The Pakistan Democratic Movement has died an unceremonious death. While the Pakistan Peoples Party rang the death knells, the Awami National Party wrote the sorry epitaph to the opposition alliance that whipped up a political storm, which, at one stage, threatened to sweep away the beleaguered government.

For its supporters, the PDM’s demise must be painful because nobody gave a eulogy to celebrate its six-odd months’ momentous struggle to “wrest back civilian control of power”. More painful must be the ongoing rancorous exchanges and verbal dueling among the opposition politicians who had had each other’s backs until recently. The rare bonhomie has quickly vanished into thin air. And souring relations have laid bare old scars and reopened unhealed wounds.

The PDM’s undramatic collapse – not even conceivable only a few weeks ago – has left many scratching their heads about what went wrong with the alliance that had brought together 11 disparate parties to put up a formidable challenge to the government of Imran Khan, which they considered as an appendage of the miltablishment. The PDM was a potpourri of right-wing politico-religious groups, centrist and left-of-centre mainstream parties as well as secular nationalists. This inclusivity was its strength – and later turned out to be its weakness. Supporters hailed it as a new political awakening to win “true democracy” in a country where praetorianism has been an indelible feature of politics. But critics called it an unnatural alliance, doomed from the beginning. The government, meanwhile, mocked it as a tempest in a teapot stirred up by a “clique of the corrupt” in an effort to escape accountability for their financial shenanigans.

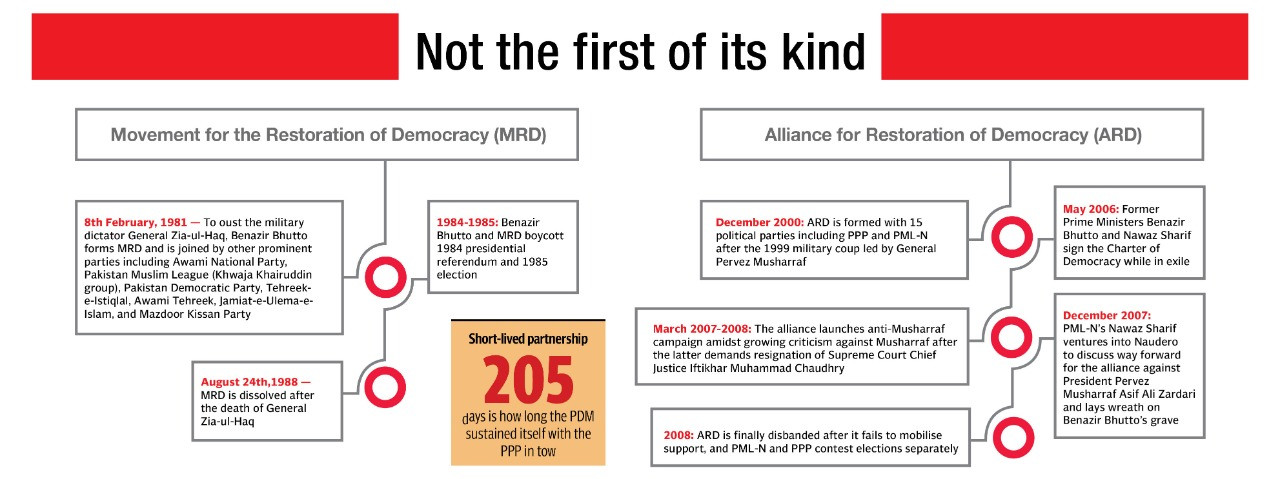

The PDM was not the first – and would not be the last – movement of its kind. It was the latest in a number of alliances cobbled up by political parties for the “restoration of real democracy” in a country mired in a chronic civil-military tug of war. The alliance was significant in more ways than one. Firstly, the PDM espoused a radical narrative of former three-time prime minister Nawaz Sharif, who is currently in London supposedly for the treatment of some undiagnosed illness. Sharif, who blames the military for his unceremonious exit from power, faults the miltablishment for the country’s current economic morass. And he believed the PDM could set off radical changes in the nature of the state by shifting the centre of power away from Rawalpindi.1618686800-22/WhatsApp-Image-2021-04-17-at-9-28-44-PM-(1)1618686800-22.jpeg)

Creative: Mohsin Alam

He unleashed frontal attacks on the establishment – sometimes naming the generals – in his virtual addresses at the PDM events. Such vitriol was unheard of in Pakistan’s politics. Hence it quickly hogged the media spotlight. These tirades were unprecedented especially because Sharif was himself a protégé of military dictator Gen Ziaul Haq. And the miltablishment consistently played him off against other political parties, especially the PPP.

Secondly, the PDM brought together almost all opposition parties – including bitter traditional rivals of the past, leaving Prime Minister Khan politically isolated. The coming together of the PPP and the PML-N made the alliance a potent threat for the embattled government. At the same time, the PDM also provided a national platform to peripheral nationalists from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan – who, chronically disillusioned by the state, have traditionally equated Punjab with the establishment – to speak to people in the heartland of Punjab. This inclusive alliance owed its birth partly to the political acumen of Maulana Fazlur Rehman and partly to the political naivety and narcissistic self-aggrandisement of Prime Minister Khan.

Thirdly, the PDM was virtually led by the PML-N, which has its bastion of power in Punjab, the home of the army brass and soldiery. This was the reason when Sharif amped up his anti-establishment rhetoric, Asif Ali Zardari took a dig at him: “My domicile doesn’t offer me such privilege.” And when Sharif explicitly accused two severing generals of “stealing” the 2018 elections in favour of the PTI, Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari quipped: “I’m sure Mian Sahib has credible evidence to back up his allegations.” Liberal political observers would agree that nationalist groups from smaller provinces are quickly demonised as “traitors” only for voicing their disillusionment with the state, let alone saying things that Sharif says.

Fourthly, the PDM generated a lot of political momentum with massive power shows in major cities of the country. Its promise to banish the establishment from politics fired up its supporters’ imaginations and projected the PDM as a genuine opposition. The sky-high inflation and exorbitant consumer prices resulting from a lack of governance and economic mismanagement won the PDM more popular support.

Meanwhile, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, who is driven by deep-seated loathing of Prime Minister Khan, did not let the alliance slack off. The PDM jalsas didn’t cause jitters, though government ministers would come out without fail to respond to the opposition’s criticism after every rally. The PDM demanded ouster of Prime Minister Khan. Their real target, however, were his military backers. Sharif and his political heir apparent Maryam Nawaz repeatedly said their struggle was not against the “selected prime minister” but against the “selector” – a not-so-veiled reference to the establishment.

The ruling party was convinced that internal contradictions would not allow the PDM to pose an existential threat to the government. So, it decided to let the alliance roll on and fizzle out. However, a shocking drubbing in the Senate elections threw the government off balance. Prime Minister Khan appeared clearly shaken during his televised address the next day. He decided to take a fresh vote of confidence from parliament to reassert his government’s legitimacy. The PDM relished its victory. Not for too long, though. Its leaders started squabbling publicly over the spoils. And the subsequent defeat of their candidate for Senate chairman’s slot triggered a blame game within the alliance as all component parties looked askance at each other. The defeat was particularly embarrassing because the alliance had clear numerical superiority in the house. And this is what led to the PDM’s “implosion”. But critics believe a number of factors led to the falling apart of the nascent alliance.

Firstly, the PDM was fraught with chronic distrust, especially between its two main component parties. The PPP and the PML-N had an unenviable political relationship in the past. And senior leaders from both parties made no secret of this mutual distrust. Khawaja Asif said in a televised talk-show that he was unable to “trust this gentleman, Asif Zardari”, even if he wanted to. Similarly, Aitzaz Ahsan would openly express his dislike for Nawaz Sharif who he derided as pathologically untrustworthy politician. While the PML-N and the JUI-F pushed for tearing down the whole system by resigning en masse from the assemblies before marching on the capital, the PPP did not agree. It had a lot at stake. Zardari wasn’t willing to give up his party’s government in Sindh, which has traditionally been the PPP’s political powerhouse. He knew that once out of power, it would be difficult for the PPP to win back Sindh, where the PTI has been making inroads. Zardari also knew that his party’s political survival hinges on its presence in power. The PPP flaunts the 18th constitutional amendment, which reversed a military ruler’s attempts to centralise power in the indirectly elected office of the presidency, as its achievement. The party fears the miltablishment wants to roll it back through the PTI government. The PPP knows that it could protect the 18th amendment only by staying within the assemblies.

Secondly, Sharif went on the offensive against the establishment like no mainstream politician ever did before. For the PPP, Sharif’s new narrative was too perilous to espouse. Sharif is full of bitterness for the miltablishment, which he blames for all his woes. And in the PDM, he found an ideal platform to settle personal score while championing the struggle for civilian supremacy. He went too far by directly accusing the army top brass for toppling his government and installing their “puppet” Imran Khan, through a “rigged election”. He earned a lot of brownie points, especially on social media, though some political analysts would call it a “political suicide bomb attack”. Sharif sought to sell his narrative to the entire PDM. He found willing buyers in the marginalised nationalist groups and the JUI-F, which has become so addicted to power that it would bring down the system it does not have a share in. The PPP saw Sharif using the PDM to hog the limelight. And it grew increasingly wary.

Thirdly, Maryam used the PDM as a springboard to catapult herself into the political limelight. Making the most of Shehbaz Sharif’s absence, she carried herself as the de facto president of the PML-N. She also rejigged the inner sanctum of the party and surrounded herself with a new coterie of hawks. Critics say she might be a good crowd-puller at public rallies, but she lacks political acumen, and her way of politics is crude and crass. Her struggle against Prime Minister Khan and his so-called “backers” appears to be driven more by personal vendetta than politics. She wouldn’t even listen to the voices of reason within her own party. And therein lies the rub. She is leading her father’s party into a dead-end street, assuming she hasn’t done that already.

Fourthly, a movement for the “restoration of real democracy” appears to be a joke in Pakistan. Or a ruse used by political parties when they are denied a share in power. In our country, democracy is still wedded to personality cults and political dynasties, which stymie the growth of a true democratic culture. The young scions and political heirs of these dynasties wouldn’t challenge the status quo while pursuing the interests of their old generations. And their parties would blindly follow them. “None of them is a Lenin, a Mao, a Che, or a Ho Chi Minh who can bring about a revolution. They are the kind of politicians who settle for a mere signal from the establishment that it would stay neutral in the power struggle,” popular columnist Wusat Ullah Khan once rightly said about Pakistani politicians in his talk show.

And lastly, the PDM had come together to oust the “puppet” government of Prime Minister Khan and send his “backers” back to the barracks. But it didn’t have a game plan for what it would do afterwards. The alliance cashed in on the “incompetence” of the government’s economic team, but it would not share how it would pull the country’s economy out of the current morass. The two major parties took the nationalist groups in tow, but they would not say how they would assuage their festering grievances and alleviate their sense of marginalisation, exclusion and alienation. While the alliance ostensibly campaigned for rule of law and supremacy of the Constitution, its politico-religious chief has a parochial worldview, which, I’m sure, would not be acceptable to a liberal and secular party like the PPP.

Some would suggest it is too early to write off the PDM. It might be down but not necessarily out. The exit of the PPP and the ANP has no doubt dented the alliance but has not unraveled it. Naysayers, however, say no matter how hard the Maulana and Sharif might try to resuscitate, the PDM is clinically dead. Prime Minister Khan must be happy to have survived a formidable challenge to his government midway into its tenure. He should be thanking his lucky stars. Khan shall consider it a new lease on life and deliver on his pre-election promises. Or else, he would need no PDM to spell doom for his political career.