Bindiya Rana always felt different. She knew she wasn’t like the other boys her age. In fact, what exacerbated her aloofness was the way she was treated by those around her.

One thing that always struck Bindiya was how she was sent to a public school, while all her siblings went to private institutions. At the time, her young and eager mind couldn’t comprehend the discrimination. As she looks back today, she realises it was on account of her being the ‘third gender’.

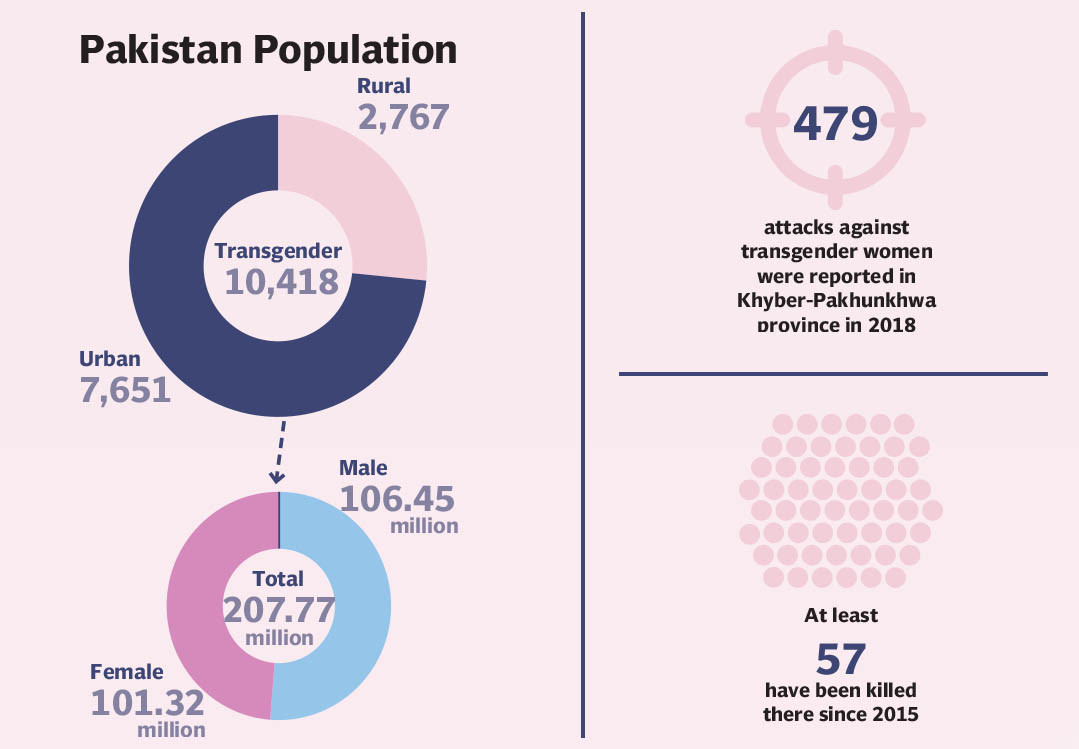

Discrimination is the one word that has become thematic in the lives of members of Pakistan’s transgender community. According to the 2017 census, of the 207 million people living in Pakistan, hardly 10,418 identify themselves as transgender. This in itself is a sham, argues Bindiya, claiming that the number is far higher.

Rejecting the 2017 census, Bindiya believes the population of trans people in the country is far higher than the 10,000 that has been reported.

“There are more than 100,000 trans people in Pakistan who are HIV positive according to medical records. Then how come there are only 10,000 trans people in Pakistan?” questioned Bindiya.

She added that the census was a ‘sham’ and that government bodies were doing what they do best, which is ‘lying’.

Bindiya, born male, says she started feeling more feminine at a very early age. “I used to wear a dupatta (shawl) when my brothers and father went out from the house,” she said, “I liked cooking in the kitchen and took interest in makeup.”

The 50-year-old trans rights activist recalls her formative years when her father admitted her to a public school, unlike her other siblings who all went to private one.

“I didn't understand why my brothers and sister went to an English medium school and I went to one where we used to sit under a tree,” she said, “The weather was very harsh and there was no cold water to drink.”

At home, Bindiya was often rebuked by her brother for being too feminine. “They scolded me for behaving like a girl. They did not like the way I walked and talked. Harassment for me began at home,” said Bindiya. “But my parents also supported me, to some extent.”

Feeling uncomfortable at home, Bindiya joined the Guru-Chaila community in her teens. “When I joined my guru, she was very caring and supporting,” Bindiya reminisces. “Her chailas were also very welcoming. I felt safe and at ease.”

Believing she had support from her family, Bindiya was once called by her father to visit home as who she ‘really is.’

“I was really proud that my family was accepting me for who I am,” said Bindiya. “But my guru warned me not to go dressed up as a woman. I did not listen.”

On reaching home, Bindiya was shocked to see all her close relatives there. Her father asked her to sing and dance like she did in events. Her father had a stack of Rs 100 notes and asked her to dance like she did at events.

Ashamed, she told him that she can't. “I sat down on the carpet and started crying. My mother also intervened and asked my father to stop creating a scene,” she said.

Sharing an incident of her close friend's death, Bindiya said they were asked strange questions when they reached a police station to get clearance for her friend's body to take it to her native village.

“Do you people bury your dead at night, at home or vertically? Are there any funeral prayers? We were asked questions as if we were not humans,” she said. “They were all smiling at us and making fun of us while asking us these questions.”

Transgender rights

The transgender community was criminalised by a people dominion by the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, and trans people still suffer as a result of the attitudes it engendered.

At different times in history, societies around the world have had numerous approaches concerning gender diversity. The community, ordinarily referred to as the ‘hijra’, maybe a taboo that features trans, intersex, and castrated persons. For a minimum of 2000 years, these individuals have existed in South Asia.

The British Empire, on the opposite hand, brought with it a restricted construct of gender that was exploited as a part of a bigger divide-and-rule approach. According to the Asian Studies Journal, British colonialists sought to construct a brand-new natural cohesion during which they tried to enforce a rigid perception of ‘masculine’ men.

The apparent masculinity of men was sought to classify ethnic and non-secular groupings in South Asia, starting from the alleged "martial races" of Sikhs, Pathans, and Muslims to ‘effeminate’ Bengalis. "They sought-after to manipulate and erase this cluster from culture through the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871," says Jessica Hinchy in the journal. "When the colonisers found a gender-variant community of Hijras United Nations agency broken this elaborate hierarchy."

After Pakistan gained independence, the Act was formally repealed. However, purposeful progress wasn't accomplished till 2009, once the country's supreme court determined that provincial governments should defend the rights of the community.

In 2017, the National Assembly approved the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) bill. This was later amended and passed unanimously by the Senate in March 2018.

Subsequently in May 2018, the National Assembly approved the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018. The act not only empowers transgender people to determine their own gender but also safeguards their basic human rights of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness.

The Act not only emulates the tenets set out in India’s Transgender Persons Act, but is in fact full copied from it. In fact, the minister who presented the Act in the assembly didn’t even bother changing its heading.

The act states that person would be sentenced to six months in prison and served a fine of Rs50,000 if found guilty of forcing a trans-person for panhandling purposes. It also prohibits discrimination by educational institutions, employers, health services, traders or whilst using a public transport.

However, many still feel a lot more needs to be done for transgender inclusion within the community. “The Act has some gaps obviously and there is room for amendments because there are several issues that we still face that aren’t addressed in it. For example, the act has no clarification over the issue of marriage, family, adoption, or how gulf countries will operate when we have to travel for Hajj or Umrah,” said Maya Zamaan, as activist who has been protesting for transgender rights for a long time.

“I am given an identity but what are my rights if I want to get married? Which gender can I marry or can’t I marry? And what are the rules if I want to adopt a child,” she added.

When the Act was being drafted activists fought for the identity of trans persons to be self-determined rather than decided by a medical examiner, gurus or counselors – this went a long way in lending some basic fundamental rights to the community.

Similarly, according to Maya, the same way other minority and marginalised groups are, transgender people should also be given a quota. “We have come a long way but the road ahead is still long. Our presence in offices will help in acceptance among people because it doesn’t matter if we have a separate gender on CNIC, if practiciality the practicality on the ground level doesn’t align with that,” the activist added.

The said Act had come into existence through the tireless efforts of the Gender Interactive Alliance, a non-governmental organisation that has come a long way since its inception in 2009. Bindiya, as the GIA’s president, commands some respect in private hospitals and they now tend to accommodate a transgender person needing medical aid.

“They know who I am, so they help us even in the middle of the night, but if a transgender person goes by themselves, hospitals do not treat them,” said Bindiya.

There have been instances when transgender people have been denied medical treatment simply on account of their gender. One such incident occurred in Peshawar in 2016 when Alisha, a transgender person, was shot eight times. She would later succumb to her wounds at Lady Reading Hospital because the staff couldn’t decide whether to put the 23-year-old in a male or a female ward.

Bindiya lamented that hospitals don’t have a third-gender drug distributing window. “You see one window for male and one for female. Where is our window? Aren’t we human beings?”

Even entering hospitals is not a walk in the park for a transgender person. Bindiya says they are subjected to taunts and humiliation by guards at the entrance. “Guards ask us, ‘why you are here?’ ‘Where are you going?’ We go to hospitals in pain and agony and they treat us like this,” she said.

Even after getting through the embarrassment at the entrance, Bindiya says doctors are no less demeaning.

“The male doctor says female will check; the female says male will check,” said Bindiya. “And for hospital wards, there is only male or female. There is no ward for us. Where will we go?”

According to Bindiya, discriminatory remarks are made by the doctors during medical check-ups. She further claimed that the trans people mostly self-medicate to avoid all the humiliation.

“If a normal person has an allergy, then it is just an allergy, if a trans-person has an allergy then it will be because of sex-work,” she lamented. “Hospitals do not take us seriously. They make fun of us so we try not going there unless there is a severe disease and consultation is necessary. Otherwise, we just go to the local pharmacy and get medication from there.”

She decried the stereotypical mindset of Pakistani society that was quick to paint her whole community with the same brush. “Because of some sex-workers [in our community], people believe that we all are sex-workers. We would not beg in the streets if we were in that line of work,” said Bindiya.

According to UNAIDS Pakistan Reports 2017, one of the issues that has opened up public discussion about LGBT rights has been the effort to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS among men who have sex with other men, but who do not necessarily identify as being gay or bisexual. The report suggests that they are targeting night truck drivers who are known for having sex with younger men.

A 2009 survey report titled ‘Multiple Risk Among Male and Transgender in Pakistan’, published in the Journal of Health Research found that male and transgender sex workers in Pakistan were at high risk of HIV/AIDS. Due to lack of awareness on this topic, the sex worker's health is at risk and needs to be focused and paid attention on and victims should be treated.

Violence

According to a Human Rights Watch report published in 2017, law enforcement agencies were ordered by Supreme Court of Pakistan in 2009 to improve the response in cases involving transgender people. Despite these orders, reports of violence against the transgender community have only increased over time.

Alisha’s was one of many cases in recent years. In April 2020, Musa, a teenage Christian trans-boy was raped and killed in Faisalabad. In July same year, Kangana a, trans-woman was killed in Rawalpindi by unknown assailants whereas in September Gul Panra, a trans rights activists, was shot six times in Peshawar. She was rushed to a local hospital but succumbed to her injuries. In April 2021, Mumtaz, a 60-year-old trans-person was killed in Karachi’s Korangi area when unknown assailants broke into her house and shot her.

Because of the power-dynamics, transgender people have been kidnapped, raped and even brutally killed. When they seek aid from law enforcement agencies, treatment at police stations is not different from hospitals even though the Transgender Protection Act states that the law enforcement agencies will be sensitised to transgender rights.

“They make fun of us saying that the nature of your work is the cause of the violence against you,” said Bindiya. “You are what you are so we cannot do anything.” With the police’s callous attitude, Bindiya questioned, “How are we supposed to tell the police where and how we have been beaten?”

There is hardly ever respectable employment for members of the marginalised community. Bindiya, asserts that law enforcement agencies are troublesome for the transgender community who are barely making ends meet. “Police sometimes picks up transgender beggars and hand them over to Edhi centres,” said Bindiya. “If they don’t beg, how will they eat? If they do not beg then they are forced to do the only thing the society wants us to do. Believe me, no one wants to do it on their own will.”

The transgender protection act incorporates all necessary arrangements to make the transgender people’s lives easier. “We had demanded a quota of jobs. We should have reserved seats for government jobs,” asserted Bindiya. “But the government has reduced it to what is acceptable to them.”

“They declared us 10,000 only because of the job quota of only 3%,” Bindiya claimed. “More transgender people will get jobs if they tell our original number, which is in hundreds of thousands.”

To make matter worse, Bindiya claims police generate a fake FIR (First Information Report) and make transgender people do unnecessary medical check-ups.

“We will bring the victim to the hospital, complete all the formalities. Only then will the police register the FIR,” she said. “By then, the culprit runs away.”

She said that we need to sensitise our society because the one we live in right now, cares more about what others may think about them instead of the sentiments of our loved ones.

“I only wish that people won’t marginalise us so much that we start questioning our existence,” Bindiya said as her voice broke. “We only want people to acknowledge that we are humans as well and have the right to live in this world as much as they do because this world is ours too.”

Author tweets as @jt76007

Additional reporting by Yusra Salim