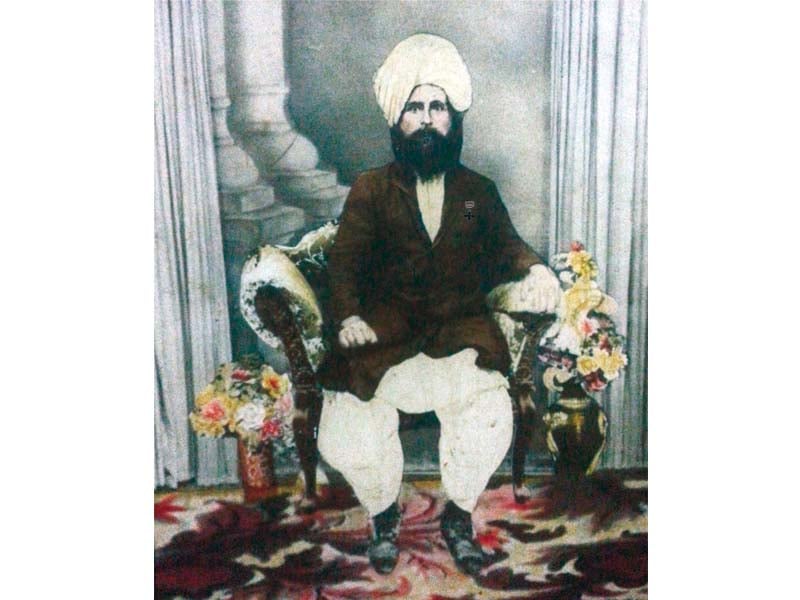

Ghulam Kadir Dayo was a man of towering political and social stature in Ratodero — a taluka in Larkana — which was once a stronghold of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s father, Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto. Dayo not only contributed to education, but also the maintenance of law and order, administrative writs of the government, access to government employment, and the recruitment of Sindhis to the royal army. He won the acclaim of the British Raj, and received titles like the chair holder of Commissioner Sindh — whose authority over the province equaled today’s chief minister — and bench magistrate. The police issued him Arfinnamas — appreciation certificates — for his assistance in maintaining law and order. He also received special acknowledgment letters from the commissioner for helping the police to solve two major cases of dacoities in 1902 and 1909.

In his book Land Lord Power and Rural Indebtedness in Colonial Sindh, historian David Chessman discusses this, saying, “The British administration introduced a special bench magistrate system to support good governance and writ of law. They were also recognised as chair holders or Kursi Nashin.”

To Dayo’s credit is the upbringing and education of one of the first two commissioned deputy collectors, Muhammad Ismail Kadri and Ghulam Mustafa Issani. Kadri, appointed deputy collector in the Imperial Services in 1923, was Dayo’s younger brother.

By 1913, Dayo was among the few enfranchised zamindars of Larkana who could elect a member to the Bombay Legislative Council, which had the status of an advisory body. After the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms in 1920, the number of seats grew further as three legislators were elected from Larkana alone.

Come 1923, Muhammad Ayub Khuhro, father of former Sindh education minister and historian Hameeda Khuhro, was elected to the Bombay Council from Larkana, along with Shahnawaz Bhutto and Karim Baksh Jato. Dayo and other landlords had Ayub Khuhro, who was a political opponent of Shahnawaz Bhutto, elected. This hinted at a political rivalry, which was brewing between the two families.

Hameeda Khuhro, who wrote her father’s biography, Muhammad Ayub Khuhro: A Life of Courage in Politics, mentioned the names of Wadero Sahid Khan Junejo, Syed Noor Muhammad Shah, Wadero Ghulam Kadir Dayo and a zamindar of Bakapur for supporting her father’s election.

Colonel (retd) Hassan Imam, grandson of Dayo, recalls his grandfather’s contributions to the communal harmony between Muslims and Hindus. He also supported the construction of schools and community centres for social upliftment. When World War I broke out, Dayo helped recruit 10 Sindhi soldiers to the Royal Army, besides making other monetary contributions. The Raj acknowledged his services through an Afrinnama.

“Coincidentally, the army opened a recruitment centre in Larkana (in 1999) in the same community centre which my grandfather had established almost a century ago,” says Imam.

He credits a family friend from Larkana, late Ghazanfar Ali Issani — a veteran of World War II who later served in the police force retiring as a DIG — for guiding him.

“He suggested that I should write to the army chief to open the [recruitment] centres in Larkana and other parts of Sindh as the soil was fertile and carries rich history of valour,” tells Imam of his January 1998 meeting with Issani. “I put forward this idea to the military command. It was accepted and I was posted as the first recruitment officer in Larkana.” During his tenure, around 20,000 soldiers were inducted from the Larkana centre, from 1999 to 2001.

“I witnessed the fading of the myth of rampant anti-army sentiments among Sindhis, watching tens of thousands of young men turning up to join the army.” Imam takes pride in his recruitment services because it makes him feel like he is following Dayo’s footsteps.

Leaving no trail behind

Despite his significant political and administrative services, Dayo’s mention from official documents — maintained by the British bureaucracy– and the history of Larkana’s 20th Century figures, remains either obliterated or omitted. Except for a handwritten description in an official logbook of Larkana detailing around 1,000 acres of land ownership of Dayo and his brothers in Ratodero, whatever is known about him is through the reminiscence of his heirs or some of the Raj’s issued certificates and accolades preserved by the family.

“The Raj maintained a detailed record about all the important persons specially those who served the government. It was called the blue book,” Imam explains.

During his tenure in Larkana, Imam combed all official records at the offices of the Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner, DIG and SSP of Larkana to ferret out any official account or description of his grandfather. To his dismay, he did not stumble across even a trace of Dayo.

“The pages containing the entire record from 1902 to 1927 from the blue book at Larkana’s collector [divisional commissioner] office appear torn apart. They are missing,” he claims.

“Issani told me that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto personally ordered the destruction of those records,” asserts Imam. The political rivalry between the Dayo clan and Shahnawaz Bhutto’s family was fueled because Dayo supported election candidates who opposed Bhutto in all the elections till 1937.

Renowned biographer Stanley Wolpert quotes profusely from the diaries of Shahnawaz Bhutto in his book Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan and found several references which point to the undeclared row between the two clans by citing Bhutto complaining that “a DSP Kadri annoyed him.”

“In those feudal times, the politics of our environment were essentially personal and tribal,” he wrote. Shahnawaz also held the “influential zamindars” responsible for poisoning his father Mir Murtaza Bhutto in 1899. From 1920 to 1934, Shahnawaz headed Larkana’s district board and chaired the city’s Central Cooperative Bank for several years. In 1930, he was knighted.

In 1937, Shaikh Abdul Majeed Sindhi who hailed from Thatta defeated Shahanawaz in the electoral contest over a seat in the Sindh Assembly with the support of tribal chiefs like Dayo himself. After his defeat, Shahnawaz left Larkana and shifted to Bombay and later Hyderabad Deccan in India, staying there until his death.

Imam subscribes to the idea of the strife between the two families and says there are various anecdotal accounts of clashes between them. He believes that ample reasons exist for attempts to wipe out his grandfather’s name from history.

The two clans also have varying accounts of who founded and established Ratodero in the middle of the 17th Century. Bhuttos credit their ancestor Sheto Khan and Wolpert, in his book, confirms this fact. According to the Dayos, their forefathers along with other tribes, and Hindu traders established it. However, the Imperial Gazetteer of India (V.21) states that Ratodero was formerly an encampment of a chief of the Jalbani tribe, Rato.

Dayo fell ill in late 1930s and died in 1942. His death effectively ended his political legacy as most of his kin joined public service and moved out of town.

Imam is in the process of writing a book about his predecessors, the places in Iran and Balochistan from where they migrated, and the tribes and history of Larkana.

“I want the history books in our part of the world to accord due recognition to my grandfather for his services to the people and the government in his time.”

Z Ali is a hyderabad-based reporter for The Express Tribune.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, October 18th, 2015.

COMMENTS (3)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ