The year 2019 has been a bumpy one for Pakistan, with the country entering another International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan programme and making some extremely tough decisions in a bid to boost the economy.

As part of negotiations for the 22nd IMF bailout package, the global lender demanded that Pakistan adopt a free-float exchange rate regime. Hence, after decades of being strictly controlled by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the government consented to put in place a market-based flexible exchange rate system.

Under the new regime, which came into effect in May 2019 onwards, market forces determine the value of the rupee against the dollar with the central bank intervening only in case of wide speculations.

It was a drastic shift and a much-needed one after the currency had been artificially held at a fixed value for around four years. During his tenure as finance minister, Ishaq Dar had opted to keep the rupee at a fixed rate against the US dollar.

Gold hits five-month high on escalating global tensions

Owing to this rigid control of the currency, it was unable to find its real value and as a result, the country witnessed massive rounds of devaluation later. Had the rupee been allowed to shed value in a gradual manner, businesses would have been better placed to deal with the shocks they received today.

So far, as things stand, the high interest rate and soaring inflation have translated into an overall slowdown in the economy. Though this slowdown is not exclusive to Pakistan and has been felt in many countries around the world, the choppy currency market in the past year certainly played a role.

"Devaluation is one of the key reasons for the economic slowdown. When the currency depreciates, your imports become expensive and you pass the impact on to consumers," said Alpha Beta Core CEO Khurram Schehzad.

He said the weakening currency impacted the consumers' purchasing power as devaluation fuelled inflation.

"With devaluation, there is inflation, when there is inflation, your disposable income goes down, which affects consumption behaviour and spending power. There is a decline in aggregate demand, which is why there is [an economic] slowdown," he added.

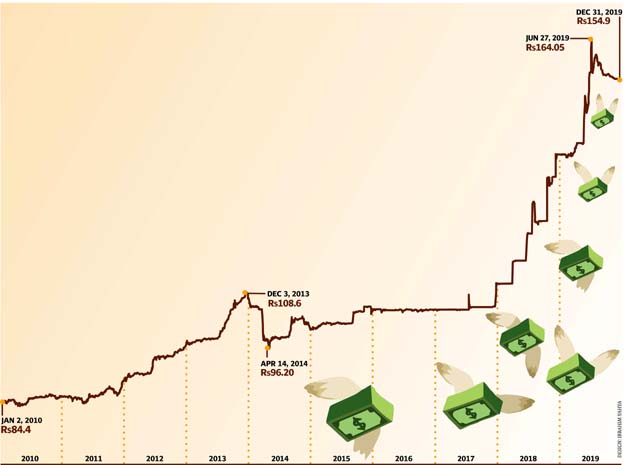

As Pakistan transitioned to a market-determined exchange rate, 2019 saw the rupee sustain a plunge of nearly 12% against the US dollar.

June 2019 proved to be particularly volatile as the rupee plummeted to a historic low of 164.04 against the US dollar. The free fall came after the government allowed market forces to determine the parity. Moreover, a widening gap between demand and supply also added to the pressure on the rupee.

Outflows on account of foreign payments and debt servicing pushed the foreign exchange reserves held by the SBP to $7.3 billion on June 28.

Despite this, the currency fared better compared to the jolts felt in 2018, when the rupee lost a record 32% (from December 2017) of its value against the dollar.

Explaining the reason behind the significant drop in the currency, economist Dr Shahid Hasan Siddiqui said the devaluation was linked with demand and supply.

"How much inflows are coming into Pakistan and what is the outflow. If we have fewer dollars and greater outflow, then the currency will feel the pressure," he added.

Pakistan has always been an economy that relied heavily on debt and imports, both of which lead to a hefty dollar outflow. Hence, managing the demand and supply situation is a challenge and the trend of the past decade is an indication that the country has been stuck in this loop.

At the beginning of 2010, the rupee was valued at 84.39, currently, it stands at 154.9, depreciating by a colossal 84% in the 10-year period.

Commenting on this, Arif Habib Limited (AHL) Head of Research Samiullah Tariq said, "A big reason for this [84% devaluation] is that our growth is driven by domestic consumption. Our savings are low and exports have lagged behind the broader economy."

He cited the mounting current account deficit and the lagging manufacturing sector as reasons behind the weakening currency.

He said 84% devaluation in a period of 10 years was quite significant and was mostly caused by structural problems. "Real issues were a declining manufacturing sector, low productivity, low investment-to-GDP and savings-to-GDP ratios."

He said the exchange rate trend of the past 12 years did not completely reflect the mess in the economy. "Our debt has grown three times but the economy has not grown in the same way."

Here is what happened

When the rupee was kept at a fixed rate, the exports became stagnant, however, inflation during that period remained under control. But in order to maintain control over the rupee, the then government had to borrow massively, which led to a towering pile of debt.

"We have borrowed massively in the past 10 years but despite the increasing amount of debt, the currency has depreciated substantially," Tariq remarked. "Since the NFC [award] happened in 2011, we lost our fiscal discipline and as a result the fiscal deficit remained consistently high, which caused a massive hike in the external debt."

Following this, Pakistan's debt-to-GDP ratio increased and the economy became consumption-oriented.

So, when Pakistan finalised the deal with the IMF this year, the rupee devaluation was not the only extreme measure it took, the central bank also raised the interest rate to an eight-year high at 13.25%.

"When the interest rate went up, businesses that were expanding found taking loans expensive, aggregate demand went down because the purchasing power dropped, which was why businesses were also squeezed," commented Schehzad.

In 2011, Pakistan's exports managed to fetch a record $25 billion. "We have not even managed to reach the highest level seen in 2011. We have a massive trade deficit, which created pressure on the rupee," Siddiqui added.

Highlighting the reason for the slow growth in exports, he said the high cost of doing business made the exporters unable to compete at the global level. "Our labour productivity is low and we don't have any surplus to export."

Explaining further, NUST Business School Dean Dr Ashfaque Hasan Khan said, "Our export-oriented industry has a high content of imported inputs, which is over 60%. When there is devaluation, the cost of all the imported inputs increases, which means that we are no longer competitive in the international market.

"To deal with this, we have to once again devalue the currency because we are not competitive."

He said in such scenarios "when we go to the IMF, it asks the government to further devalue the currency because the country is not competitive. So, this [boom and bust] cycle has always continued."

However, the current account deficit is not the only front that has contributed to the weakening rupee. Outflows stemming from debt repayments and interest payments have also mounted the pressure on the currency.

"There are structural issues, which led to massive depreciation," said the AHL official. Over the years, remittances from overseas Pakistanis have been a great boon for the economy as they played a key role in boosting reserves and lending some support to the currency. "Remittances have supported us a lot. If we minus those from the current account, then we are nowhere," Tariq added.

How it affects us?

Besides being a key part of the macroeconomic indicators, the rupee-dollar parity is very important for the common man. It is because of the massive weakening of the rupee that the country is facing double-digit inflation.

To understand how the parity affects the common man, it is important to note that Pakistan is a net importer. Since it imports more and exports less, and also has less investment, this means more outflows.

To counter this issue, "There should be import substitution. We should explore big commodities locally so that we can become self-reliant and reduce the burden on the common man," suggested Schehzad.

On the other hand, foreign investors are also directly affected by the fluctuation in the currency.

For instance, if an investor brings $100 in Pakistan and the exchange rate is Rs100 per dollar, then he will invest Rs10,000. If the rupee depreciates to Rs200 against a dollar, then the invested amount will increase in rupee terms but in terms of dollar, there will be no gain for the investor.

"Depreciation of the local currency leads to more risks for the international investors. Because the returns for them in dollar terms will decrease," Schehzad pointed out.

Hence, a stable exchange rate is not only vital for individuals but also for investors.

Following the debacle in June, the currency has managed to recover by a handsome 5.5% or Rs9.01 to Rs155.03. This was largely due to improvement in the current account deficit, which dropped 73% to $1.82 billion in first five months (Jul-Nov) of the current fiscal year.

Additionally, foreign currency reserves held by the central bank shot up to a 19-month high at $10.9 billion due to inflows from multilateral lenders. Hot money flows from foreign investors also helped improve the situation.

Outlook

Although most analysts are not expecting any sharp movement in the rupee by the middle of next year, they are of the opinion that the intrinsic issues need to be addressed to come out of this cycle once and for all.

Samiullah Tariq said governance and structural issues needed to be addressed, adding that the government should improve the tax-to-GDP ratio and focus on documentation of the economy.

"There is a need to improve the domestic sector productivity, otherwise there is no way out of this boom and bust cycle," he added.

Govt likely to introduce dollar-based saving scheme

He was of the view that if these structural issues are not addressed, "we will be back where we started from". He said the government needed to attract foreign investment in productive areas and skill-based sectors.

Talking about the future trend, he said, "Our expectation is that the rupee will weaken Rs2-3 by June 2020 and by December 2020 it will be Rs160."

Siddiqui dismissed any chance of rupee depreciation in the ongoing financial year, adding, however, that the rupee would not become cheaper as the country had received hefty inflows from the Asian Development Bank and China.

"There is not likely to be any major change in the currency value until June 2020. There may be a difference of a few rupees but not more."

Published in The Express Tribune, January 4th, 2020.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

1719053250-0/BeFunky-collage-(5)1719053250-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ