The first thing that strikes you is the poverty and not just in the shape of the old refugees from Palestine and new ones from Syria. Buildings stand half built. My friend points to a couple of high-rises that seem to go up 40 floors. He says construction was abandoned about 10 years ago as architects had forgotten to design a sewage system for the towers.

The city does not seem planned in the academic sense. Much like Karachi, roundabouts or ‘circles’ as they are referred to locally, serve as geographical reference points.

USAID stamps assert themselves on most plaques at tourist attractions. Expats tell me that the US has pumped huge sums of aid into Jordan. Research tells me that after Afghanistan and Pakistan, the third highest amount of American aid goes to Jordan.

The Umayyad Monemental Gateway to the palace on the Citadel hill in Amman. PHOTO: MYRA KHAN

“Jordanians are confused about the US,” says an American. “On the one hand they are giving Jordanians all this money, and on the other hand they’re starting all the wars in the Middle East.” It makes it hard for them to form a single opinion about the US.

I can relate.

Feeling cheated

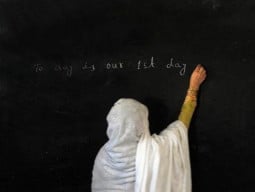

I started feeling cheated by pictures of Queen Rania. Jordan might not be the powerful, liberal country its representatives make it out to be. The litmus test was the way women were perceived.

In the souks for every 20 men, I see only one woman. In Jordan, by the age of 24 you are assumed to be married, friends tell me. Women, foreign women more perhaps, are hassled by the young men. In most cases, they shout haram, bandying it about unlike how we do in Pakistan.

I can’t say that the women are more conservative because I saw a lot of local Jordanians who were not. There are women who were the hijab and those who don’t. It’s perhaps evidence of natural diversity within a religion or culture, but I expected more respect from the men. The officer giving me a visa on entry asked why my head was not covered if I came from a Muslim family.

Hadrian’s Arch in Jerash built in 129 AD. PHOTO: MYRA KHAN

The scene

Restaurants are buzzing in Amman, especially if you walk downhill from the first and second circles. Jordanians enjoy going out, smoking sheesha amid bites of hummus and muttabal. The food is divine. It is safe to say all those falafel places I ate at while studying in England were doing it wrong. Jordanians also enjoy a good barbeque. They don’t skimp on the meat.

The sights

Speaking in broken Arabic, only using words such as yanni and taqreeban, I take a taxi to one of the best viewpoints — the Citadel.

It is in this spot that the Roman Temple of Hercules stands next to the Byzantine church and the Umayyad mosque alongside an Early Bronze Age cave. You even walk through a broken Ammonite palace.

Rub a dub dub

The session at the hamam proved to be one of the highlights of my trip. Before you go, ensure you are extremely comfortable with your body. They will ask you to wear nothing but your underwear. Don’t worry, it’s segregated. If you feel uncomfortable, I suggest closing your eyes, because the women who work there don’t take no for an answer.

Remains of the Temple of Hercules, dedicated to the deity and constructed between 161-166 AD. PHOTO: MYRA KHAN

You are first shoved into a steaming sauna that blinds you temporarily. In the midst of your yelps of pain an arm pops through the plastic curtain and hands you a pomegranate juice slushy. Savour this till the end.

After the sauna, another sweltering experience awaits in the jacuzzi. After your pores are opened, you lie on a marble slab where you are scrubbed to remove the grime. After they exfoliate the top three layers of your epidermis it’s off to the massage and then to a wooden coal steam room.

Jerash

At these ruins I saw the grandest, largest display of Roman architecture I could possibly lay eyes on at a single site. It had everything I studied in history class — the arches, the hippodrome for horses and chariots, the central plaza encircled by pillars, the fountains.

Walls of the city of Petra laced with tombs that have fallen victim to earthquakes and erosion. PHOTO: MYRA KHAN

The most spectacular part was being able to walk in the grooves that chariot trails left behind centuries ago.

Petra

There’s a public transport strike for buses leaving Amman. At the time, rumours were circulating that three university students had been shot dead.

Finally on route to Petra, the journey seems bland. Flat desert and sporadic ghosts towns don sides of the roads.

Petra was first ‘sighted’ in 1812, by a Swedish man pretending to be a Muslim trader. Claims go as far back to 300 BC of when it was created. For centuries it remained unknown to the world outside. Bedouins, a nomadic people spread all over Arab world, inhabited the built-in-stone structures and lived here for years without telling non-natives of the existence of Petra.

The end of the entrance to Petra, As-Siq, is a narrow crevice, making it hard for people to discover the city in olden times. PHOTO: MYRA KHAN

You almost miss the narrow opening on the left that takes you into Petra. The entrance is so tall that it has its own name: As-Siq. It is over 1000m. A shallow groove in the wall shows a water irrigation system along the entire way in. The walls reach up to 80 metres in places as if the city wanted to keep itself a secret.

Most of the statues are damaged. Guides say much of Petra was hit by earthquakes in old times, but the dwellings remain. Many Bedouins still act as tour guides, giving camel and donkey rides.

Here, the ultimate destination is the Monastery. What you see along the way is forgotten up a grueling hike through sand, stones, stairs, with Bedouin women selling you their jewelry for almost any price. If you ignore them, they shout, “It’s the same way down!”

The monastery, like every other building, that been carved horizontally into a thick stone wall with stunning precision.

They say Petra was abandoned eventually as trade routes went elsewhere. I can’t imagine why, or how anyone could leave it behind.

Not far from the monastery are viewing points where you can look over the entire valley. A Bedouin says that there is a river with lush green trees below, and that I can see Syria from here.

“Syria? From the south of Jordan?” I ask.

“Yes,” he replies.

I only believe the first half of his sentence.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, May 19th, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook to stay informed and join the conversation.

COMMENTS (3)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

@Stranger:

Why are you scared? Jordan is one of the safer 'Muslim' contries

Nice article. wish I could go there. We are scared to go to any Muslim country now for hols . Please dont take this personally but hope you understand - our lives are more precious.

Loved the pictures and the bits of small information you casually give out with your easy writing style.