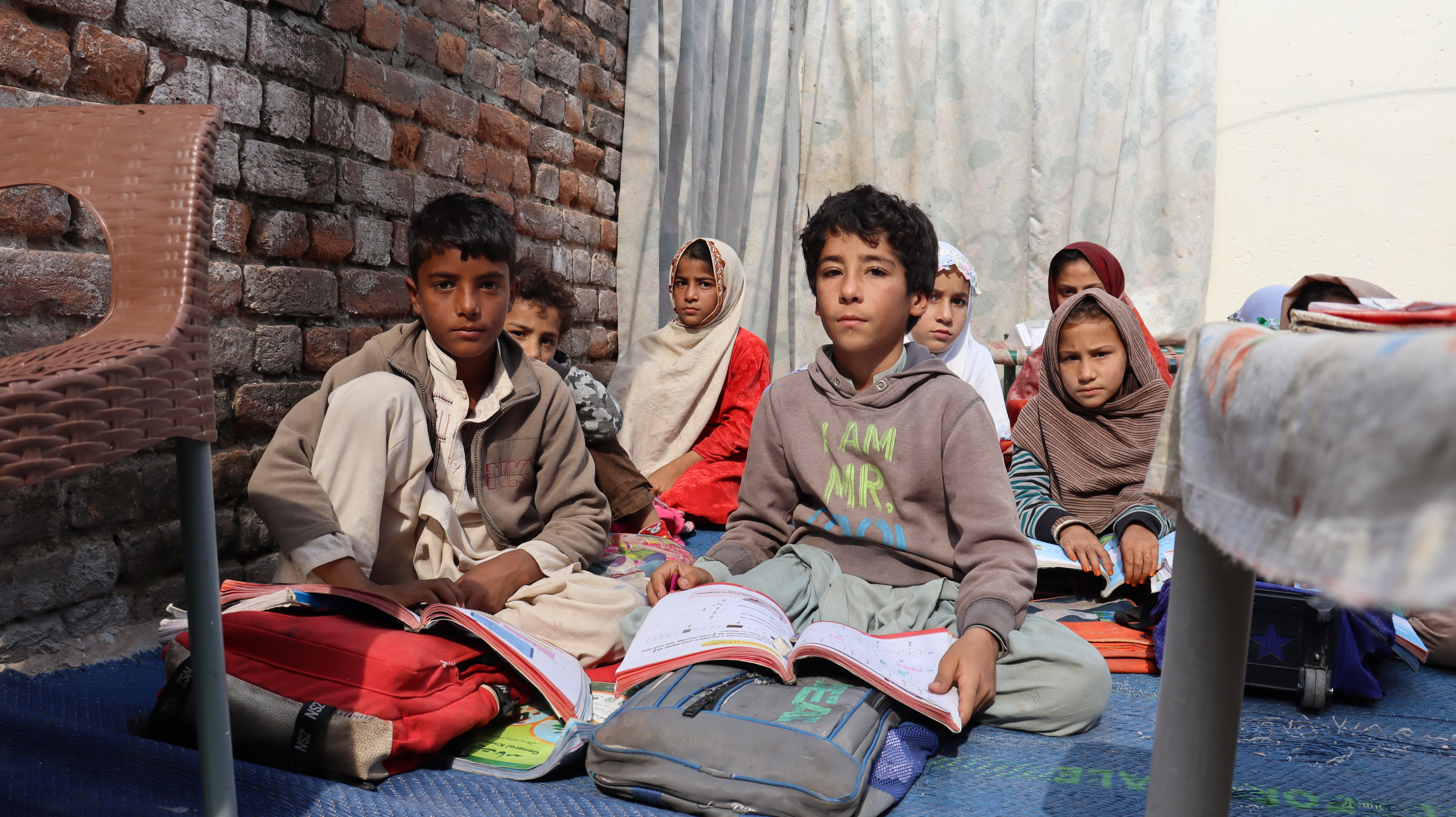

In the shadow of a wall, 11-year-old Sana sits on the floor to memorise the day’s lesson. Currently preparing for a class five exam, she first came to this multi-grade, one-room community school in class two after leaving a private school. “My father enrolled me in this school because he was unable to pay the monthly fees of the private school. He is a daily wager,” she says.

Next to her sits 10-year-old Zara Bibi with books of grade three in her hands. She had left her education after a school run by a non-governmental organisation was closed. “I was over the maximum age for a government school, which too was quite far from my home and the private school nearby was expensive for us,” she says.

In another ramshackle informal school, children from prep to class five study in darkness as the daylight struggles to enter the congested room that has no windows. In the room, 14-year-old Hameed Khan is reading class four books. He was refused admission in a formal school because he was over the maximum age.

The roof of this room was installed with donations from a non-governmental organisation as the government gives no funds to build or repair the structure.

Studying in different informal primary schools in the suburbs of Islamabad are the children of daily-wagers, janitors, ragmen and Afghan refugees. Many are rag-pickers who study in the morning and work in the evenings to make ends meet.

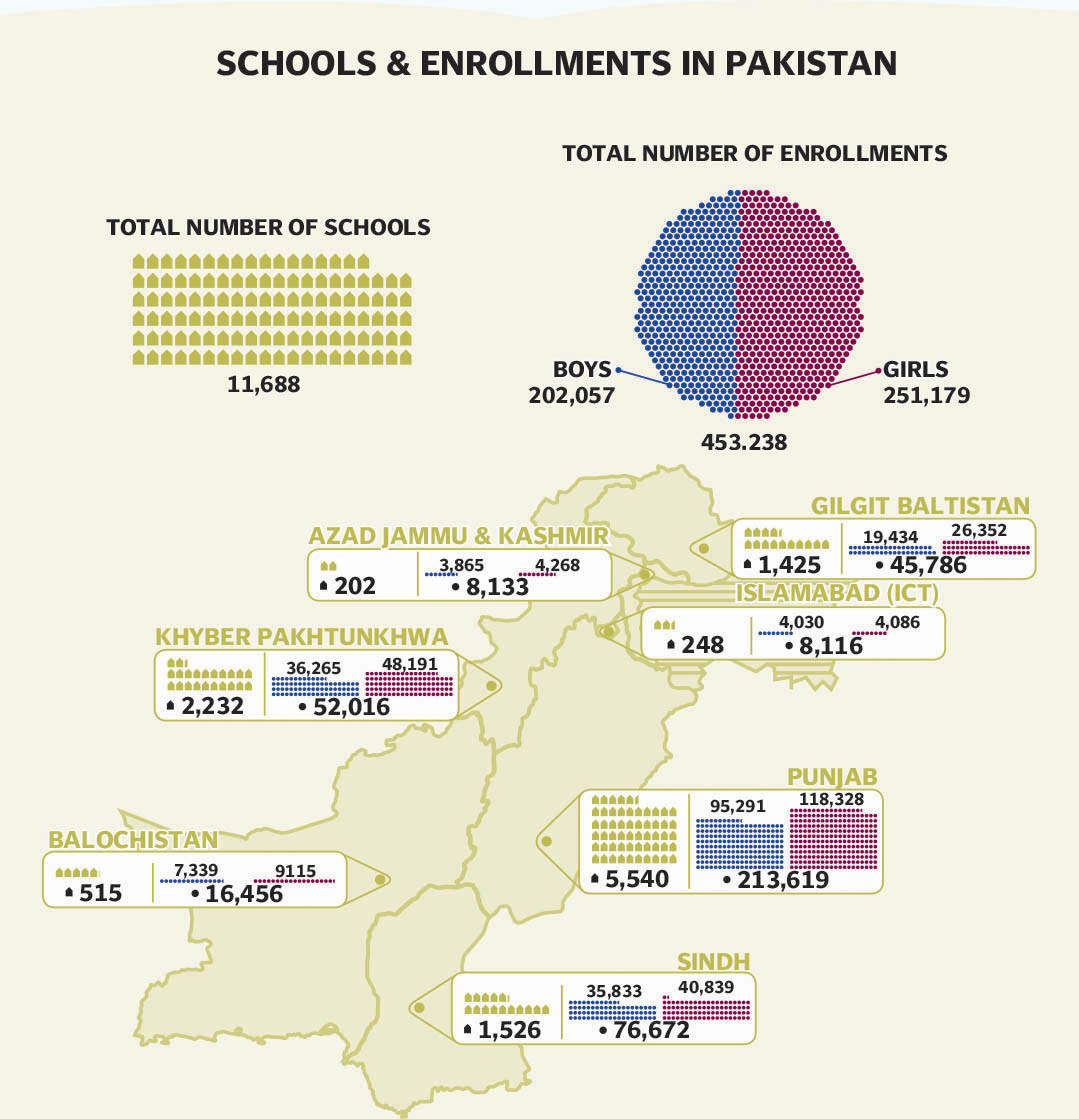

Some 10,000 students were enrolled in about 248 community schools in Islamabad Capital Territory before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, of them about 2,000 students did not return when the schools reopened.

The students have been given textbooks and learning material after four years that still are not complete. Some teachers complain that they haven’t received mathematics and science books. Deficiency of funds and delays in their releases are one of the main challenges faced by these schools. Teachers’ salaries of over four months have been pending. Lack of facilities and incentives have led to the dropout of hundreds of children.

“Demotivated teachers teach uninterested poor children who often dropout in the middle or don’t enroll in formal schools for further education” explains an official. “If given facilities and scholarship opportunities, they can excel like other children of formal schools”.

In 1995, under a project of the then Ministry of Education, some 12,304 non-formal Basic Education Community Schools (BECS) were established for out of school children across the country. The BECS Schools have a single teacher and single classrooms from grades one to five, and the premises is provided free of cost by the community. Single teacher is responsible for all the classes of the school by adopting multi-grade teaching methods; based on formal school curriculum. At the end of grade five, formal sector conducts the examination and allows admission in grade six in formal schools.

The community schools programme was started to supplement the formal education, and achieve universal primary education by extending free, flexible and modern basic education opportunities to out-of-school children and youth, having no access to the formal system of education, especially disadvantaged children, girls and special children.

According to a government’s 2018 documents, more than 5 million out of school children have graduated from these primary schools and enrolled into formal schools. In the same year, the pass percentage was 89.5 of class five.

The federal government was running these schools until last year when the Council of Common Interests decided to hand them over to the respective provincial governments. Now except for the federally administered areas, the schools have been handed over to provinces in June this year.

Since the last PC-I of the programme expired on June 30 the fate of over 1,800 schools of ICT, Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan managed by the federal government hangs in the balance. Like the federally administered schools, the status of schools in Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan is also uncertain since their governments have not yet formally decided anything about them. Only Sindh government has merged the informal setup with the formal schools this year and increased their salaries as per the minimum wage. However, the salaries of all the teachers working for these informal schools across Pakistan have been pending since July.

Promises unfulfilled

An elderly teacher who started working at one of these informal schools in 2002 says she used to paid Rs 1,000 per month initially. Now she gets Rs 8,000 per month, less than a labourer. “Even a housemaid earns more than this. This is the kind of respect teachers receive in this society,” she said.

“The year 2022 is around the corner and it’s going to be 20 years that I have been protesting and staging sit-ins for our rights. I was nominated in the FIR, faced inquiries and was manhandled by the police. Now I’m exhausted and sick. My fragile health does not allow me to take part in such activities,” she added.

She said teachers have to bear all the school expenses on their own as the government gives only Rs 1,000 to pay utility bills. “We are asked to manage expenses by collecting fund from the community elders. But there are hardly any well-off families in the vicinity, besides nobody want to donate,” she said.

The teachers are directed to fill the forms time and again to get donations from non-governmental organisations, but hardly anything reaches the schools and the poor children. “Different governments came and went but nobody did anything for these schools. In 2011, Imran khan came to our protest and announced that he will regularise us but our status is still uncertain and we are without salaries again,” she said.

‘Step-motherly treatment’

“Like the formal school, community school teachers give 100 per cent result of class five but in return they have always received step-motherly treatment,” said Mohammad Nawaz, a teacher who runs a school in Chatha Bakhtawar, ICT.

“In each school there are at least 30 to 50 students whom teachers teach five hours a day like the formal teachers but the minister alleges the teachers only teach two hours a day so they are not entitled to better pay packages. But at least there’s no ghost school in ICT,” he said adding that inspections are conducted and now there is a monitoring system in place but they don’t want to allocate funds on one pretext or the other.

“The teachers are unable to bear household and schools expenses in this paltry honorarium,” he said. “Who can meet household expenses in this honorarium when the price of every commodity has touched the sky? Even a bag of flour is costing over Rs 1,400 rupees”. He demanded that their salary should be raised in accordance with the pay packages of formal primary teachers.

The teachers have held protests and lodged complaints on the Prime Minister Citizens’ portal but their wailings have not shaken the power corridors. Now they are being threatened that their schools will be closed if they protests. Last time when the teachers protested, school of a female teacher, who was leading the agitation, was closed by the officials, they say. They only got it reopened after assurance that they will not take part in political activities.

Rights on the line

Saad Gilani, Senior Programme Officer at International Labour Organisation maintained that paying teachers even below the minimum wage is a violation of national as well as international labour laws, and the teachers can approach the court for relief. “It’s not limited to the informal sector only. In the formal, private sector too, teachers are paid below the minimum wage,” he added

“As the teachers work full time like the formal set up, they are entitled to at least full wage, which is Rs20,000 in provinces and Rs25,000 in Sindh, along with other perks including social security, housing and old age employees’ benefits as per national as well as international laws.”

Quoting a precedent of Lady Health Worker’s case, he said the apex court had directed the governments to regularise and pay them full wage as they were working as fulltime employees.

In its recently judgment, the Supreme Court has ruled that employing teachers on a daily-wage basis and depriving them of pay protection and pension benefits is against fundamental rights and detrimental to the education sector.

A three-member bench heard a government petition against a Federal Service Tribunal (FST) judgment that had directed the government to provide pension benefits to dozens of school teachers by counting their service they had rendered as daily wagers.

The apex court upheld the FST decision: “appalled at this irresponsible, casual and utterly unprofessional approach of the policymakers towards a matter as important and as serious as education of our future generations.”

The verdict authored by Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan reads: “Article 3 of the Constitution provides that all forms of exploitation shall be eliminated. One of the reasons for which this becomes relevant to the present controversy is that notwithstanding the importance of the services they render to society, which have consequences for generations, the Respondents (teachers) were made to work under uncertain conditions on the pattern of unskilled and uneducated or semi-educated labour hired on a daily wage basis for seasonal projects expected to last for a limited period”.

Strongly deprecating, the judgment terms the actions of finance and education departments not only contrary to constitutional dictates but also contrary to the policy principles enshrined in the constitution which state that there has to be an equal adjustment of rights between employers and employees.

Models to be modelled

“Though, there are governance issues but non-formal schools have helped to bring out of school children to schools and improved literacy levels in Pakistan as well as countries in the region,” a Unicef official says.

“Considering the large size of the OOSC population in Pakistan, the expansion of Alternative Learning Pathways (ALP)/informal education is needed, as part of education provision integrated with a strong life skills component and community mobilization,” the official added.

“ALPs are a flexible means to provide education services to the most disadvantaged, including those from the poorest families, in remote and rural communities, in urban slums, for adolescent girls, children from ethnic minority groups, refugee, stateless and internally displaced children. ALPs, especially when integrating co-curricular and life skills activities, also cultivate competencies for social cohesion,” she said.

She said UNICEF also works with the four provincial governments to bring over 100,000 out-of-school children and adolescents, 60 per cent of which are girls, into education through over 5,000 ALP centers. The buildings of formal schools and madrassahs are used in the evening to conduct non-formal classes where teachers are paid as per minimum wage of the area.

Bangladesh’s BRAC Education Programme has been running schools to assist the most marginalised people in extremely poor, conflict-prone and post-disaster settings across five countries. Its learning models have been adopted by governments worldwide. About, 14 million children have graduated from BARC pre-primary and primary schools in Bangladesh.

Outside classrooms, their adult education and scholarship programmes, multi-purpose community learning centres, boat schools and mobile libraries have also increased access to learning and encouraged reading habits in the far-off areas.

Experts say school meals can attract and keep children at schools, improve their overall health and help them learn better. Recently, a grouping of more than 60 countries led by France and Finland has announced an initiative to ensure every child in need in the world gets a regular healthy meal in school by 2030. Five UN agencies have committed to assisting the School Meals Coalition, which is also committed to ‘smart’ school meals programmes, which combine regular meals in school with complementary health and nutrition interventions for children’s growth and learning.

“School health and nutrition programmes are impactful interventions to support schoolchildren and adolescents’ growth and development”, the UN agencies’ leaders said in their declaration in mid-November. “They can help to combat child poverty, hunger and malnutrition in all its forms. They attract children to school and support children’s learning, and long-term health and well-being.”

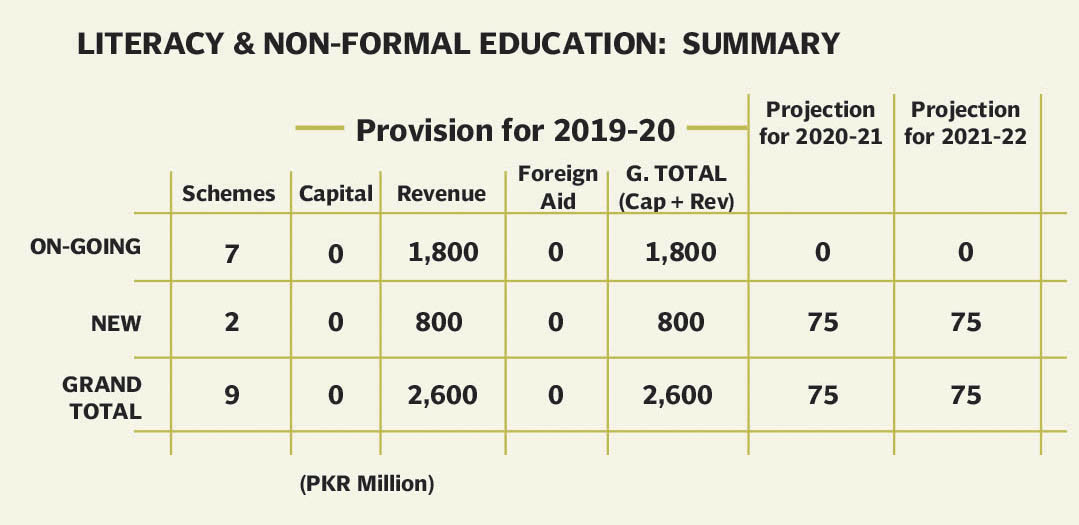

In Pakistan too, although the non-formal community schools are being run with the collaboration of private sector but hardly any serious collaborations were made to improve their conditions nor the government increased its spending.

According to Waseem Ajmal, Joint Secretary at Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training, the ministry has demanded a supplementary grant of Rs 155 million from the government to pay federally administered school teachers Rs 800 honorarium and Rs 2,500 utility bills. The proposal is in the process, he said, and may take a month or so for approval.

He said the schools will be allocated funds from recurring budget and not from development grants like the formal schools but the teachers will not be paid equivalent to formal teacher’s salaries.

He maintained since these teachers are not selected through proper criteria like the formal teachers so they are paid honorarium and not a proper salary. Some of them are may be highly qualified, he claimed, but not all are qualified like the formal teachers.

But the teachers argue 95 per cent of them are trained and hold a BEd and MA degrees, and even if they are not highly qualified, they don’t they deserve minimum wage of a labourer.

Now, the teachers are again planning to protest, said Namat Anjum, a representative of teachers from Bajaur, KPK, if their status remain unclear and their honorarium is not cleared and raised. “Even to get those paltry payments the teachers are forced to take to streets.”

Asma Ghani is an Islamabad based journalist. She has been reporting on social sector issues for over 12 years. She tweets @asmaghani11