Ecuador's 'Pablo Escobar' drug kingpin extradited to US

Escobar was killed on a rooftop shootout in Medellin on December 2, 1993 - one day after his 44th birthday and five months after he appeared on Forbes magazine's list of the world's richest people for the seventh straight time. His eight-story mansion, the Monaco, a symbol of the decadent opulence of the Colombian mafia in the 80s and 90s, has fallen into disrepair in the years since his death.

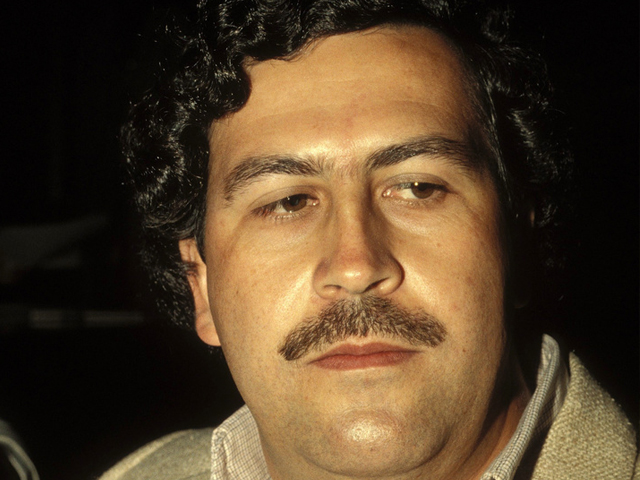

PHOTO: BUSINESS INSIDER

PHOTO: BUSINESS INSIDERIts battered frame still bears the scars of Colombia's first car bombing, in 1988, the start of a bloody war between the country's rival cartels.

The hulking white building is slated to be demolished in February, in a public implosion complete with stands for viewers to watch.

"The Monaco has become an anti-symbol, in a place where some people are outspoken defenders of crime and terrorism," says Manuel Villa, the city hall secretary who will perform the official countdown to the detonation. "We don't want any more children saying they want to be Pablo Escobar when they grow up."

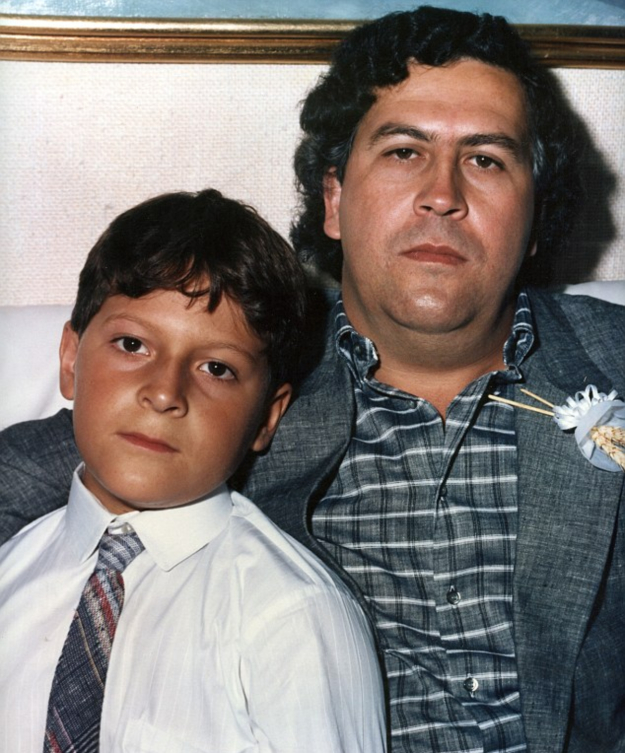

PHOTO: DAILY MAIL

PHOTO: DAILY MAILThe mansion, a top tourist attraction in Medellin's upscale El Poblado neighborhood, will be replaced by a public park dedicated to the thousands of people killed in Colombia by "narcoterrorism" - the no-holds-barred war the cartels waged on each other and the state in the 80s and '90s. The park will cost an estimated $2.5 million.

Renovating and reinforcing the crumbling mansion would have cost $11 million, according to the city. "It will be painful" to tear it down, says Villa, "but it's the only way we can heal our wounds."

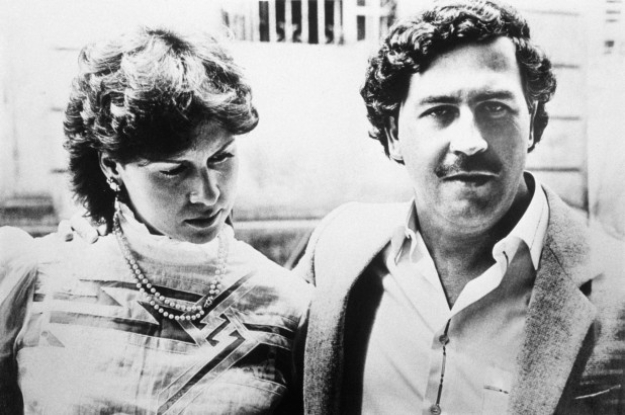

PHOTO: NEW YORK POST

PHOTO: NEW YORK POSTColombian society remains deeply divided over the legacy of Escobar and other drug barons. Angela Zuluaga is one of those who wants to wipe out the country's lingering "narco culture." She was an unborn baby in her mother's womb when Escobar's hitmen assassinated her father, a judge, for issuing an arrest warrant against their boss. Her mother was wounded in the October 1986 attack.

"Creating a space to remember the victims means having a space where we attempt to symbolically compensate those of us who have suffered from the scourge of narcoterrorism," she says.

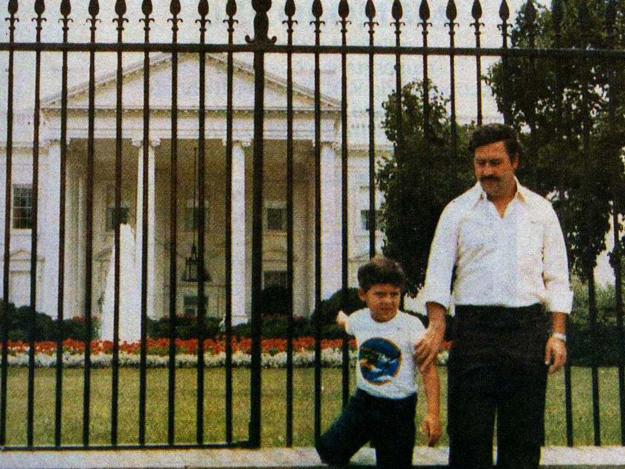

PHOTO: REDDIT

PHOTO: REDDITAccording to Medellin officials, Colombia's drug violence killed 46,612 people from 1983 to 1994. On the other side of this cultural divide, Luz Maria Escobar is changing the tombstone at her brother's grave ahead of the anniversary of his death, as a crowd of tourists looks on. Tearfully, she reads the new inscription, "Beyond the legend you symbolise today, few know the true essence of your life."

Moved, a young woman from Puerto Rico asks if she can give her a hug. Luz Maria acknowledges her brother made mistakes, but opposes the city's plan to get rid of his home. "Tearing down the Monaco isn't going to demolish Pablo's history," she says.

PHOTO: SKY NEWS

PHOTO: SKY NEWSEscobar is remembered as the "Colombian Robin Hood" in the neighborhood that bears his name, where he donated 443 houses to formerly homeless people who lived and scavenged at the local dump.

"I see him like a second God," says one resident, Maria Eugenia Castano, 44, as she lights a candle at an altar that bears Escobar's photograph. "To me, God is first, and then him."

Pablo Escobar's brother has some advice for makers of Narcos

At the nearby El Patron beauty salon, which sells, along with haircuts, a plethora of merchandise stamped with Escobar's image, stylist Yamile Zapata sums up the contradictions of the late cocaine king's memory. "Pablo will confuse you," she says. "If you want to look at the good side, he was very good. If you want to look at the bad, he was very bad."

Have something to add to the story? Share in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ