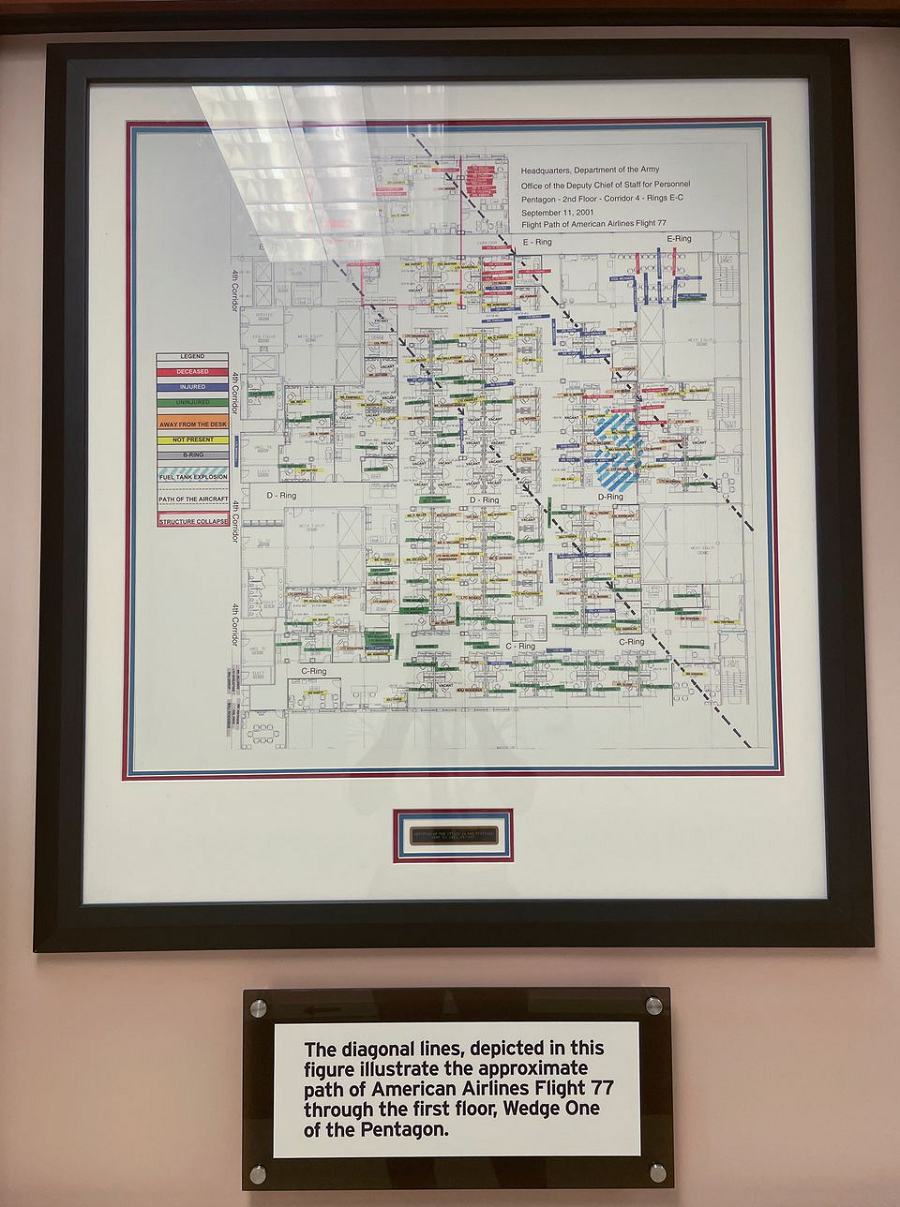

On the second floor of the Pentagon, a small map marks the path that a hijacked American Airlines plane took before hitting the military headquarters on Sept 11 2001, an attack that propelled the US-led invasion of Afghanistan.

A few corridors over hangs a full wall-sized poster of a 2009 Time magazine cover, with the words "How not to lose in Afghanistan" and an image of a US soldier smoking a cigarette somewhere in the country.

The building near Washington that houses offices for more than 20,000 service members and civilian defence employees, is littered with reminders of 20 years of US involvement in Afghanistan, America's longest war.

Was it all worth it? - That's a question senior military leaders are grappling with following the collapse of the US-trained and funded Afghan military, the Taliban's shockingly rapid takeover, a bungled evacuation of civilians from Kabul and the prospect of Afghans who helped Americans in the war being left behind to face reprisals from the Taliban in power.

"We see videos and photos, we read stories that bring back memories for some of us, and it becomes intensely personal," General David Berger, the commandant of the Marine Corps, wrote in a memo to Marines.

"Was it worth it? Yes. Does it still hurt? Yes," Berger wrote.

'Didn’t have to end like this’

It is common for service members to form bonds with the countries they deploy to, especially in combat.

There was deep frustration among service members deployed to Syria when then-president Donald Trump in December 2018 abruptly announced the withdrawal of 2,000 troops who had largely defeated Islamic State (ISIS). The move was criticised by officers and lawmakers as abandonment of Kurdish allies and leaving unchecked Russia and Iran's influence in Syria.

But unlike Syria, a generation of service members were shaped by Afghanistan, a war at first intended to oust the Taliban and target al Qaeda militants there who planned the attacks on New York and Washington.

Over the years, 800,000 Americans deployed to Afghanistan as the mission developed into a nation-building exercise. Nearly 2,400 were killed and more than 20,000 injured.

To critics, the US military was part of the problem. Senior military leaders have often presented overly-optimistic views. US airstrikes and raids killed women and children.

As intelligence reports started trickling in two weeks ago that the Taliban were sweeping through the country with little resistance by the Afghan forces, Pentagon officials said they were shocked.

When President Joe Biden gave a speech in which he said some at-risk Afghans did not want to leave, there was anger over his perceived lack of empathy.

In the past few days, there has been frustration over the slow pace of the evacuations of US citizens and vulnerable Afghans.

US military officials said they were unable to hold back tears during the past week.

For some, it was reading reports about the bases they lived in being overrun. For others it was receiving messages from Afghans, begging for help and warning that the Taliban would kill them.

"I want to be very clear: your service was not in vain, and it made a difference," Admiral Mike Gilday, the chief of US Naval operations, said in his own memo last week.

Aides to US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, who both served in Afghanistan, included references to the range of emotions service members were feeling when they spoke to reporters.

Both said they understood that the events in Afghanistan were personal for service members and these were difficult times.

"It was going to end sometime. It just didn't have to end like this," one military official said.

1732354127-0/Untitled-design-(3)1732354127-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ