Bushra Sohaib’s son Amin was two years old when she first began to notice his withdrawn disposition. Amin wouldn’t respond to his name and did not make eye contact. Bushra’s husband, General Sohaib Ahmed, who a was doctor at Karachi Shifa Hospital at the time, suggested that they take him to Aga Khan Hospital for a consult. There the couple was told that their son ‘seemed autistic’ – a term Bushra hadn’t heard of up until then. In Karachi at the time (in 2004) there were some therapists working with children with autism and were able to guide Bushra. However, a year after the diagnosis, Bushra’s husband was posted to Rawalpindi, and Bushra learned that there was little to no awareness and treatment for autism available in Rawalpindi as well as Islamabad.

“The good thing that came from being in Karachi at the time was that the awareness level was a lot better and Amin was diagnosed early,” said Bushra. “After the diagnosis, I spent the next six or seven years on the road all the time either driving to therapists or searching for them,” she added. Bushra over the course of the next few years was to spend a small fortune and many hours going to and from several therapists offices for assessments and therapies, often unsatisfied with the inadequate treatments and lack of commitment from professions offering their services.

After Bushra settled in Rawalpindi, she began meeting other parents with children who had also been diagnosed with ASD. She realised then that she wasn’t the only one struggling to help her child but that there was a deeper dearth of therapists or overall interventions for autism in Rawalpindi. Bushra was taking her son for speech therapy but realised that alone wouldn’t help him.

Ghazal Nadeem’s experience with her son Ali was somewhat similar. Ali was also about two years old when Ghazal began to notice some differences in his behaviour. Ali preferred to play by himself and spent hours lost in his own world where he enjoyed activites such as lining up his toys in a neat row. Ghazal began to feel that Ali didn’t like to communicate his thoughts and feelings with her, the way her older daughter did when she was Ali’s age and that Ali preferred to play by himself rather than with other kids.

Ghazal who was from Rawalpindi was soon to learn that her son had what is known as autism. However, the doctors in Rawalpindi were unable to guide her much more beyond that and the early years of intervention through myriad of therapies that could have helped equip Ali better for his condition were unfortunately lost. Six years later, Ghazal’s second son was also diagnosed with autism.

“As you know with autism, communication isn’t the only deficit. There’s many other issues that have to be dealt with. For example, their socialisation, self-help, academics, cognition and communication too. Then their sensory issues and their behavioural issues also need to be tackled,” she said. However, without proper guidance offered from doctors and lack of available therapies, Ghazal was at a loss for how to help her sons. “Speech therapy alone can’t cover all of these issues and that early intervention period of theirs was wasted.”

During this time Bushra moved to Rawalpindi where she met Ghazal as well as other parents whose children had also been diagnosed with autism. When more and more cases of autism began to be diagnosed in Rawalpindi and adjoining areas, the parents began to put together a network and soon Bushra, along with her husband, registered Autism Society of Pakistan as a not-for-profit and began offering subsidised treatments and therapies through the organisations to other parents with children diagnosed with autism. The guidance and treatment they felt should be offered at the earliest so a child can better equip him or herself up to deal with some of the challenges that come with autism. “These individual isolated therapies, they are not helpful at all for autism. You need an entire intervention plan and then you see improvement in children,” said Bushra, who is now the CEO of the not-for-profit that currently has 100 children enrolled in their school who have been diagnosed with autism. Ghazal is also now the Director of Autism Society of Pakistan Rawalpindi.

“Autism Society of Pakistan was registered in 2010. The purpose was to provide support to kids affected with autism as well as their parents because affected parents are the ones whose efforts led to the creating of this organisation,” said Ghazal. “The purpose was to help those parents who were struggling with their children’s diagnosis and treatment as even in bigger cities like Karachi or Rawalpinidi they didn’t have these services available for their children, she said. “We saw that there’s not enough awareness even in bigger more metropolitan cities and there’s no guidance anywhere. Therefore, we thought a facility should be created where under one roof these kids should also have a rehabilitative programme as well as a place where their parents can be provided support as well.”

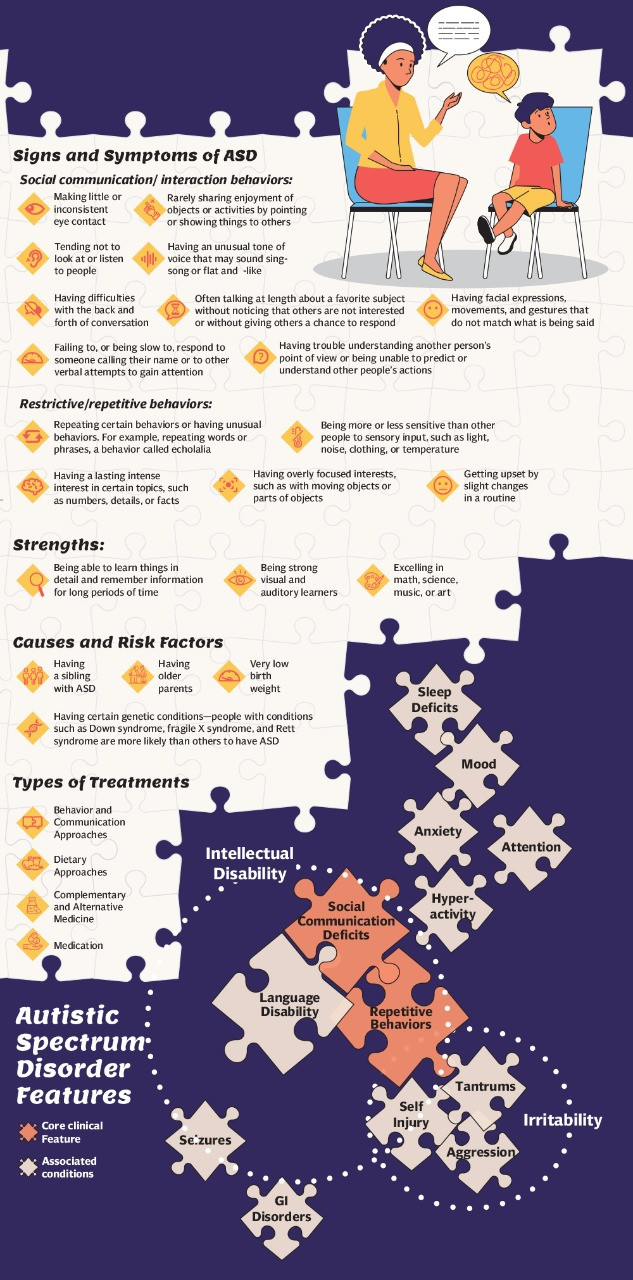

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association changed the term ‘Autism’ to ‘Autistic Spectrum Disorder’ (ASD). The purpose for the umbrella term was to cover the autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder and Asperger syndrome. According to the Cleveland Clinic’s definition people with ASD may have difficulty conducting “social interactions, interpretating and using non-verbal and verbal communication in social contexts.” Cleveland Clinic also lists the following signs that may indicate that a child could be at risk for autism: if a child that doesn’t respond to their name being called at all or responds inconsistently, if a child doesn’t smile widely or make warm, joyful expressions by the age of six months, if a child doesn’t engage in smiling, making sounds and making faces with you or other people by the age of nine months, if a child doesn’t babble by 12 months, if a child does not use back-and-forth gestures such as showing, pointing, reaching or waving by 12 months, does not use words by 16 months and does not use meaningful, two-word phrases (not including imitating or repeating) by 24 months or regresses ie losing of speech, babbling or social skills at any age.

Since research and documentation on ASD in Pakistan is limited, it is hard to estimate how prevalent the disorder is in the country. However, according to a Pakistan Country Report by National Institute of Special Needs Education on the prevalence of autism in Pakistan, the cases of autism are estimated to be one in 500. Based on this estimation, it is probable that the number of people in the country who are on the spectrum is 345,600. Pakistan Autism Society also has cited a similar number with 350, 000 children in Pakistan having ASD. However, this number in reality could be much higher since cases are under reported, misdiagnosed or often even concealed due to social stigma. According to data released by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in April 2018, 1 in 59 children in multiple communities in the United States had been identified with ASD. Based on this figure, it can safely be presumed that with proper diagnosis, the reported figure of children with ASD could be far higher in Pakistan.

For children with ASD, the sooner the condition is diagnosed the better. Speech therapy, along with developing communication skills in the form of signing and picture/symbol cards, especially before the age of three, can go a long way in helping the child develop communication skills. However, a broader treatment programme should factor in social, emotional and physical development based on the child’s age and needs.

The problem with awareness in regards to autism however, seems to be a wide one and the gap in treatments seems to be nationwide. A study of 15 mothers from Karachi hailing from upper- and middle-class families with children diagnosed with ASD conducted by Juveriah Furrukh and Gulnaz Anjum in 2020 titled, ‘Coping with autism spectrum disorder in Pakistan: a phenomology of mothers who have children with ASD’ reported similar findings. The study revealed that five of the 15 mothers had not heard the term autism before their child was diagnosed with the condition. A mere two of them were explained by their doctors about the condition whereas seven out of the 15 had to research and learn about the disorder thereafter the diagnosis, themselves. Almost all of the mothers in the study also shared their frustration at the lack of available therapies in Pakistan.

According to Special Needs Education Teacher Juveriah Furrukh who teaches children aged between five and six years who have been diagnosed with autism, “There is unfortunately a narrative in mainstream schools that ‘yeh bacha normal nahi hai’ (he is not normal).”

Farrukh explains that over the course of her time teaching as a special needs teacher she has observed that even in special needs inclusive schools both teachers - and even principals in some cases - are either not empathetic and supportive or even fully aware of the condition. This is due to the fact that teachers are not always fully qualified to teach students with ASD or other learning disorders and are only given trainings periodically after they’ve been hired and in some cases, even principals have displayed lack of professionalism and even gone to the extent of ridiculing children who have ASD.

Moreover, Farrukh reveals that lack of awareness can sometimes exist at both parallels where either a teacher with a poor grasp of autism ends up critiquing a child for attributes that are part of his ASD such as complaining that their child ‘doesn’t talk or participate in class’ or where parents who know that their child has been diagnosed with ASD and are either in denial about the diagnosis or haven’t taken them for therapies. “There is a lack of awareness and there’s a lack of acceptance,” she adds.

“A lot of parents of my ASD students mention that their kids are not invited to birthday parties of other kids in their class,” she added. “One parent also mentioned that teachers can sometimes be rude or condescending to their child who has ASD.”

The differences with autism

The trouble that has often been with diagnosing ASD is the condition presents itself differently in people. Juveriah explains, “The same way that no two neurotypical kids are the same, no two kids with autism are the same either. It’s a spectrum and all of them have different diagnosis. Every single one needs different types of therapy. Some need remedial therapy whereas some don’t. That’s how it works.”

“For instance, one of my students [with Autism] is very vocal and friendly and he announces himself when he enters the classroom in the morning. On the other hand, another student in my class who also has ASD, she is extremely strong academically but she won’t speak in class,” she said. “A third student in my class with ASD, he is a bit irregular so any progress that we make with him, for instance increasing his sitting tolerance or his classroom time, when he is absent for a long period of time such as three weeks, ends up being lost and we’re just back to square one.”

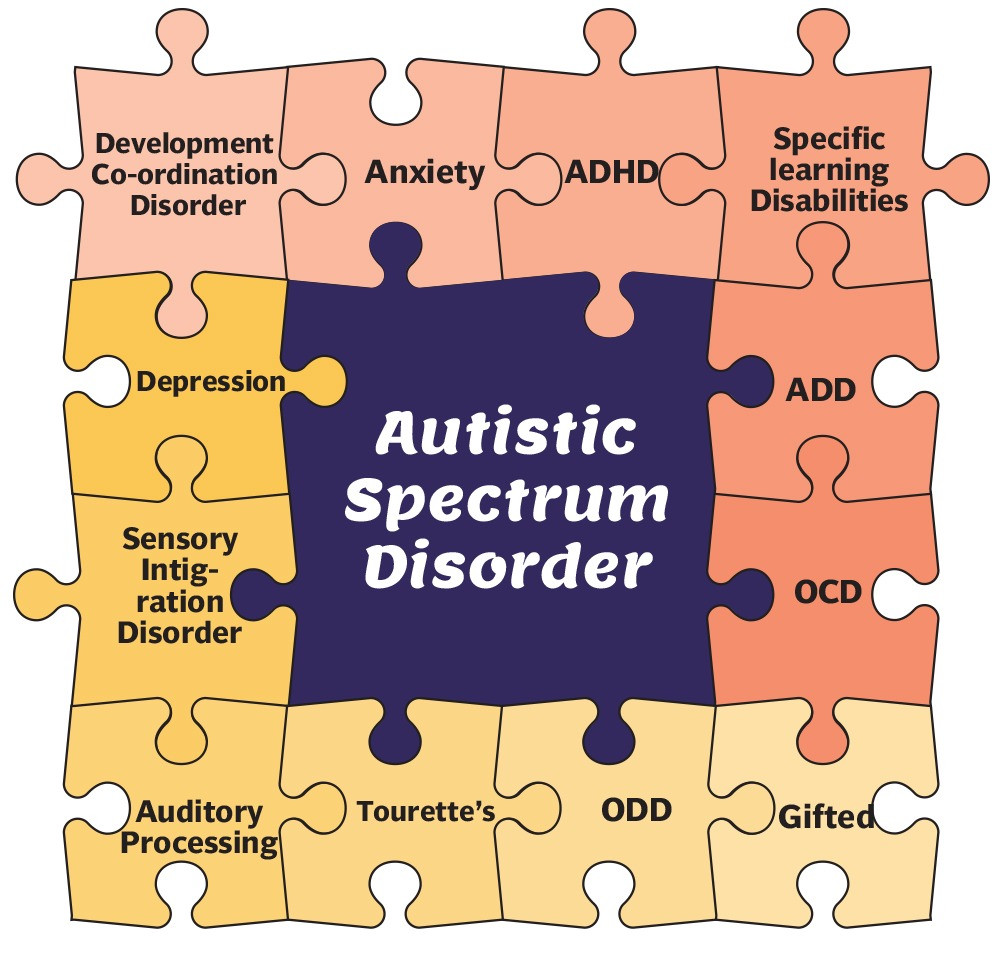

Another common diagnostic mistake when it comes to ASD is that it is often misdiagnosed as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is another common neurodevelopmental disorder found in children. Children with either condition experience trouble communicating and focusing. However, the two conditions are vastly different.

For instance, a child with ADHD will exhibit symptoms such as becoming easily distracted, frequently jumping from one task to another, difficulty focusing, concentrating and narrowing attention to one task, talking nonstop and hyperactivity. A child with autism on the other hand, will present symptoms such as being unresponsive to stimuli, intense focus and concentration on a single item, avoiding eye contact, withdrawn behaviours and delayed developmental milestones.

However, there are cases where a child can have both conditions. According to the CDC, 14 per cent of children with ADHD can also have ASD. Moreover, according to a study from 2013 cited by Healthline, those children with both conditions had more debilitating symptoms that children who didn’t exhibit ASD traits. More specifically, children with ADHD and ASD symptoms are more likely to have learning difficulties and impaired social skills than children who only have one of the conditions.

According to a study conducted by Sana Khan, Rashid Qayyum and Javaid Iqbal for the Armed Forces Institute of Mental Health/National University of Medical Sciences Rawalpindi Pakistan, Pak Emirates Military Hospital titled, ‘Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders among adult psychiatric patients reporting at a tertiary care hospital’ that tested 1,889 adult patients, 8.6 per cent tested positive for ASD and 11 per cent were positive for ADHD. Moreover, ten of the patients had both ASD and ADHD.

The study concluded that there was a high prevalence of ASD and ADHD among the adult psychiatric patients of Pakistan. More notably, low education was also found to be consistent with presence of ASD and ADHD in this study. However, it is important to note that low education can be an imminent consequence of the two disorders as children with either one are unable to achieve education milestones. The study however, also revealed that illicit substance use can either contribute in the causing the disorder as well as poor response to treatment. It was also concluded from the study that 19 per cent of the target population met the criteria either for ASD or for ADHD.

Another hurdle in diagnosis as well as reporting of autism in Pakistan are the societal taboos or misperceptions that surround the disorder. Another finding of the ‘Coping with autism spectrum disorder in Pakistan’ study was that many of the mothers who were part of the study revealed that they were blamed for their children’s autism. Family members and in-laws often blamed the mothers for the child’s condition, for instance someone’s diabetes being cited as a reason the child’s autism or in one case the mother’s ‘sins’ being supplied as an explanation for the child’s disorder. Out of the 15 mothers, nine of them also reported that their husbands were unable to deal with child’s emotional needs.

With little awareness of ASD on a national scale and a lack of expertise offered by the doctors in Pakistan, children and their parents are left to their own devices to deal with autism. Moreover, in lieu of a mental health policy that can help healthcare providers flag the condition early on in childhood and then subsequently provide necessary guidance to parents, the disorder will continue to go undetected and untreated. The lack of acceptance of the condition also stems from a lack of understanding of the disorder, thus making it harder for people with ASD to assimilate and be accepted by society too.