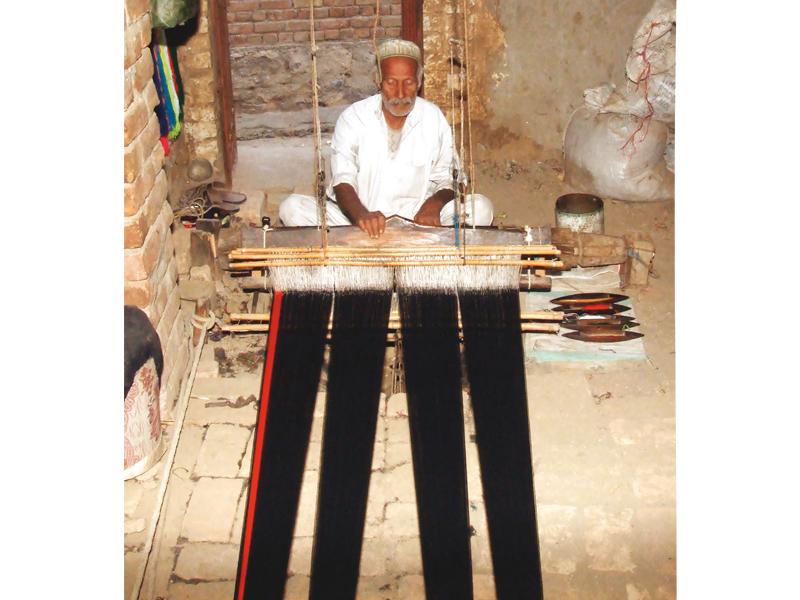

Local production of khaddar is long forgotten, but passion and tradition brave conditions to survive. PHOTOS : RASHID ALI

Khaddi or khaddar, a cloth primarily made out of hemp (high growing varieties of the cannabis plant and its products, which include fibre, oil and seed) is a combination of raw materials such as cotton, wool and silk, woven on a loom. The fabric owes its popularity to its versatility — warm in the winter and cool during the summer.

Though it is now mass produced in factories, older generations in Sheen Bagh are still working hard to keep the hand-made version of the fabric alive, despite meager earnings and high costs. While the newer generation is looking at more viable career options, this is the elders’ way of preserving their cherished craft.

Local production of khaddar is long forgotten, but passion and tradition brave conditions to survive. PHOTOS : RASHID ALI

To make khaddar, approximately 500 strings are passed through four combs, in a process that takes nearly eight hours of work a day, for three days straight. The khaddar sheet (a shawl, bed sheet or quilt) which is a result of the 24-hour labour process is then sold to local merchants for approximately Rs1,500.

In the retail market, the prices are quickly doubled. Khaddar sheets are sold for nearly Rs3,000 to Rs4,000, with little or no profit margin for the labourers. The minimal earnings have made the line of work unfeasible for many families in the village and it is no surprise that only four people have stayed true to their skill. These few professionals still weave cloth under the broken roofs of their houses with the same vigour that they inherited from their elders, nearly 80 years ago.

Baba Ahmed Khan, a resident of the village sits in his partially damaged home in one of the narrowest lanes of the area, “I was a young man, nearly 17 or 18, when I started working on a khaddi. From when Pakistan was founded, till now, I still work on khaddi — without my glasses.” Not one to abandon his craft, he considers the chargha, ricch, naal (components of the handloom) and the combs as his obedient friends. Baba Khan’s devotion to his skill is praiseworthy in a time when financial gains trump the satisfaction of completing a handmade product.

Local production of khaddar is long forgotten, but passion and tradition brave conditions to survive. PHOTOS : RASHID ALI

Cities like Peshawar and Multan are not foreign to the fabric and its skill, according to Baba Khan, “People from Multan invite us to work on special projects.” However, there is no change in the profits offered. “Merchants and companies make thousands of rupees off my products by selling them in cities like Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad and foreign countries. On the other hand, I can’t even procure a Rs100,000 loan for myself to buy enough material to last the year.”

Local production of khaddar is long forgotten, but passion and tradition brave conditions to survive. PHOTOS : RASHID ALI

Craftsmen like Baba Khan long for recognition and start-up capital but without local and international exhibitions, their growth in the industry is stunted. Lack of support and low profit margins aside, there are other factors contributing to the death of handlooms. In a story published in The Express Tribune, Aziz Khan, a power loom owner in Matta, Swat said that there are two types of loom — hand and power. Back in the day, hand looms were converted into power looms but since the process has become mechanised, power looms have become more common. However, Aziz added that the trend fluctuates due to prolonged power shortages.

If institutional support in the form of loans and direct access to markets is not provided, the craft faces a real danger of dying out with Baba Khan’s generation and the joy of wearing a hand-made khaddi kurta may soon become a thing of the past.

Local production of khaddar is long forgotten, but passion and tradition brave conditions to survive. PHOTOS : RASHID ALI

HOW THE LOOM WORKS

In a typical khaddi, there are four combs and four paddles to work with which are dug into a ditch. It’s almost like an orchestra, with each component strumming, coordinating and working with the other.

While running one comb with a hand, the worker sitting at the khaddi station moves one paddle with his foot simultaneously, allowing for the vertical threads (tana) and horizontal threads (bana) to weave together. The process looks simple enough, but it can be tricky as the threads can get easily tangled.

It takes five hundred strings in 13 or 14 knots to make a perfectly smooth shawl. The length of the woven fabric is nearly six metres, which is then cut into two pieces for sewing together. Women, who live near these handlooms, come and collect the sheets when done and add ‘tilla’ (a web of crisscrossed threads at the border) on both sides for a fee of Rs50.

Rashid Ali is an Attock-based correspondent for Roznama Express. He can be reached at attock72@gmail.com

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, December 22nd, 2013.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ