No.

What does a young population want? Opportunities. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realise that our state pays much more heed to wars in foreign countries and has not really thought things through when it comes to its exploding population and the accompanying youth bulge. Not only do we forget to create opportunities for our youth, we are not even bothered about their skill enhancement in order to make them more productive citizens.

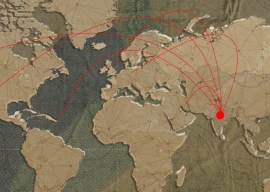

Recently, I had an opportunity to attend a group meeting with a senior executive of one of our largest private school systems. Among other things on the agenda, one item being considered was the inclusion of a foreign language in the curriculum for all classes in addition to English. I was taken aback to see the school management and parents almost agreeing on the unlikely choice of languages. Was it Chinese, Spanish or Portuguese? No sir, it was Arabic. Now I know Arabic is the fifth most spoken language in the world unlike the first four. But Chinese, Hindi, English and Spanish, which are common in the countries and regions that are considered engines of growth (China, India and Latin America), the oil-rich Arab world where this language is spoken seems to be a sinking ship. Given that this is an investment in our children’s future, say, 16 years down the line, do you think the rapidly changing energy market the Arab world will be able to retain its pivotal position? And special efforts to intellectually migrate to the Middle East notwithstanding, can we forget that most radical influences, such as those of outfits like al Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS), have reached us from the same route? As for the quality of the scholarship in the language, you really need to read the UNDP’s 2002 Arab Human Development Report which points out three deficits in Arab countries, namely the freedom deficit, the women’s empowerment deficit and surprise, surprise, the human capabilities/knowledge deficit relative to income.

Coming back to the present-day troubles that we face, one has to talk about two of our own deficits: one of reliable and verifiable data. All our population numbers seem to have been plucked out of thin air for in the absence of a population census, all you have are projections. The second deficit is that of opportunities. We do a poor job in educating our youth relative to income generation. My favourite point, which I didn’t let successive chairmen of the Higher Education Commission forget, is that in an age when an aspiring writer can earn a decent living by learning creative English writing, we are still teaching our children how to critique works of Pope and Chaucer in English literature. We don’t teach them to create, invent or innovate and when they still do, they find out our patent office exists merely in some godforsaken virtual reality approachable only to the inventors of virtual reality. The situation would not have been so bad if we had a plan for job creation in the private sector. But you know what’s happening there. Another excellent idea was to offer soft loans for start-ups. Sadly the best bid in this case, the PM’s youth business loan scheme, was unfairly targeted by opposition leaders such as Imran Khan just because it was headed by the prime minister’s daughter. That criticism was unfair to this ambitious scheme and the young lady’s hard work.

It appears that we can only agree on how to radicalise the youth; not on how to de-radicalise it. Perhaps, then, teaching our children to speak in fluent Arabic is not such a bad idea. They can always find employment within the IS camp.

Additional reading: A Future for the Young — Options for helping Middle Eastern Youth Escape the Trap of Radicalization by Cheryl Benard, September 2005, RAND’s Initiative on Middle Eastern Youth.

Published in The Express Tribune, March 14th, 2015.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS (7)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ