. Share of multilateral debt, another source of concessional loans, fell from 42.7 per cent to 27.6 per cent. As against this, the share of high-cost bonds/sukuks went up from 2.7 per cent to 6.4 per cent. Cost of the three bonds floated in FY 21 ranged between 6 per cent and 8.9 per cent. Share of commercial loans are up from zero in 2010 to 8.4 per cent of total debt in 2021. Their cost is in the range of 5 per cent.

It is not surprising then that our ability to repay has worsened as seen from the debt sustainability indicators. If external debt servicing uses up more than half of exports and about a quarter of exports and remittances, how will Pakistan import the machinery needed to produce more, in addition to importing essential energy and food.

Each visit to the IMF or a new loan signed is portrayed as a victory, without thought to its cost. Each year, servicing of external debt has handed out more and more funds from the country to overseas creditors.

Since FY 2001, Pakistan has paid an average of US $ 1.4 B annually in interest alone. Average interest paid in the last four years is US$ 2.7B annually for a total of US $ 10.7 B since FY 18. Since FY 2001, Pakistan has paid external creditors more than it has received from them. In 20 years, it has received $ 112.6 B and it has paid back $ 118 B in interest and principal. Yet its external debt has grown by 228 per cent from $ 37.2 B in FY 01 to $ 122.2 B in FY 21. We may have paid back the original loan more than once and still owe it to the creditor. This is because often the purpose of new loans is to repay past loans with the result that over 70 per cent of new debt is to meet balance of payments needs. Returns on the labour of Pakistanis is being handed over to outsiders.

‘Que sera, sera’ approach to policy

External debt must finance projects that create GDP growth and exports to enable the economy to repay. If over 70 per cent of new debt is consumed, the economy does not create the means to repay. About 4 per cent of our GDP has flown out annually in debt servicing in recent years.

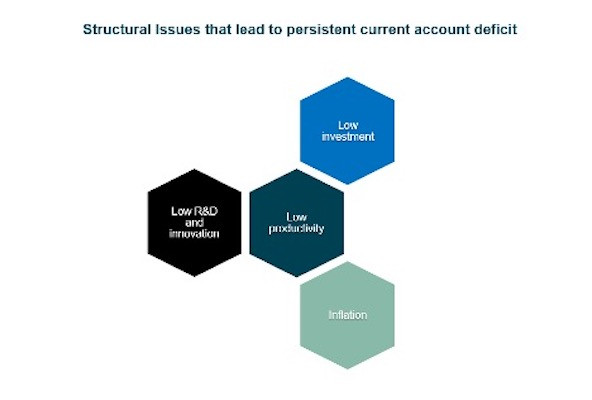

As a result, the economy is caught in a trap of low investment, low productivity, low exports, and high debt and debt servicing. It is not clear if there is a plan to correct it. Whatever the reason, it shows the inability of successive governments to reform. While government should do everything to help the economy produce more and industrialize, it stays focused on the short-term.

What should Pakistan do? Get serious

What should Pakistan do? We must change our present ‘que sera,sera’ approach to decision making. There are consequences for the decisions government takes for which the whole country pays a price. Enough is enough, we must get serious and everyone must play their part:

- We need political stability, without which governments cannot meaningfully begin a reform programme.

- Each year, government must set targets for fiscal and current account deficits and cut its coat accordingly. Parliament must approve and monitor. This is happening via the annual plan even now. But no one pays heed. Now the government must be held to account by parliament.

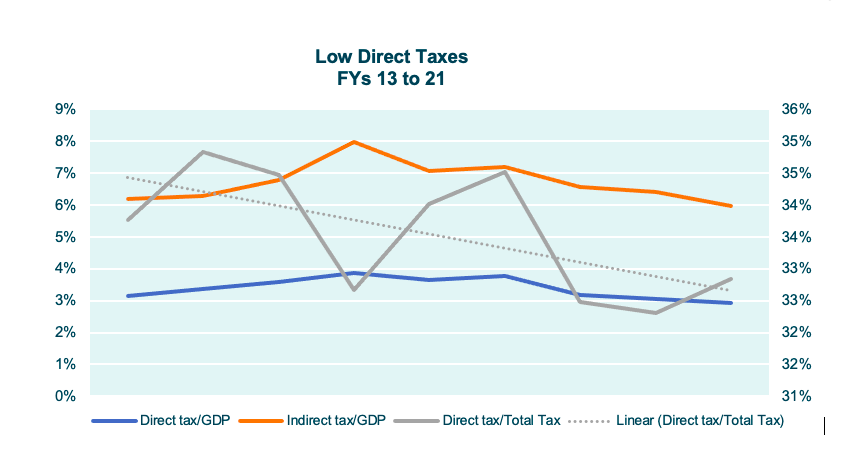

- To manage the budget deficit, do not just rely on indirect taxes. GoP has limited the discussion about increasing revenue to raising indirect taxes such as higher petroleum levy, GST and import tariff. It serves special interests. Yet, despite lip service in every budget speech to increase direct taxes, and we may hear it again this year, its ratio is no better and has in fact gone down lately. Contribution of indirect taxes is about twice as much as direct taxes. Large tax exemptions, favourable rates, and tax evasion prevent increase in the share of direct taxes. The common person is expected to keep funding the large budget deficit.

- Pakistan may have to seek debt relief from all lenders in the shape of reduction in interest rate or reduction in principal amount. We have sought rescheduling of debt before. Also, IMF would need to be persuaded as it recommends debt relief when debt is unsustainable. So far, it considers our debt sustainable. To convince the lenders, we must go with a sound plan for economic growth and correction of elite privilege. Pakistan has cause to make the appeal.

- Increase exports: as production of exportable goods has not grown, it is hard to increase exports quickly. Government may make an item wise study of what export could increase quickly, possibly with incentives. Even a billion dollars in extra export will help.

- Imports: Do away with all non-essential goods imports. Also, make an item wise review to find domestic substitutes for imports or bring some items quickly into production with incentives. Government may consider rationing subsidized consumption of oil.

- Earmark remittances for repayment of external debt by limiting imports, rather than just borrow to repay. Of course, money is fungible, but earmarking sets a target in the government’s mind to direct a certain amount towards debt repayment. Ten percent would mean a reduction in debt by $ 3 billion.

- Prevent re-entry of Afghan transit imports to help rebuild our industry.

- In addition to a Saudi facility for deferred payment for oil, we may request the same of Qatar.

- Restrict portfolio investment and end the volatility and transfer of resources that it causes.

- Gradually, we must start accessing external debt to only finance projects that create GDP growth and exports. It is not possible to pay back debt that is consumed and not invested.

Some deeper reforms are needed with a medium-term timeframe:

- Restructure domestic debt. There are IMF guidelines on the subject. Government may make a serious effort to use the funds spared from debt servicing for development.

- Make power sector financially sustainable to reduce burden on consumer and tax payers and to remove payment uncertainty to producers. Doing so could reduce the budget deficit. The original IPP investors have mostly left. It is clear also that the consumer or the government cannot meet the cost of power along with the generous concessions that IPPs avail. Also, because of long delays by the government in paying tariff differential subsidy, a part of IPP profits stay on the books for years without getting realized. Today everyone suffers, producers, buyers, and government. Industrial production and exports have especially taken a hit. The previous government carried out a study to assess how the sector can be made sustainable. Government may build on that study and begin exchange of ideas with IPPs and experts on how to make the power sector sustainable,

- Recast the PSDP and reorient project selection metrics so that they support exports by raising private sector productivity

- Within SBP’s monetary supply limits keep liquidity flowing, through specific measures. SBP may ease regulatory requirements for enhanced credit. It may revive TERF or a like facility. Also, government must bring to fruition its old plan of setting up an EXIM bank. They could use Export Development Fund for the purpose, if needed. Government must also revive DFIs: Private sector needs fixed rate long-term financing for industrial growth. Our fall in investment has closely followed less credit by doing away with DFIs.

- SEZs is another government plan that has long been talked of but not put into operation. Government must operationalize SEZs.

- Increase productive capacity and self-reliance. Increase domestic sources of energy. Since 2012, government’s focus has been on import of LNG. There is need for a revised petroleum policy and especially a policy to begin shale gas exploration. The new policy may assist exploration companies access finance and technology and mitigate their risk.

- All international agreements of an economic nature must be open to parliamentary review. If confidentiality is important, they may be classified and limited to review by the relevant parliamentary committee. Secrecy hasn’t worked. Examples are our high indebtedness and international contracts that lead to arbitration awards against us. When something goes wrong, as it frequently does, tax payers and consumers pay. Decision makers are never held to account.

The present crisis is an opportunity for policy makers to learn from past mistakes and to make bold reforms. To be a respected member of the global community, we must reduce dependence on others. Government must take tough decisions even when they infringe on powerful interests. Top leadership must start a national dialogue on a widescale and emphasise that everyone must contribute.

The author is a former commerce minister and the CEO and Chair of the Board of the Institute for Policy Reforms. This feature is based on the Institute’s recent report “What to do about Pakistan’s mountain of debt?’. All graphs and data are also from the report.