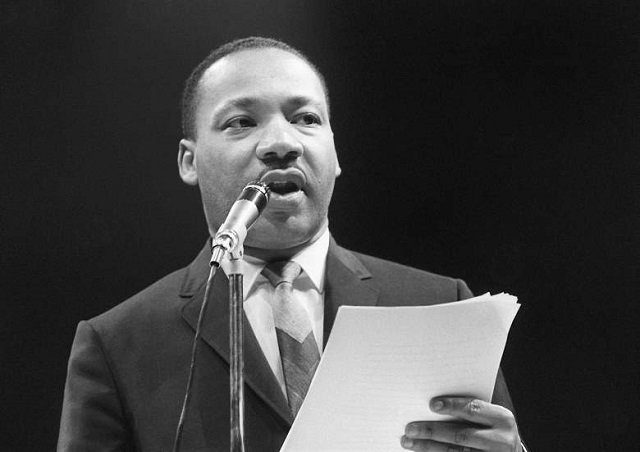

The domes, the intricate tile work, the floral and scripted patterns of the shrine all are testament to the creative genius of the tombs’ designers. PHOTO: FLICKR/SMDANISH

The city of Sufism, saints and nirvana – Multan has more to offer than you think

Call it arrogance, ignorance, or innocence, but coming from Karachi, I genuinely did not expect much from Multan.

Earlier this year, I took a trip to Multan that was meant to be an official excursion, and yet somehow proved to be a bit of a life changer. As I waited to board my flight, I “checked in” on my Facebook account, and in turn was presented various sites referencing Multan as the “City of Saints”.

All I knew about Multan was that it was famous for its blue pottery and other textile items, which is why this revelation made me feel excited at the prospect of my trip to the city.

Coming from Karachi, I genuinely did not expect much from Multan. Call it arrogance, ignorance, or innocence, but I had absolutely no idea what awaited me. Thus, disembarking at the Multan airport was the start of many surprises to come. The airport itself is quite small, but is unbelievably clean, and if you ignore the land coverage, it is truly comparable to its counterparts across the country.

Upon leaving the airport, I realised that when my colleagues described Multan as a small city, they were not kidding. I was due to visit two branches as part of my official trip, and it took less than seven minutes to reach the first location from the airport.

The trip was not a long one by any means – my return flight was scheduled for 8:00pm the same day. However, as I completed my official agenda within working hours, my cab driver calculated I had almost two hours till I had to make my way to the airport, and suggested he show me around his city. As we made our way, he gave me a historical prelude to the sites he wanted to show me.

I discovered Multan, Pakistan’s fifth-largest city, was a kingdom mentioned in the Mahabharata, conquered by Alexander the Great, called Darul Aman during Emperor Akbar’s time, and recognised as the birthplace of Baba Farid, the first Punjabi poet.

On our way, we crossed the Ghanta Ghar (literally translated to clock tower) and the Hussain Agahi Bazaar. This is Multan’s oldest bazaar, indicating the antiquity of the city. The streets were dotted with eateries offering a variety of edibles, ranging from barbeque items, fish, sweets and savoury items. It feels as if Multan could easily pass off as a foodies’ paradise, given the chance.

A short drive ahead, we made our way to the outskirts of the city, and stopped to see its famed pottery works. Multan is known for its “Kashi” (blue) pottery works. This craft is influenced by Persian, Central Asian and Mongolian art, and its origin can be traced to the city of Kashgar, in western China. Each piece is handcrafted and hand-painted before being treated with heat, and the resulting product, though very delicate, is also remarkably durable. Each piece maintains its colour and condition, even if exposed to the harshest of natural elements, for well over 100 years.

Legend dictates Multan is Pakistan’s mystical heartland, and visiting the city is considered a spiritual journey for the pilgrim. After all, each of the likes of Bahauddin Zakariya, Shams Tabrizi and Multan’s glory, Shah Rukn-e-Alam, has a shrine in the city in their honour.

Though I managed to get a fleeting view of each shrine, I made it a point to visit that of Rukn-e-Alam. Having never visited a shrine before, I was not aware of the protocols, if any, which needed to be followed. To be fair, one cannot really gauge any prerequisites whatsoever from outside of the tomb, which is why you need to go in and find out on your own. In your first visit, like it was for me, it takes a while to overcome the grandeur of the external architecture of the mazaar and step inside. The domes, the intricate tile work, the floral and scripted patterns, all are testament to the creative genius of the tombs’ designers.

Overcoming my initial awe and entering the tomb, I was transported to an entirely different world altogether. Decorated with lines of colourful lariyaan (flower strings), it was all unbelievably surreal.

Taking a moment to close my eyes, I felt an indescribable calm wash over me. I realised there was no protocol at all – you just had to be. Everyone else was simply doing what they wanted to. Some devotees slept on the shrine floor, some chanted a kalaam I couldn’t really understand, while others just stood praying near the grave.

There were small white structures around the main grave, which I was later told were graves of Rukn-e-Alams’ devotees. Upon my enquiry, I was informed these people were buried vertically; hence the small size of the graves.

Right outside the tomb area is a “mannat-kadda”, which is a large sized lantern with “diyas” lit inside. A local man pointed out that for my prayers to actually be heard, I would have to place some money in the ledge beneath the mannat-kadda. Not sure how reliable this advice is.

Nonetheless, the time I spent at this shrine gave me a new perspective on life in general. What does shrine culture represent to devotees who visit shrines across Pakistan? Is it just for nomads who count on getting a meal or two for free? Or is it about experiencing personal peace? Maybe there are those who have complete faith in the divine healing powers of the Sufis, or use these Sufis as a “waseela” (intercessor) to their prayers. Who knows?

I do believe, however, that depending on the intensity of each visitor’s faith, these shrines provide an opportunity to attain absolute nirvana.

In that moment – as I peacefully stood at Rukn-e-Alam’s tomb – I realised how, in dealing with the small stuff, I often miss the bigger picture. Looking at these devotees pursuing what they believed in, as they prayed and chanted kalaam, they seemed to connect with something bigger than themselves.

And this, perhaps, is what Maulana Jalaludin Rumi meant when he said,

“Let yourself be silently drawn by the stronger pull of what you really love.”

All photos: Sarah Fazli

COMMENTS (7)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ