KARACHI:

In May 1994, the Presidential Advisory Council on Science & Technology reported to South Korean President Kim Young-sam that profits from the film Jurassic Park equaled the revenue generated by 1.5 million Hyundai cars that the country exported that year.

This is testament to how film, as a part of the creative industry, has the ability to surpass any other sector. And the distribution of funds is relatively democratic — your creative capabilities define your role. It enriches the society both materially and intellectually, promoting creativity and adding to the intellectual pool of the country that enhances our ability to create and present narratives.

Those who feel cinema is about just money and entertainment completely miss the point. Indian politician Shashi Tharoor once said, “Today, it is not the size of the army or of the economy that matters, but the country that tells the better story. Components of India’s soft power are … all successfully exported through Bollywood across the world.” Furthermore, Sally Totman notes in How Hollywood Projects Foreign Policy, “The association between the change in Libyan status in US foreign policy and the changing role of Libya in US films is significant.”

Rizwan AQ — Pakistan’s final cut pro

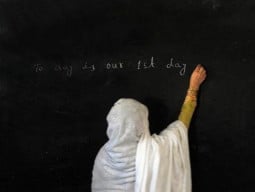

The greatest power in the world is the ability to influence the human mind. Film and television are prime mediums not only to reach out to the domestic population but also to international consumers. Countries use their media not just to maintain healthy discourse within their own societies but also to jealously guard themselves against foreign influence. Pakistan, unfortunately, does not rank among those countries. We have surrendered our population to foreign influence and destroyed our existing film and TV culture. Consequently, we are unable to present our narrative both at home and internationally.

These days, the rebirth of cinema in Pakistan is the talk of the town. We have 46 cinemas with 86 screens today as we aim at hitting an output target of 20 films per year. Back in the late 80s, we had roughly 750 cinemas and were churning out as many as 80 films a year. So, what exactly happened? Have we learnt anything from the past?

Hope is essential for all human endeavours. But being an analyst, I have this bad habit of asking questions. Is the current wave of a few overzealous producers, taking exorbitant risks with their time and money with an uncertainty of profits at hand, sustainable for the future? Is the growth of cinemas the same thing as the growth of the film industry? Do profits for cinema owners and distributors translate into profits for producers, actors and crew? Is the present revenue-sharing model between the producers, distributors and cinema owners optimal, equitable and sustainable? Is the cinema owner the industry’s lynchpin or the distributor or the film-maker?

Pakistani cinema will have an identity of its own: Imtiaz Ali

The film-maker is essentially the industry’s live wire — he is the first mover. Unfortunately, a lack of regulatory framework is killing the very film-maker. Despite putting in all the hard work, financial risks and conceiving an excellent product, the film-maker is unable to break even.

The revenue division equation is simple. 50% of the money generated by the tickets is retained by the cinema owner. Almost 30% is raked in by the distributor and the media partner and the remnant falls in the hands of the film-maker. It is pertinent to note that this 20% too is released bit by bit to the film-maker months after the film is out. Can an industry survive in a situation like this? Where does hope help in all this?

The national legislature needs to devise a policy framework at the earliest. Most countries of the world use protectionist policies to safeguard their film industries during nascent years. The requirement for regulation is imperative for more than one reason. Can Hollywood and Bollywood survive without their respective domestic markets? Should a film not have a certain degree of guaranteed access to the local market?

Clearing the smoke on ‘Maalik'

The policy needs to incorporate the following provisions:

1. All exhibitors in Pakistan must display Pakistani films for at least 130 days in a year.

2. At least 33% of the films distributed annually by every Pakistani distributor should be made in Pakistan.

3. A complete tax holiday on film income, including film services, distribution and exhibition for at least 10 years, for films made in Pakistan.

Untapped outreach

The Pakistani vernacular ranks as part of the world’s second most spoken language. This can benefit us immensely in terms of both revenue and outreach. Pakistani films have a potential market in several areas of the world, such as the Middle East, India, Europe and North America, where a significant number of people speak and understand Urdu/Hindi. In addition to helping the economy, our films can help us extend our influence and soft power.

The writer is a film-maker and actor best known for PTV drama serial Dhuwan (1993)

Published in The Express Tribune, December 14th, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS (6)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ