Kabul is worried – and for obvious reasons. The ‘protecting power’ is withdrawing while an ascendant Taliban are advancing on Kabul. Fears run rampant that Afghanistan might descend into bloody chaos post-US exit. President Ashraf Ghani, however, says the “narrative of gloom and doom must stop” because “we are defensible”. Call it hubristic pride at best, or self-deception at worst, for US forces are halfway through their withdrawal and dozens of Afghan districts have already fallen to the Taliban. In most districts, it was an easy walkover. The Ghani administration is seeking to externalise the blame. And in Pakistan, they find a favourite whipping boy.

“Today, the Taliban control more Afghan territory than they had ruled before the toppling of their regime in 2001. What was the point of 20-year US mission in Afghanistan,” asks one security official. Early staunch US supporters are now disillusioned. A former Afghan president said in a recent interview that the US came to Afghanistan to fight extremism and bring stability and is leaving 20 years later having failed at both. “Their legacy is a war-ravaged nation in total disgrace and disaster,” Hamid Karzai told The Associated Press earlier this month. “Extremism is at the highest point today,” he said while questioning the objectives of the two decades of war in his country.

IS-Khorasan’s emergence

Creative: Mohsin Alam

“It’s perplexing that when tens of thousands of US-led Nato troops and hundreds of thousands of Afghan forces were fighting the Taliban, a new terrorist group emerged out of the thin air: the Khorasan franchise of Islamic State,” another official says. “How did this happen under the watch of US intelligence and military in Afghanistan?”

IS-Khorasan emerged to challenge the authority of the Taliban founder, Mullah Muhammad Omar, who was revered as Amirul Momineen (leader of the faithful) of the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan”. IS-Khorasan was cobbled up by militants, led by Hafiz Saeed Orakzai and Abdullah Orakzai, in Afghanistan towards the end of 2014. A large number of militants from the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and district chiefs were its first recruits. Its emergence coincided with a decisive Pakistani military operation against the TTP and its affiliates in the regions along the Afghan border. Tellingly, hundreds of Indians from the southern state of Kerala discreetly travelled in batches to Afghanistan between 2016 and 2018 to join the ranks of IS-Khorasan. This massive “recruitment” showed complacent incompetence of India.

IS-Khorasan had declared a “mini caliphate” in eastern Afghanistan where it enjoyed safe haven together with TTP terrorists who had fled the military operation in Pakistan. The group was primarily fighting the Taliban and occasionally targeting the Hazara Shia minority. In the past, the Taliban had repeatedly accused the Afghan government and the US of harbouring IS-Khorasan and coming to its rescue whenever its fighters came under Taliban siege in Nangarhar and Jauzjan provinces.

“…weapons are often transferred to the [IS-held] territory of Afghanistan by helicopters without identifying insignia. With the US and Nato fully controlling the skies over Afghanistan, there is every reason to believe they had a hand in that, or at least, did not hamper these flights,” The Economic Times wrote in an April 22, 2019 report. Two years earlier, Karzai also said he had “more than suspicion” that the US bases “were being used" to support IS-Khorasan. “[Afghan people have told me] how unmarked, non-military coloured helicopters supply these [IS] people in not just one, but many parts of the country,” Karzai told Russia’s RT in an October 2017 interview quoting multiple sources. “We have the right to ask these questions and the US government must answer.” Russia and Iran have also accused the US of supporting IS-Khorasan’s rise

The Taliban’s ongoing lightning territorial gains should not come as a surprise. They already have had parallel administrative, judicial and security set-ups in most of the country with shadow governors ruling the provinces in the name of the ‘Islamic Emirate’. The Taliban captured the ancestral home of President Ghani in Logar province earlier this month. In a tweet, the militia revealed that the peasants tilling the Afghan leader’s farmlands have long been paying them ‘land tax’. This raises serious questions about the protracted US campaign in Afghanistan.

Herculean task

Surprisingly, most of Afghanistan remains lawless, but the Kabul administration seeks to blame Pakistan for sheltering the Taliban, with its foreign backers pressing Islamabad to do more. “We have done everything on our side of the border,” the security official says. “The state had its writ in only 37% of the tribal belt before Operation Zarb-e-Azb. But today, every inch of the region is under the state’s control,” he adds while referring to the 2014 military offensive that convincingly defeated the terrorists hiding there.

Moreover, the Pakistani military undertook the gigantic task of fencing the long border with Afghanistan in an effort to plug the holes used by terrorists to sneak in and out.

“A 2,611-kilometre fence along the Afghan border is almost complete, while 45% of the 909-kilometre fence along the Iran border has been erected,” the official says. “The border will be dotted with 843 forts and outposts for better monitoring and surveillance – 450 of them have already been built,” the official adds. “However on their side, the Afghan security forces have done nothing to secure the border.”

Kabul was [and still is] opposed to the fence. The idea didn’t impress the Americans either. The enormous financial cost of the project was also a huge concern. But army chief Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa chose to defy the odds. The fence has helped to transform security in Pakistan, sharply cutting terrorist attacks.

Military officials say the TTP uses safe haven inside Afghanistan to orchestrate attacks inside Pakistan. At the Feb 2018 Munich security conference, Gen Bajwa said Pakistan was being attacked from terrorist hideouts on Afghan soil. “Out of the total 131 terrorist attacks in Pakistan [that year], 123 had been traced to Afghanistan,” the official recalls him telling the participants.

They also believe that the Indian and Afghan intelligence agencies are colluding to arm, train and bankroll terrorist groups, including the TTP, for destabilising Pakistan. “RAW has infiltrated NDS,” the security official says. “Kabul uses India as a bogey because it knows that Pakistan has serious concerns about Delhi’s outsized Afghan footprint.”

Kabul’s elusive strategy

Pakistan has always said that there is no military solution to the Afghan conflict. “The US-led mission, on the other hand, never had a clear strategy. First, they pushed for a battlefield victory; then they tried to beat the insurgents into negotiations before finally settling for talks on the Taliban’s terms,” the official says. “Kabul, on its part, appeared to have little interest in a negotiated end to the insurgency.”

The High Peace Council, which was set up in 2010 to negotiate with the Taliban was dissolved by President Ghani in 2019 and a State Ministry of Peace Affairs was set up instead. A year later, the High Council for National Reconciliation was formed to resolve the 2020 political deadlock on elections between President Ghani and his challenger Dr Abdullah Abdullah. Later it was also mandated to decide whether Kabul signs a possible deal with the Taliban. “What did the councils achieve? Zero, zilch,” the official says.

Afghan officials blame Pakistan for harbouring the Taliban as a strategic asset. “Pakistan operates an organised system of support. The Taliban receive logistics there, their finances are there and recruitment is there,” President Ghani alleged in a May 2021 interview to Germany’s Der Spiegel magazine. The “irresponsible and baseless” allegations triggered a strong diplomatic protest from Islamabad.

“Pakistan has been hosting millions of Afghan refugees since the early 1980s. They easily travelled between the two countries. Some Taliban might have taken advantage of that to sneak in,” says the official. “But let it be clear that the Taliban have no organised support in Pakistan.”

Pakistan shares huge borders with India, to the east, and with Afghanistan, to the west. A two-front hostile neighbourhood has always been a nightmarish scenario for its security establishment who in the past sought to have a friendly government in Afghanistan. But Prime Minister Imran Khan said in a June 4, 2021 interview that his government had changed the decades-long policy. “Any Afghan government chosen by the people is who Pakistan should deal with,” he told Reuters. “Pakistan should not try to do any manipulation in Afghanistan".

Post-US exit scenarios

Pakistan has been pushing for a political settlement before the US exit. But peace talks have failed to match the pullback pace. And the Taliban are taking advantage of the situation by mustering as much territorial gains as possible. “It’s a near-repeat of the 1980s. Afghanistan is again on the cusp of civil war. The US is leaving behind a mess, perhaps as a strategic move to create volatility in the region,” the official says.

There could be two scenarios after the American pullout: a Taliban takeover or civil war. “Pakistan would suffer the most, after Afghanistan itself, if there is civil war and a refugee crisis [ensues]. And then there would be pressure on us to jump in and become a part of it,” PM Khan said in the Reuters interview.

A Taliban takeover would also have implications for Pakistan. “This might embolden other militant groups who could potentially destabilise the entire region,” the official says. “A stable Afghanistan is in the interest of all countries in the region, including China and Russia,” he adds. “Chaos in Afghanistan will spill over into Pakistan, which would affect the multibillion-dollar China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).” China wants to see CPEC, which is part of its Belt and Road Initiative, extended to Central Asia to connect the entire region. Only a stable Afghanistan could ensure such regional connectivity.

Shifting strategic interest

It’s clear now that the US strategic interest has shifted to containment of China. A flurry of recent American moves, including its effort to revive the four-nation Quad alliance, and the statements from G7 and Nato summits, make it amply clear that the US is making new geostrategic realignments against China. PM Khan revealed in a CGTN interview earlier this month that the US was also putting pressure on Pakistan to downgrade its China ties. “It is very unfair for the US or other Western power to pressurise countries like us to take sides in their conflict with China,” he said.

The Pentagon expected Pakistan to host a small “on-call” US force which could carry out counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan, should the need arise. But PM Khan said Pakistan would “absolutely not” do that because “we can be partners [with the US] in peace, but never in conflict”. This blunt refusal might have upset the Joe Biden administration, and officials say they know it could have consequences for Pakistan.

Mainstreaming of ex-FATA

The Kabul administration is trying to stoke ethnic tension in Pakistan’s Pashtun-dominated areas. President Ghani’s public statements in favour of Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) are seen by Pakistan as blatant interference in its internal affairs. “PTM is playing in the hands of RAW and NDS – the two hostile agencies that seek to exploit ethnic fault-lines in Pakistan, be it in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa or in Balochistan,” says the official. “The PTM uses ethnicity and language to promote a sense of marginalisation among the Pashtuns,” he adds. “This claim is preposterous! The Pashtuns are the second largest ethnic group in Pakistan’s armed forces.”

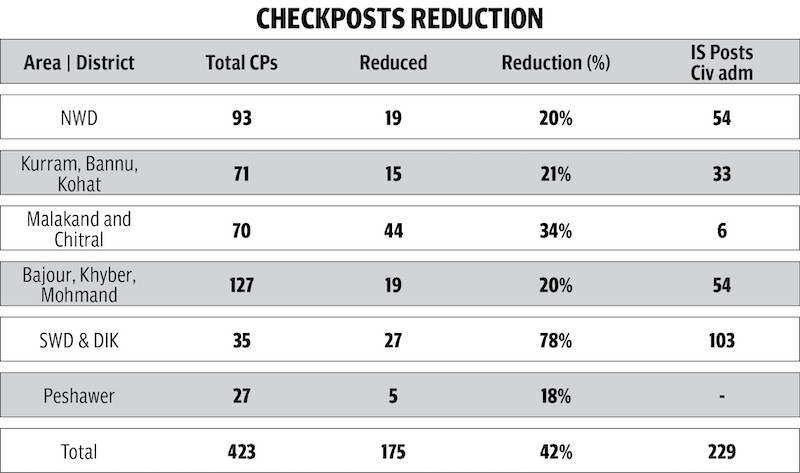

The PTM also seeks to cash in on the grievances of the tribespeople. Some of these grievances are genuine. It is natural to have such grievances in a region where the military has fought a major battle against terrorists. The seven tribal agencies [now districts of K-P] were disinfested and handed over to civil administration under the military’s ‘clear-hold-transfer’ strategy. “The TTP terrorists had rigged these regions with landmines, but demining operations are ongoing there,” the official says. “The number of security check-posts has also been reduced considerably.”

The former tribal agencies – the Waziristan region in particular – have seen an uptick in targeted killings. Some elements are using the violence to stoke unrest. “These are sporadic incidents which happen everywhere, in almost every city. The people have old tribal and family feuds, and land disputes,” the official says. “Giving it a twist to malign the state institutions reeks of sinister designs.”

Not everyone is happy with the end of the old system. Some people find it particularly hard to reconcile with the change. The mainstreaming of ex-Fata is a huge achievement. Terrorism has been eliminated, the state’s writ established, and the infrastructure development process ongoing. The official claims that some of these regions are now even better than rural Sindh and Punjab. But he admits the development pace leaves much to be desired.

Critics say endemic infighting in PTI’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa has stymied the development process in the tribal districts. “The chief minister should have been proactive in order to assuage the grievances of the tribespeople,” says one government official. “You would have rarely seen him travelling to North and South Waziristan or other tribal districts.”

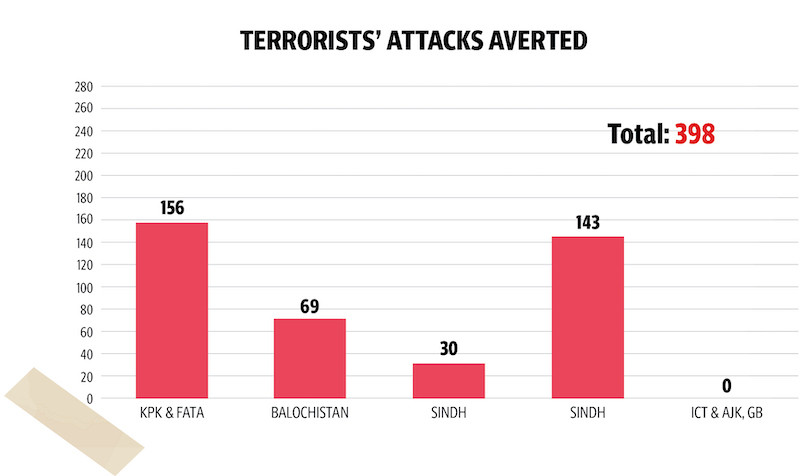

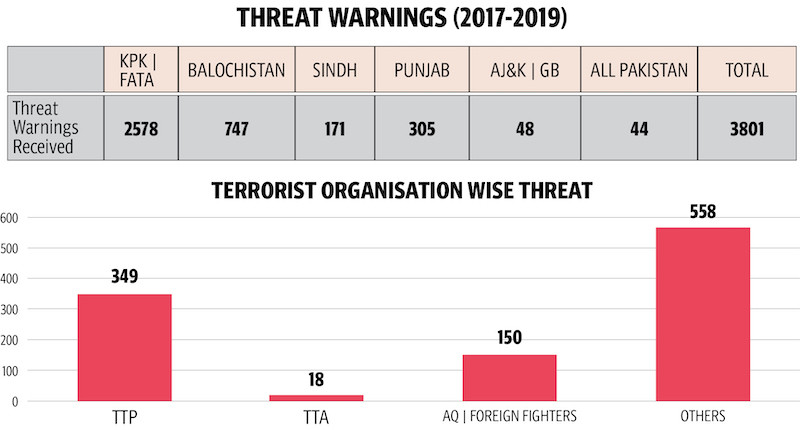

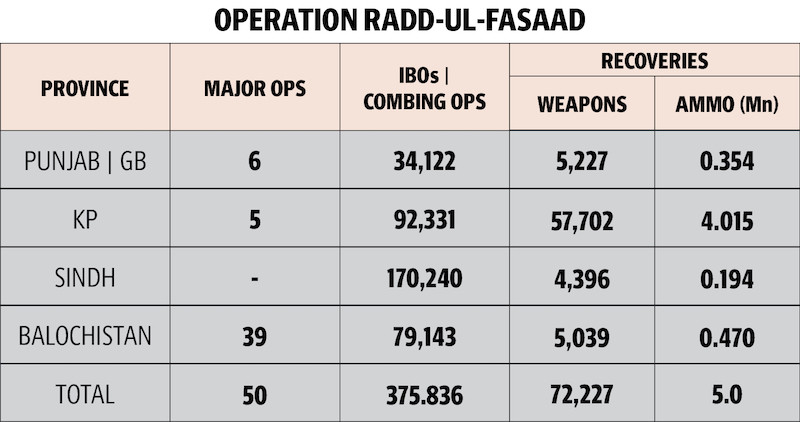

The urban purge

In February 2017, the military initiated operation Radd-ul-Fasaad to disarm and eliminate the terrorist sleeper cells across the country, especially in the urban centres. Thousands of intelligence-driven raids were conducted against terrorist financers and sympathisers and hundreds of terror plots were smashed. “These operations resulted in a visible drop in sectarian violence in the country,” says the official. “The burning of Madrassah Tahleem-ul-Quran in Rawalpindi in 2013 was the last major communal attack in the country,” he adds.

However, critics regret the lack of political will on the part of civilian government to fully implement the 20-point National Action Plan – a comprehensive strategy put together in Jan 2015 to eliminate terrorism and extremism from society.

Pakistan has paid a huge price in blood and treasure for its fight against terrorism. No doubt, the situation is far from ideal. But it’s unfair to scapegoat Pakistan for the fatally flawed US strategies and incompetence of Afghan kleptocracy. A former US defense secretary very aptly summed up the situation in Afghanistan. “… the corruption, incompetence, and infighting among officials in Kabul, the provinces and the districts left many ordinary Afghans indifferent, or hostile, to the government,” Robert Gates wrote in a June 13, 2021 opinion piece in The New York Times.

Old habits may die hard and the temptation to find a scapegoat elsewhere may be irresistible. But lasting positive change in Afghanistan will remain elusive until all stakeholders honestly reassess their own part in the present morass.