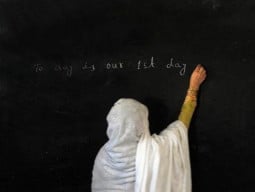

With the nation celebrating its 68th Independence Day as a moment of joy, the occasion also provides us with an opportunity to think about the vision and the objective of creating the new state of Pakistan. The vision that pulled the diverse Muslim communities from different regions of British India together in demanding and finally winning an independent homeland in the Muslim majority areas of the subcontinent became subject to many conflicting interpretations. This was not unusual though. Every post-colonial state has been through this process. In contrast to Pakistan, however, other comparable states were able to resolve the question of what kind of state and society they wanted their country to be. They did it through the agency of a nationalist party, charismatic leadership and political institutions.

Pakistan found itself in too much of a deficit in every quality that could keep the country on track for achieving the vision that the founders had outlined, most notably Mohammad Ali Jinnah in his August 11, 1947 speech in the Constituent Assembly. There cannot be any other authentic account of the vision of Pakistan than this address of Jinnah at the premier institution that had before it the dual tasks of writing a new constitution and also legislating to deal with a wide range of issues. The importance of this speech also lies in the fact that it was Jinnah’s first speech as the president of the Assembly. The speech touches on a diversity of subjects, from the importance of a law-based society to corruption and nepotism, termed “poison” to highlighting the challenges of poverty, equality and communal harmony. The essence of this remarkable speech, however, lies in three very modern ideas of state and nationhood.

First, there would be equal citizenship rights for every one regardless of religion, ethnicity and caste. What Jinnah meant by this formulation was the territorial conception of citizenship, discounting religious affiliations. Second, territorial citizenship will dissolve the differences and make Hindus, Muslims and communities of other faiths equal in rights and obligations. Finally, religion was a private matter of the individual, and the state had nothing to do with it. In other words, what Jinnah visualised was neutrality of the state in religious matters, a concept that is essential for internal peace and stability.

These are some of the Enlightenment ideas many post-colonial leaders, including Jinnah, liberally borrowed from Western civilisation. Jinnah was a constitutionalist in his training, profession and practical politics. It is unfortunate that every school of thought and political strand have attempted to interpret Jinnah to sell their own specific brand of politics and ideology. This is always true when it comes to great leaders in history because their popularity carries a heavy weight of argument on the side of conflicting political brands.

Pakistan lost track of Jinnah’s path even before it could walk any significant distance on it. The influence of mullahs, the weakening of Jinnah’s successors and the disintegration of the spirit of Pakistan brought into prominence leaders and political forces that had nothing to do with the founder’s vision. In less than a decade, bureaucratic-military leaders captured the state apparatus and reduced Jinnah merely to a symbolic portrait to hang behind their desks in offices.

No wonder, then, that the destiny of Pakistan over the decades has become disputed. The religious right demands an Islamic state, simply to capture power in the name of religion and do the same things the ‘moderate’ parties and leaders do. The ruling political establishment of Pakistan has used power as an opportunity to rob and run, leaving behind nothing but chaos, disorder, and finally, extremism and terrorism.

Pakistan can recover its lost vision. For this to happen, it will have to bring the corrupt, thoughtless political establishment within the bounds of law and accountability. That will be the new beginning.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 12th, 2015.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS (17)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ