There is more to wildlife conservation than meets the eye. On the surface, much of it appears to the mass public as focused towards individual species on the brink of extinction, and for good reason. Using handful of ‘enigmatic species’ as they are called – your pandas and tigers and rhinoceroses, etc. – conservationists are able to canvas mass support for saving entire ecosystems and restoring a balance to nature. In some cases, in fact, saving one keystone species can cascade into a chain of natural events that work towards environmental betterment.

Pakistan has been blessed with its own enigmatic species, each more mysterious than the next. In the north we have the elusive snow leopard, rarely caught on film. The mighty Indus is home to another, even more puzzling creature – the blind Indus River Dolphin, known locally as Bhulan.

It’s distinct eyeless form, that appears in many ways contrary to popular conception of dolphins, is one overt reason for why it has captured the imagination, but so are the many myths that circulate around it in folklore. Its sister species in the Ganges is already considered an emblem of the namesake river goddess in Hindu mythology. But for us, perhaps the bigger question is how a dolphin came to call a river a home in the first place.

But mysteries aside, there has been in recent years a visibly upward trend in the rare dolphin’s population, according to the researchers dedicated to studying it.

Encouraging signs

There was once a time when the Indus River Dolphin was ubiquitous in not just the river it takes its name after but all connected waterways. Speaking on the matter, Indus Dolphin Conservation Centre (IDCC) Sukkur Incharge Mir Akhtar Talpur said the species started moving towards endangered status when the South Asian irrigation system was built by the British in the 18th century. “As the many dams and barrages were constructed to cater to the needs of the agriculture sector, this aquatic mammal’s natural range was disturbed and it was confined between one riverine structure and another,” he explained.

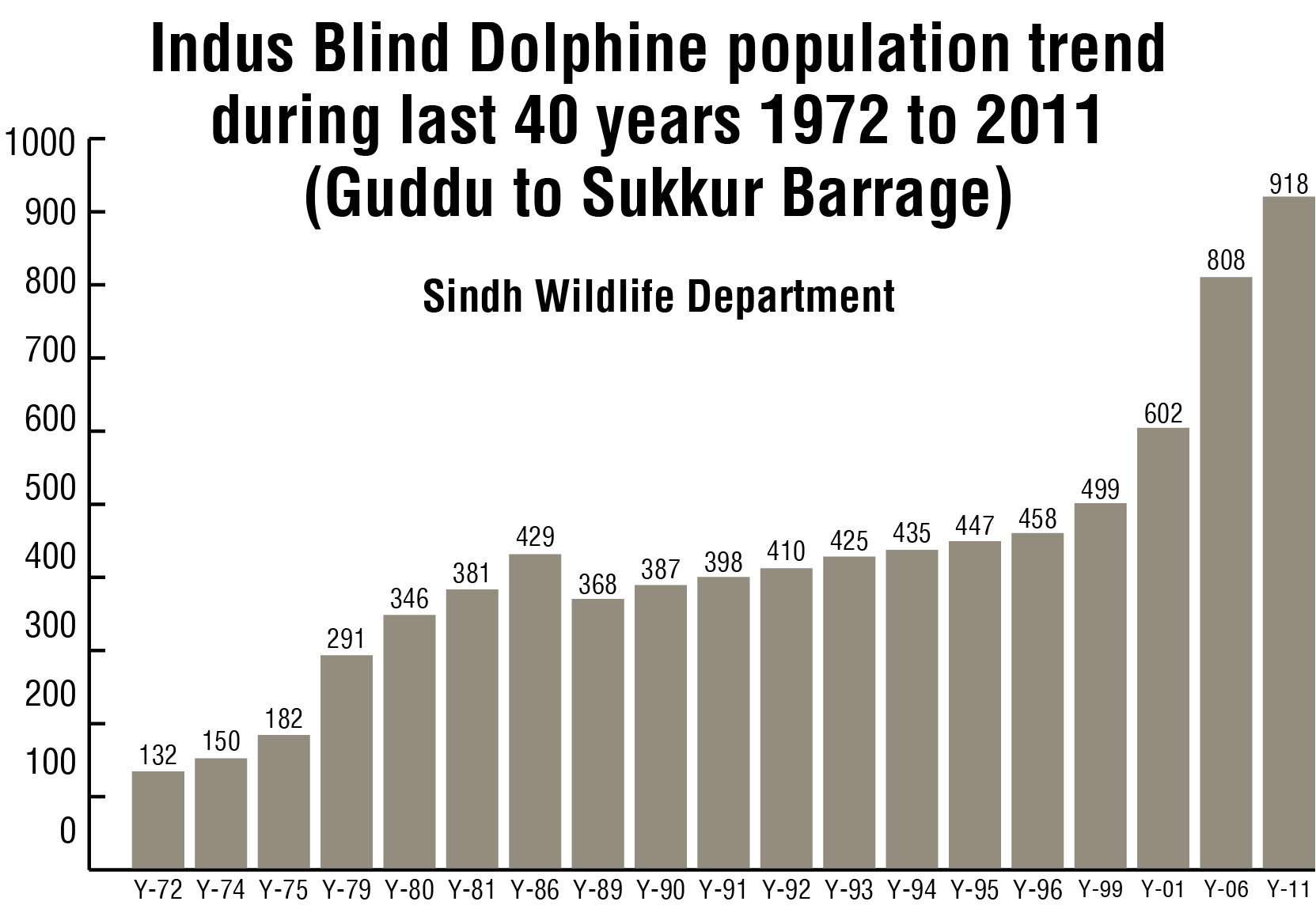

Talpur said the authorities started officially monitoring the numbers of the endangered dolphin with the establishment of the Sindh Wildlife Department in 1972. “The department started routine surveys and since then, we have know the exact numbers of the dolphin in Sindh.”

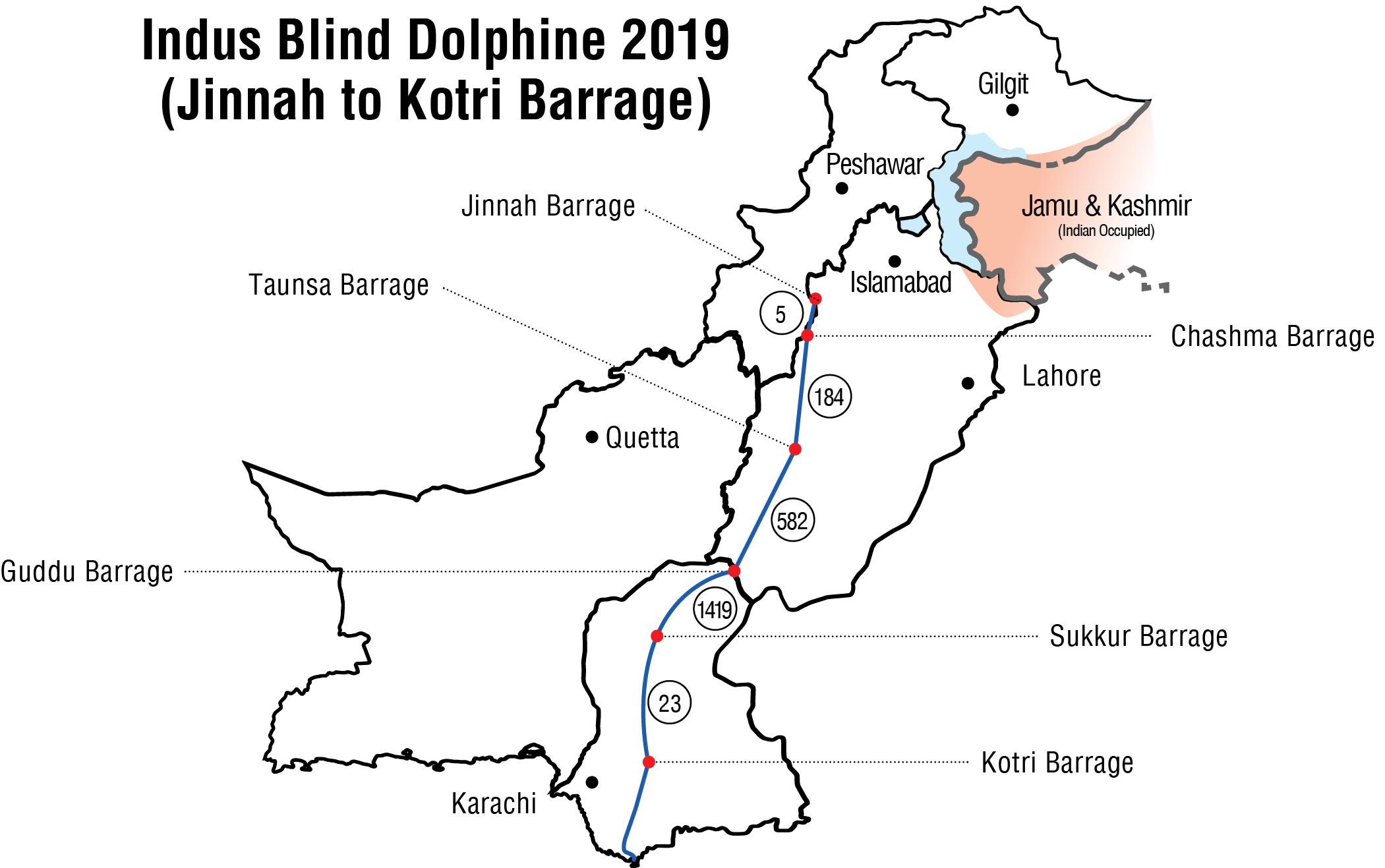

In 1972, when the first survey was carried out, there were just a paltry 132 dolphins in Sindh. “Even so, there has been a steady increase ever since,” Talpur shared. “A 1975 survey showed the numbers had grown to 182. When the last survey was conducted in 2019, we found there were 1,419 river dolphins between the Guddu and Kotri barrages.”

World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Project Manager for Sukkur Mohammad Imran Malik said that his organisation’s own independent surveys and rescue operations supported the steady rise in dolphin numbers. “Our results have consistently indicated an increase in this endangered species’ population. We know the numbers have been growing since 2001 and it is quite possible this trend began in the 1970s, when the hunting of this animal was banned,” he said.

Sharing the results of their latest survey, Malik said dolphin abundance was increasing between the Chashma and Taunsa barrages, a range where the species population was previously thought to be stable. “Direct counting results for the sub-population between Chashma and Taunsa barrages were 84, 82, 87 and 170 for the years 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2017 respectively,” he shared. “Between Taunsa and Guddu, similarly, direct counts have been steadily rising from 259 in 2001, to 465 in 2011 and 571 in 2017.”

“The last sub-population surveyed between Guddu and Sukkur barrages, which historically hosted the highest population of the Indus River dolphin also indicated a similar significant increase in population from 602 in 2001 to 1,075 in 2017,” Malik added.

Fruits of collective effort

According to Talpur, the fishing communities living along the banks of the Indus, particularly the Hindu Bagri community, used to hunt the dolphins back in the day to extract oil from its fat. “They used this oil to cook food, but an awareness campaign initiated by the Sindh Wildlife Department and WWF convinced them and other stakeholders to start taking care of the endangered species,” he said. “Because of this extensive work, members of the riverside communities immediately inform concerned officials if they sight a dead or stranded dolphin,” he added.

WWF’s Malik provided further detail on this participatory approach to wildlife conservation. “We integrate research and effective law enforcement with stakeholder and community engagement,” he said. “Our joint dolphin rescue programme with the Sindh Wildlife Department has been in place since 1992 and has been very effective in rescuing any stranded or trapped dolphins,” he added. Sharing rescue figures, Malik revealed that 131 out 147 stranded dolphins were saved and released back into the river between 1992 and 2017. “Only one specimen could not survive the rescue operation, while 33 could not be rescued at all.”

WWF and the Sindh Wildlife Department have also established a dolphin-monitoring network in collaboration with relevant stakeholders and local communities to monitor the Indus River and adjacent canals and tributaries to save dolphins from other hazards. “The monitoring teams of this network have conducted over 100 monitoring surveys since 2015 to stop illegal fishing and to rescue stranded dolphins with 12 successful rescues during 2016.”

Talking about the steps taken to protect the endangered species, Malik said that a 24-hour phone helpline has been set up to report any stranded dolphins. “The observed increase in the population may be an outcome of all these concrete and continuous efforts,” he said.

Threats persist

According to WWF researchers, habitat fragmentation and degradation due to extraction of water in the dry season and pollution are amongst the prime threats faced by the Indus River Dolphin. Since the 1870s the range of the Indus River dolphin has been reduced to one-fifth of its historical range, primarily due to shortage of water caused by agricultural demands and removal of water from the river to supply the extensive irrigation system in Pakistan.

“Barrages across the Indus River hold running water and divert it into an extensive network of irrigation canals emerging from each barrage to fulfill the need of water for agriculture,” shared Malik. “Indus dolphins tend to move to irrigation canals through flow regulator gates, adjacent to barrages throughout the year and when the canals are closed for maintenance, dolphins are stuck in the canals due to sudden water shortage.”

The WWF official said intensive fishing in the core habitat of the Indus dolphin is also one of the key threats to its population with high probability of dolphin mortality from entanglement in fishing nets, especially when they move into easily accessible and heavily fished irrigation canals. “Habitat fragmentation and degradation due to extraction of water in the dry season and pollution are amongst the prime threats faced by the Indus River dolphin,” he added. “The construction of numerous dams and barrages across the Indus River has led to the fragmentation of the Indus River dolphin population into isolated sub-populations, many of which have been extirpated especially from the upstream reaches of the river,” he concluded.

Talking about the low number of dolphins in Punjab, Talpur claimed that most of the big cities of Punjab are situated at the bank of rivers and all the drainage waste is mercilessly released in the river. “Not only this but industrial waste, especially poisonous waste from tanneries, is extremely hazardous for the fragile mammal,” he said. According to him, in Sindh from Guddu barrage to Sukkur barrage, no big cities exist at the bank of Indus, except for Sukkur.

“Yet another reason is scarcity of water in the upstream and downstream from Guddu to Sukkur barrages,” he added. “Ample water is available throughout the year, which is why majority of the blind Indus dolphins are found between the two barrages. The only time of the year when the dolphins face difficulties in surviving is in January during the closure of barrages for annual repairs and maintenance in January.” During those days, cases of dolphins slipping in the canal in search of food are frequent. Upon reports of trapped dolphins, they are rescued and released in the safety of the river.

Talking about the fragility of the dolphins Malik said, “They suffer heart attacks as soon as they are entangled in the fishing nets. Therefore, the fishermen are educated to immediately make efforts to rescue the mammal to save its life.”

Mehram Ali Mirani, an elderly fisherman, strongly condemned the use of poisonous chemicals by some in his trade. “This practice must be stopped because on the one hand it proves hazardous for the marine life and on the other human beings also fall prey to various diseases after eating those poisonous fish,” he said. “We are born fishermen and our survival is linked to the clean and healthy river. Therefore, I request the fishermen community, not to use chemicals to catch fish,” he said.