Out of the many realisations that the Covid-19 pandemic left us with, perhaps the most unsparing was the fear of isolation- something that we, as social beings, still struggle to come to terms with. However, what was the source of our greatest fear, was also what became, for many, their greatest strength in these hallowing times.

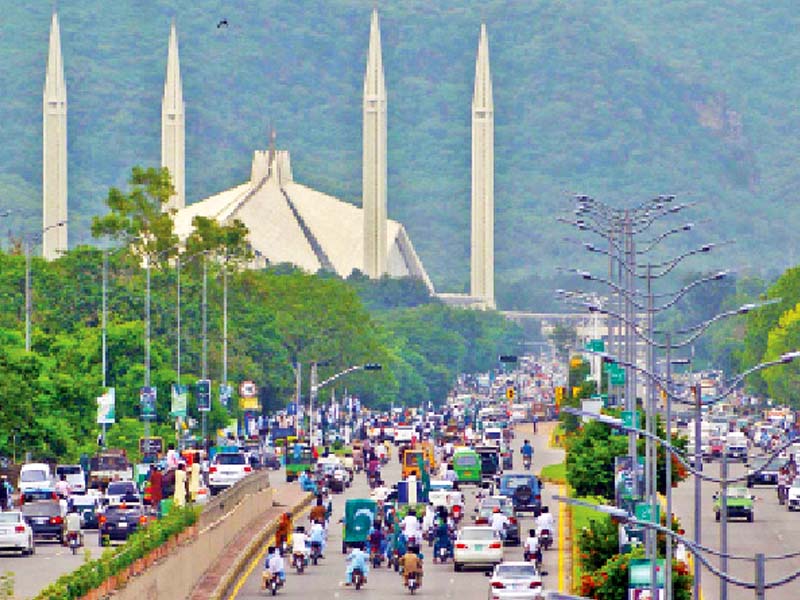

In the fast-paced, smoke-filled, chaos-hurling urban metropolis of Karachi, where much of life appears to pivot towards individuality; in a rather every-man-for-himself sort of way, community and family has also been the core of sustenance.

“I saw a lot of people in turmoil, and quite frankly I would have been no different, if it wasn’t for the support of my family,” recalled Haji Sultan Akbar. “We thankfully live in a joint-family system, so when times get tough, we are there to support each other. Had I been the only bread winner, things would have been much worse for us,” he added.

Pakistan, like other south Asian countries, had held the family system dear for many a decades, preserving the joint-family arrangement even when it started to frazzle out in the west and later in the east. Yet however, the post-90s saw a rapid increase in the trend of nuclear family structure, that consists of two parents and children as opposed to the joint-family structure consisting of two or more adult members; mostly extended family members such as cousins, aunts or uncles, grandparents and grandchildren living together in the same home.

In essence of Akbar’s experience, it is widely believed that joint-family structures are more likely to be financially stable, even in times of hardship, in contrast to nuclear arrangements where all responsibilities fall one or two breadwinners.

Speaking in the same vain, Begum Muqaddas, a matriarch who shares a five-bedroom apartment in the city’s Liaquatabad area with her four sons and their families, believes that a joint-family structure is more efficient than a nuclear unit. Quoting her own example, she said, “Look, I have four sons who all work in different companies. Two of them have better-paying jobs, while the other two work on a daily wage. All of them are married and have their own children. Since we share all our financial burden, even my sons who work on a daily wage never have to struggle for bare necessities.”

As the matriarch, Begum Muqaddas makes the family’s monthly budget, where each son hands her 60 per cent of their income, which she uses to pay for grocery, utility bills and other miscellaneous household expenditures. “The remaining 40 per cent of the income is what my sons keep for themselves. They use that to pay for their children’s education, health and other affairs,” she added.

Rida Shoaib, a housewife who had chosen to move out of the joint-family system and set up her own nuclear unit, believes that the post-pandemic inflation has made it impossible to sustain a nuclear family, with a single breadwinner on a minimum paygrade. “My husband makes Rs25,000 working for a private company, out of which over Rs10,000 go towards rent and utility bills. With what remains, it becomes really difficult to make ends meet and raise our two-year old daughter,” lamented Shoaib. “So we have decided to move back with our father-in-law. At least that would reduce some of our expenses,” she added.

Similarly, Parveen Kausar, an elderly widow whose husband left her a four-bedroom apartment, said that her two sons, both of whom are married, had never opposed living under the same roof. “However, it was only recently that my youngest son started to consider setting up his own apartment. He started budgeting and soon realised that it was not a very cost-effective decision to make and dropped the idea,” she told, stressing on the effectiveness of the extended family system, and how it’s the perfect alternative for the current economy.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 28th, 2021.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ