The book has a hidden, nuanced language of its own and Reddy has written it with such precision that one never grows tired of delving into such territory.

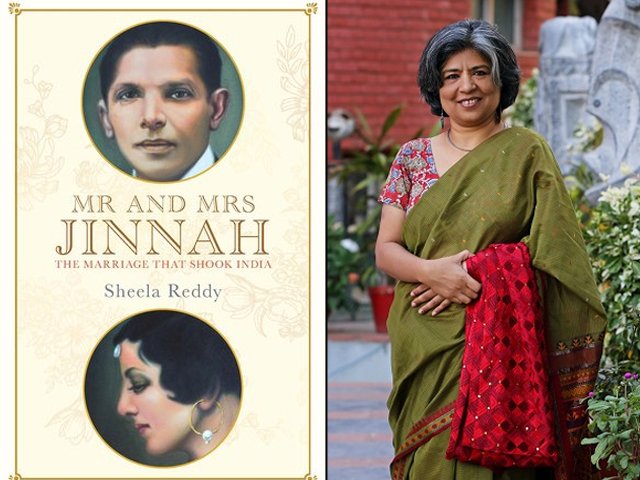

Mr and Mrs Jinnah: A story of love that wasn’t enough to save an ill-fated marriage

Their different temperaments & interests all troubled Ruttie to the extent that she developed an unlikely persona.

For the masses of the subcontinent (India and Pakistan), Sheela Reddy’s Mr and Mrs Jinnah tells the fascinating tale of a small yet poignant romance that some people might experience in life (if fortunate enough). The book explores some of the most vivid details of the lives of Rattanbai Jinnah (Ruttie) and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Jinnah’s political stalwart for projecting his career above communal rights, and the doomed marriage that ended in separation despite the unusual love that lived on.

Colonialism and the pre-Partition history of the subcontinent still enthrall the minds of both the old and the young. Since the populations of both India and Pakistan consist of mostly young people, the book offers the beautiful yet tragic story of Ruttie and Jinnah, who got married despite their age and religious differences.

As much as nationalism and jingoistic realities shake up the mantle and core of the global citizen in the present age, 1920s Bombay, despite colonialism and burgeoning communal and class realities, was still a very charming place; this is what Reddy’s book chronicles.

Largely centred on correspondences that are mostly of and related to Ruttie (she fervently enjoyed writing letters while Jinnah did not, and loved poetry and read Oscar Wilde), it was especially this that captured Jinnah’s heart and thawed his cold demeanour (for her).

However, as the book moves on and picks up pace, the reader becomes sad as Jinnah and Ruttie’s marriage soon starts floundering. Their different temperaments, different interests (only two in common – horses and motor vehicles), Jinnah’s unnatural attention and attitude towards politics, and his reserved method of dealing with problems, all troubled Ruttie to the extent that she developed an unlikely persona which was only a superficial covering of makeup and clothes over her bohemian and liberal personality.

The book carefully seeps the likes, passions and lives of both Ruttie and Jinnah through the mind of the reader, borrowing excerpts from the letters between Ruttie and Sarojini Naidu (Indian poet) and her two daughters, Padmaja Naidu and Leilamani Naidu.

As subcontinental history piques the interest of so many around the globe, the romance that Bombay found itself submerged in during the 1920s is an expression often lost when we try to read up something remotely related to the lives of our leaders. Considered almost or absolutely blasphemous, Jinnah’s personal life has never been narrated with so much subtlety and detail. Jinnah’s own temperament described in the book as “this medley of wild excitement and cold depression” leaves the reader not sentimental but quiet when one finishes reading it.

The book has a hidden, nuanced language of its own, and Reddy has written it with such precision that one never grows tired of delving into such territory. The book also charts some impressions, such as showing how Jinnah single-handedly manages to bring forth a brand of the Muslim man who is secular in almost all respects. Reddy also carefully shows Fatima Jinnah’s personality and her influence on her brother – the idea that Jinnah becomes a better Muslim after Ruttie’s death due to Fatima’s influence.

Reddy’s attempt to establish and bring forth the unusual but envied tale of Ruttie and Jinnah – her being ostracised from the community and Jinnah supporting her liberal and extravagant attire and expenditure – is an accomplished task of making them seem human. Often, as a curious Pakistani, there never really has been enough material to read on Jinnah’s life. This need has wonderfully been fulfilled by Reddy’s finesse on the subject.

The book does not present a date and time record. Instead, it builds its case by making both Ruttie and Jinnah seem more human to a population that despite 71 years of history does not know its leader well. Interestingly, the book shatters the myth that it was Ruttie who loved cats and dogs (and Jinnah did not quite share this liking) by revealing that after Ruttie’s death, Jinnah too developed a liking for them.

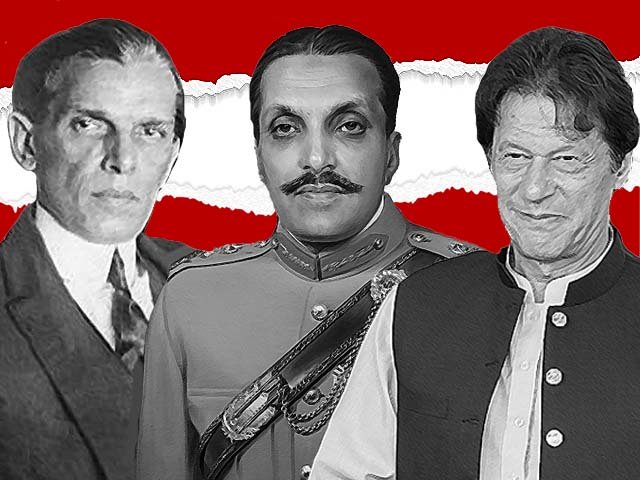

Reddy’s book provides us with details of the political and communal realities of an India that was beginning to see the crevices that started to appear due to communal differences imposed by the British Raj. By providing an inside glimpse into the life of Jinnah, it functions as a biographical note to establish his character and his ambition in the subcontinental political scene of the early 1920s.

Since our local textbooks or other sources hardly even give an elusive reference to his family, siblings, personal life or his overall struggle (managing to build his position as an influential politician of the subcontinent), the book provides a detailed look into Jinnah’s demeanour, personal life and personality.

Throughout the book, the reader finds words spoken or written by the characters, but because of Jinnah’s cold and quiet approach, we do not see him expressing much. Although the book at times does feel a little like a strand from the elitist spectrum of 20th century British India, it still manages to keep an honest voice by reserving its judgment on the characters, and letting us form an opinion of our own.

1617734258-0/Cover-(3)1617734258-0.jpg)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ